"An inside job" — Phrase of the Week

Allegations of decades-long theft of national treasures from Nanjing Museum

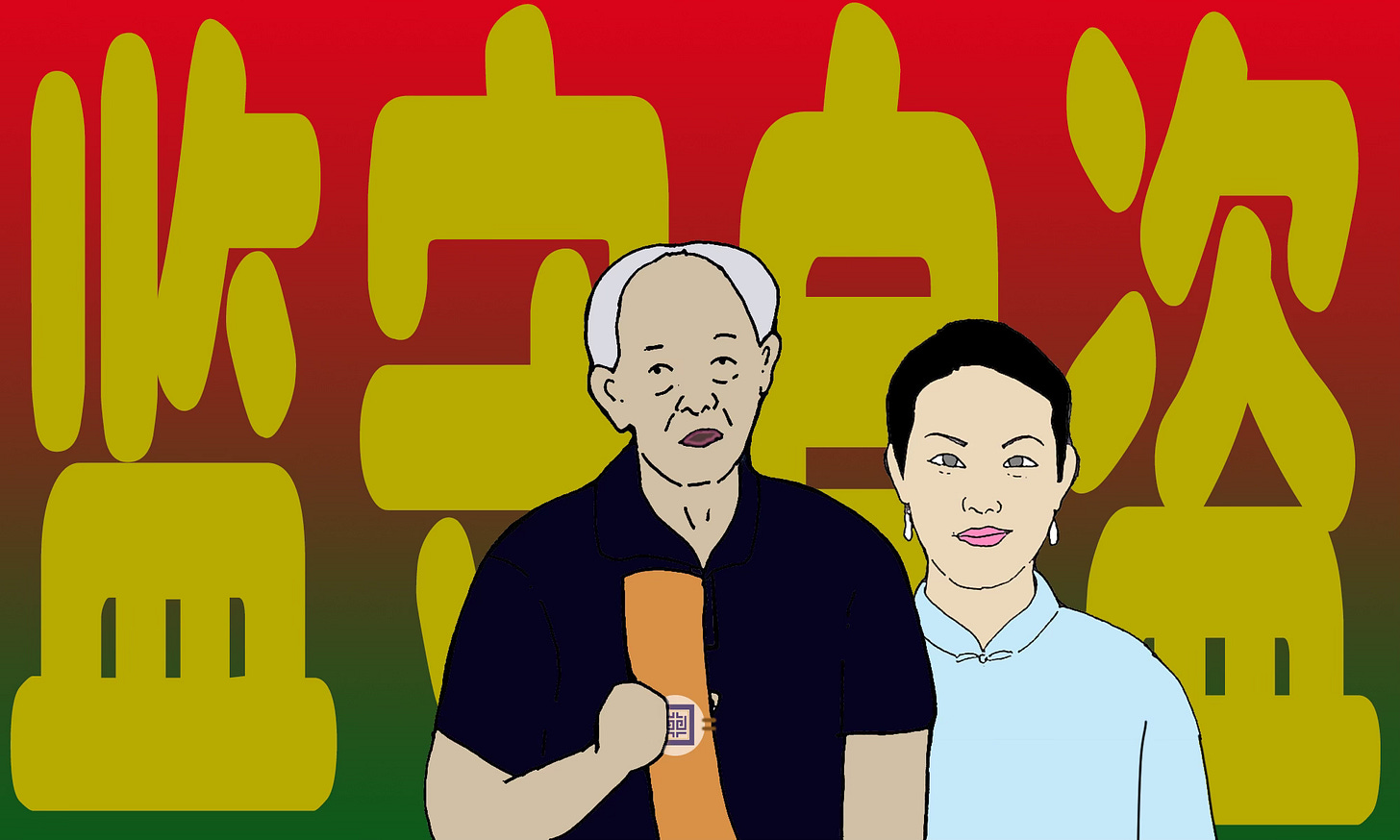

Our phrase of the week is: “An inside job” (监守自盗 jiān shǒu zì dào)

Context

The Nanjing Museum is at the centre of a major scandal involving missing national treasures, fake identities, and allegations of systematic theft spanning decades.

The story centres around Spring in Jiangnan (江南春), a painting by Ming master Qiu Ying (仇英), which appeared at a Beijing auction in June 2025 with an estimated price of 88 million yuan ($12.1 million USD).

That piece was one of 137 artworks donated to the Nanjing Museum by wealthy collector Pang Laichen’s (庞莱臣) family in 1959.

In late December, a whistleblower report alleged that former director Xu Huping (徐湖平) orchestrated the sale of thousands of valuable artefacts as fakes over decades, selling them at rock-bottom prices to a store he controlled, then reselling through his son’s Shanghai auction house at full price.

Records show Spring in Jiangnan was sold as a fake in 1997 for just 6,800 yuan.

As the scandal unfolded, another name emerged: Xu Ying (徐莺). Coincidentally sharing the same family name as Xu Huping, she has claimed to be a Pang family descendant since 2014, with the older Xu’s endorsement. Online commentary describes her as the “Miss Dong” (董小姐) of the museum world.

The story has struck a nerve in China, where large-scale theft of national treasures has always been a sensitive topic:

The online fury captures the mood of the era: beyond the loss of national treasures, it’s the sense of an inside job that shatters public trust when the supposed custodians steal what they’re meant to protect.

网友的愤怒,正是这个时代人们的心声。我们不容忍的,不是仅国宝流失,更是守护者监守自盗的信任崩塌。

And with that, we have our Sinica Phrase of the Week.

What it means

“An inside job” can also be translated as “theft by a custodian,” which is a classical Chinese idiom (监守自盗 jiān shǒu zì dào).

Literally, the four characters mean: “guard” (监 jiān), “watch over” (守 shǒu), “self” (自 zì), “steal” (盗 dào).

It describes when someone in a position of trust who steals the very thing they’re supposed to protect.

The earliest written record of this term appears in the Book of Han, Records on Criminal Law (汉书·刑法志), a historical text compiled in the 1st century CE during the Eastern Han Dynasty.

The relevant excerpt reads:

“Those who guard county official property yet steal from it themselves will be treated with utmost severity: regardless of prior sentencing or lesser punishments, they will be put to death publicly.”

守县官财物而即盗之。已论命复有笞罪者,皆弃市。

The most famous historical example comes from Han Dynasty official Tian Yannian (田延年), who served as Grand Minister of Agriculture around 70 BCE. While supervising construction of Emperor Zhao’s mausoleum, he requisitioned 30,000 ox-carts from civilians to transport materials.

Tian reported to the court that each cart cost 2,000 wen (文), copper coins used as currency in ancient China. His total reported budget was 60 million wen. But he actually paid cart owners only 1,000 wen per cart, which was half the reported price.

Tian embezzled the remaining 30 million wen in state funds, roughly equivalent to a small prefecture’s annual budget. When the case was exposed, Tian Yannian committed suicide.

So “theft by a custodian” implies large-scale, systematic corruption. It’s a serious allegation describing not just theft, but betrayal of trust.

In the Nanjing Museum scandal, this idiom captures exactly what sparked such fury online. National treasures were donated to the museum for preservation, but this former director allegedly sold them through family-controlled channels for personal gain.

In English, this might be translated as “embezzlement by a custodian” or “theft in office.”

But we prefer “an inside job” which captures the fundamental betrayal perfectly.

Andrew Methven is the author of RealTime Mandarin, a resource which helps you bridge the gap to real-world fluency in Mandarin, stay informed about China, and communicate with confidence—all through weekly immersion in real news. Subscribe for free here.