By Jitsiree Thongnoi

A group of Thais boarded the high-speed train between Boten and Vientiane, the capital of Laos. They had just finished a tour in China before crossing to the Boten station, about five minutes from the China-Laos checkpoint. The carriage was half empty because it was the last ride of the day.

“Will this train ever turn a profit when it is empty like this?” one of the travelers wondered. The train is by far the largest public infrastructure in Laos.

But soon after, the train became full of locals. The Thai travelers got curious and asked a young Lao girl who sat nearby why she was traveling at this hour.

“I have work in [the city of] Luang Prabang tomorrow,” the girl said.

It’s the train’s fourth year of operation. The railway has benefitted Lao people in many ways, even as debt concerns and the project’s ability to turn a profit remain.

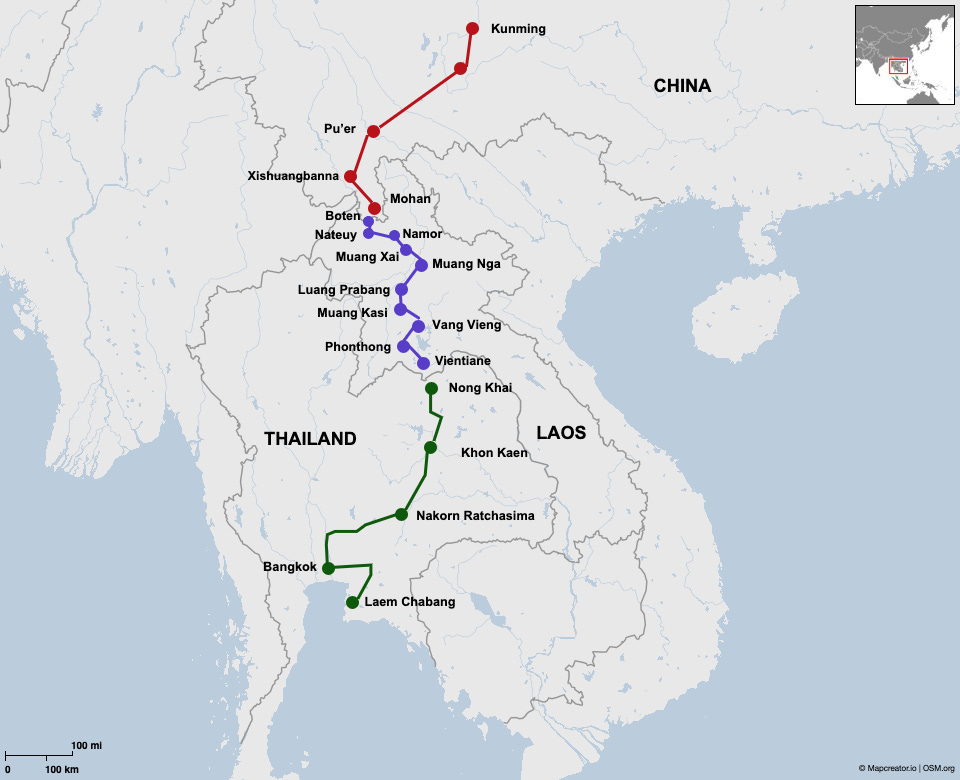

Part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Boten–Vientiane railway was jointly built by Laos and China. It connects Laos’ capital city, Vientiane, and the northern town of Boten. The total length is 414 kilometers.

The line’s north end is linked to the Chinese rail system in Yunnan Province through the Yuxi–Mohan railway. In the south, it will connect with the Bangkok–Nong Khai high-speed railway in Thailand and possibly all the way to Singapore.

BRI watcher and independent scholar Nick Freeman said the train’s popularity among Lao citizens was a ‘given’–as long as it was completed successfully and the cost of using it was reasonable.

Now, “…it’s time to start ensuring that Laos gains the greatest economic returns from its construction so that the economic returns derived match the significant investment made,” Freeman said.

The $6 billion project has been criticized because it puts more strain on Laos’ debts. China funds about 40% of the costs, while the rest is from the loans Laos took from the Chinese Exim Bank.

“[There is a] potential ‘debt distress,’” said Daniele Carminati, a visiting lecturer in international relations at Thailand’s Mahidol University International College.

But while he thought that the train would take a while to be profitable, he also believed that the economic boost deriving from surrounding activities like business, trade, or tourism would be significant enough.

“[The] sheer publicity in international media can lead to additional opportunities,” Carminati added.

A 2020 World Bank report predicted that the railway would generate income growth, higher income opportunities, and GDP growth for Laos. In June 2023, the Chinese Communist Party’s newspaper China Daily reported that the Laos section of the line had 2.5 million passenger trips since its opening, with up to 10,000 trips daily.

The train has increasingly become a crucial part of Lao people’s daily lives. Laos is the only landlocked country in Southeast Asia, yet it has one of the worst infrastructure regionally.

For 32-year-old Pok, traveling to Vientiane used to take her about seven hours. She is a cloth seller in Luang Prabang who often has to visit the capital to buy wholesale clothing for her business.

“Now it takes me two hours on the high-speed train,” Pok said.

It has boosted tourism, too.

Tui Somboon, a 42-year-old Luang Prabang-based tour guide, said the train has benefited his work. Since the start of February, which coincides with the Chinese New Year, he noticed that the number of Chinese tourists has risen. Most of them arrive in major cities of Laos on a high-speed train from Kunming in China.

“Chinese tourists used to fly to Laos from Xishuangbanna (an autonomous prefecture in China’s Yunnan province),” Tui said. “They also used to arrive at Luang Prabang from the Chinese border on buses, which took them around seven hours.”

Lady, a rookie tour guide from Vientiane who has been working for three months, said the high-speed train is the most important part of her job. “I use the train every day,” she said.

Laos has benefited from the train, Lady admitted. She thought it was a good form of transportation.

However, even as Southeast Asians’ preference for China increased, a degree of caution persisted. In the annual survey of the Singapore-based think tank ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, about 68% of Laos respondents said they were worried about China’s growing influence in the region.

For others, China’s economic presence in Laos is appealing. With the success of the high-speed rail, those opportunities are more within their reach.

Sociocultural Impact

The increased Chinese presence in Laos has encouraged youngsters to learn Mandarin, as they believe it will help them in the future.

Asi, who gave only his first name, is a 24-year-old man who works at a Chinese-owned entertainment venue in Vientiane. He said that if the train had not existed, he would have had to work in the field like many in his hometown, Muang Xay.

Now, he plans to study Mandarin and probably move to work in the Golden Triangle, where Myanmar, Thailand, and Laos converge on the banks of the Mekong, probably in a Chinese-run establishment there. Knowing how to read and write the language is important, he said.

Tip, a 21-year-old student in Luang Prabang, told CGSP she enrolled in a Mandarin language school last year. She believed there would be many more Chinese living in Laos later.

“It is not that we have to pay respect to China, but we have to learn about China and not act like an illiterate person in their presence,” Tip said.

Sociopolitically, the growing presence of Chinese people–whether tourists, businesspeople, or workers taking care of the railway operations and maintenance–will likely impact how Laos sees its relationship with China, according to Carminati, the Mahidol University lecturer.

“But it may be too early to say whether this is more positive,” he said.

Whether the train will bring true economic benefits for Laos remains to be seen, analysts said. Its success will depend on several other infrastructure projects, including a planned economic zone in Boten, the town where the Laos railway section begins.

Thai economist Aat Pisanwanich said the Belt and Road railway helped turn Boten into a city with the highest potential in the country. Its border with China means it can become a logistics gateway to ASEAN for China and vice versa.

“It might take about five years for the economic zone to take shape due to China’s and global economic downturn,” he said.

“It is not that we have to pay respect to China, but we have to learn about China and not act like an illiterate person in their presence.”

Tip, a young Lao student

Currently, Boten is only half built and has no tourist attractions, but that might soon change. At the economic zone exhibition hall, a short walk away from the Laos-China checkpoint, a city model maps out a vision of the future. There will be state-of-the-art freight checkpoints, high rises for international companies, resorts and hotels, and medical and wellness centers.

Pisanwanich was skeptical of the idea that the Lao people would directly gain from such economic development projects. This is because China already dominates almost all sectors in Laos. China is currently Laos’ biggest investor. Over 900 Chinese-funded projects across the country have a total value of US$13 billion.

“I’m afraid the country won’t gain much,” he said.

Meanwhile, the independent BRI watcher Nick Freeman said a key measure of the railway's success would be spillovers for people and businesses in Laos, whether through job creation or new business opportunities. Once the whole BRI railway is completed, Laos will also feel the positive impact more.

“Remember that China’s ‘long game’ is for the railway not to terminate in Vientiane,” Freeman said. “[The railway will] link up with the Thai railway system, and then further South to Malaysia and Singapore.”

Jitsiree Thongnoi is an independent journalist based in Bangkok, Thailand.