"Mr. Nan Guo" — Phrase of the Week

Trainee doctor "Miss Dong" accused of being a modern-day "Mr. Nan Guo"

Our phrase of the week is: "Mr. Nan Guo" (南郭先生 Nán Guō xiānsheng)

Context

One of China’s biggest healthcare scandals in recent memory has been unfolding in recent weeks.

It began at Beijing’s prestigious China-Japan Friendship Hospital, where thoracic surgeon Dr. Xiao Fei (肖飞) was exposed by his wife for having multiple affairs with colleagues.

His latest relationship with a trainee doctor named Dong Xiying (董袭莹) sparked the scandal.

Dr. Xiao was fired and expelled from the Communist Party. But as public attention grew, focus shifted from the affair to the background of “Miss Dong” (董小姐).

Dong is a resident trainee physician (规培生), who entered medicine through the “4+4 clinical medicine pilot program”—a fast-track path designed for students with non-medical degrees to complete medical training in just four years.

Originally intended to cultivate interdisciplinary talent, the “4+4” program is often used as a shortcut for the well-connected to land prestigious hospital placements and avoid years of standard training.

On Thursday, China’s Health Commission released findings of its investigation into Dong and Dr. Xiao. It confirmed Dong’s admission to the “4+4” program was fraudulent and noted suspicions that her path into medicine was smoothed through influential connections.

At the heart of the public backlash is a deep-rooted frustration in Chinese society of nepotism and abuse of privilege in China’s healthcare system—especially when it raises questions about patient safety:

“Ordinary people may tolerate unprofessional teams in the business world, but they will never accept a fraud like Mr. Nanguo in the operating room.”

老百姓可以接受商场里有草台班子,但绝不允许手术台上站着南郭先生

Lǎobǎixìng kěyǐ jiēshòu shāngchǎng lǐ yǒu cǎotái bānzi, dàn juébù yǔnxǔ shǒushùtái shàng zhànzhe Nán Guō Xiānsheng.

And with that, we have our Sinica Phrase of the Week.

What it means

The phrase “Mr. Nanguo” (南郭先生) is a common expression with a historical reference that anyone with an elementary school education in China knows.

It first appeared in the Book of Jin (晋书), the official dynastic history of the Jin period (265–420 AD). It was compiled during the Tang dynasty which began around 200 years after the fall of the Jin.

The reference to Mr. Nanguo appears in the chapter, Biography of Liu Shi (刘寔传):

“If the practice of promoting the worthy is not established, and the policy of indiscriminate appointments is not changed, then the court will be filled with men like Mr. Nanguo.”

推贤之风不立,滥举之法不改,则南郭先生之徒盈于朝矣。

Tuī xián zhī fēng bú lì, làn jǔ zhī fǎ bù gǎi, zé Nán Guō xiānsheng zhī tú yíng yú cháo yǐ.

Liu Shi (刘寔) was a respected official and Confucian scholar during the Western Jin dynasty, known for his integrity and criticism of declining moral standards in public life during the Jin period.

Here Liu warns of the dangers of poor personnel selection in the royal court by referencing a well-known fable from the Warring States era several centuries earlier—the story of Master Nan Guo (南郭先生), which satirizes the rise of unqualified officials who hide behind titles and appearances.

The tale goes like this: Emperor Xuan of Qi (齐宣王), a ruler during the Warring States period, loved the yu (竽), a traditional Chinese wind instrument. So he assembled a royal band of 300 yu players to perform in his palace. Those chosen were well paid and enjoyed a comfortable life.

On hearing this, a man named “Master Nan Guo” (南郭先生), who couldn’t actually play the instrument, tricked his way in by pretending to be a skilled musician. Hidden in the crowd of hundreds of players, he swayed along with the music, faking it without playing, while enjoying the benefits of being in the royal band.

His life of luxury came to an abrupt end when Emperor Xuan died and his son, Emperor Min of Qi (齐湣王), took the throne. Unlike his father, the young emperor enjoyed solo performances.

Knowing he would be exposed, Nan Guo fled.

In modern Chinese, “Mr. Nan Guo” has become a metaphor for people who fake qualifications or bluff their way into roles they are unfit for.

The story is particularly resonant in online discussions around the Dr. Xiao–Miss Dong scandal, where Miss Dong is accused of being a modern-day Mr. Nan Guo—bluffing her way into a medical training program through family connections, fraud, and the “4+4” shortcut.

Andrew Methven is the author of RealTime Mandarin, a resource which helps you bridge the gap to real-world fluency in Mandarin, stay informed about China, and communicate with confidence—all through weekly immersion in real news. Subscribe for free here.

Read more about how this story is being discussed in the Chinese media in this week’s RealTime Mandarin.

One final thing….

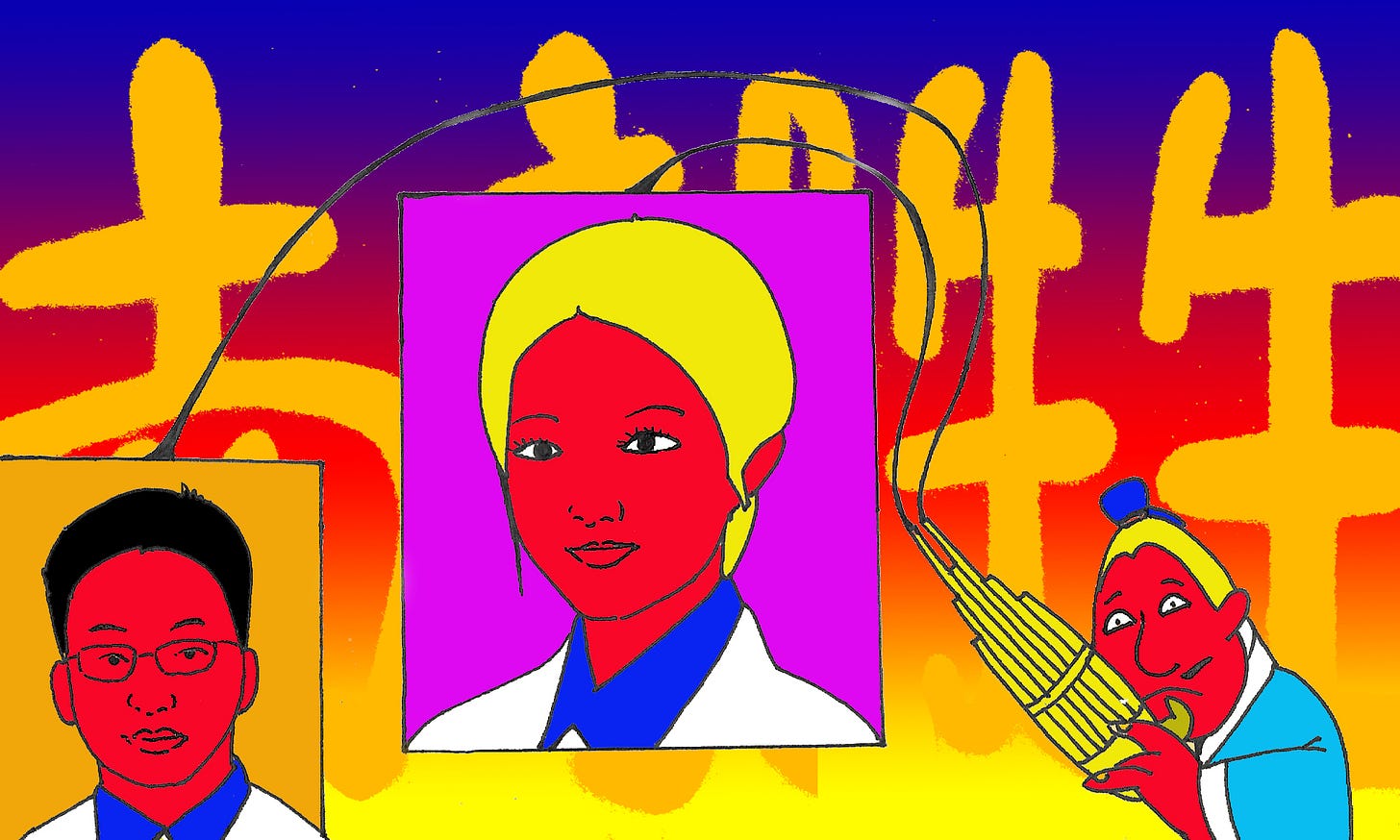

We’ve just started working with a new artist, Zhang Zhigang, to bring Phrase of the Week to life.

What do you think of this week’s artwork? Any constructive comments or words of encouragement?

Please let us know in the comments!