My China Priors, Part 2

Listen to my narration of this essay above. For Part 1, click here. Part 3 is here.

“Where you stand,” as Rufus Miles famously said, “depends on where you sit.” I set about writing this extended essay to offer readers a candid account of the various places I’ve sat as I’ve looked at China. Doubtless, some will simply say that it just confirms the prejudices they’ve long suspected I harbor. That’s fine: just don’t tell me that I’m unaware of them.

In my years in China, I was aware of the many privileges I enjoyed — aware, too of the salubrious effects of identifying them, just as I’m trying to do in these essays.

The first and greatest among these would have to be the years in China themselves. If you had to pick any span of 20 years in recent history as most conducive to a relatively optimistic perspective on China, you could do worse than 1996 to 2016, the years when I lived in Beijing continuously. The center decade of that, 2001 to 2011, was what many “China-watchers” have called the Golden Age, and with good reason: It was a period during which Chinese society was generally more tolerant, the government was less domestically repressive, foreign relations were relatively untroubled, the public sphere expanded dramatically due to the rapid spread of the internet, mobile phones, and later, the mobile internet, and culture flourished. There were downsides, of course: it would have been hard to miss the worsening air pollution or the growing social inequality. Less visibly, corruption certainly deepened. But the faith in better futures, the expanding personal freedoms, and the largely healthy pride Chinese people felt made it a great place to live: it was energizing because it was so dynamic, in a self-conscious moment of modern transformation that felt limitless. I said it then, in one of those many sequential years of double-digit GDP growth: “I’m lucky enough to have experienced directly in one lifetime the feeling of a rise in two great nations.”

If I had to pick one moment that sealed for me the sense of optimism, it would have to be the night of July 13, 2001, the night that the city that would host the 2008 Summer Olympics was to be announced. I was on the rooftop of a building at Jianwai Soho, then considered a swanky address, at a party thrown by the Beijing power couple of the day, Pan Shiyi and Zhang Xin. The first vote came in, and the city of Osaka was eliminated: That announcement prompted one Chinese guy standing near me to shout “Yè!“ 耶 which sent a ripple of laughter through the anxious crowd. When, on just the second ballot, Beijing was announced, it felt like the whole city erupted in a spontaneous cheer. Instinctively, somehow, everyone knew just what to do: We all converged on Tiananmen. Twelve years earlier people had done so in protest; now, many of those same people did in unembarrassed celebration. We let the good times roll. Random strangers hugged and high-fived all along the route. The party went on until the wee hours. It set the tone, for me at least, for the years to follow.

It’s obvious enough to anyone listening to the Sinica Podcast over the years that I’d love to see China return to times like those. Part of me understands the futility in that hope: The structural changes in the relationship between the U.S. and China, whether in their “comprehensive national power” or in the way their economies are no longer the complementary (or co-dependent) matched pair they were 20 years ago. But I remain convinced that an important part of what made that Golden Age possible was America’s post-9/11 distraction, which removed enough of the anxiety from China’s leaders that their hackles were down, they relaxed internal controls, opted for collective leadership, and focused on economic development. Countries are not just individuals writ large: I get that. Not entirely. But a lifetime of interaction with Chinese people has convinced me of the folly of the belief that China only responds to strength, to force. No: I’m confident that when it comes to China, we should take a page from the Daoists and practice a little wúwéi 无为. Less would get us more.

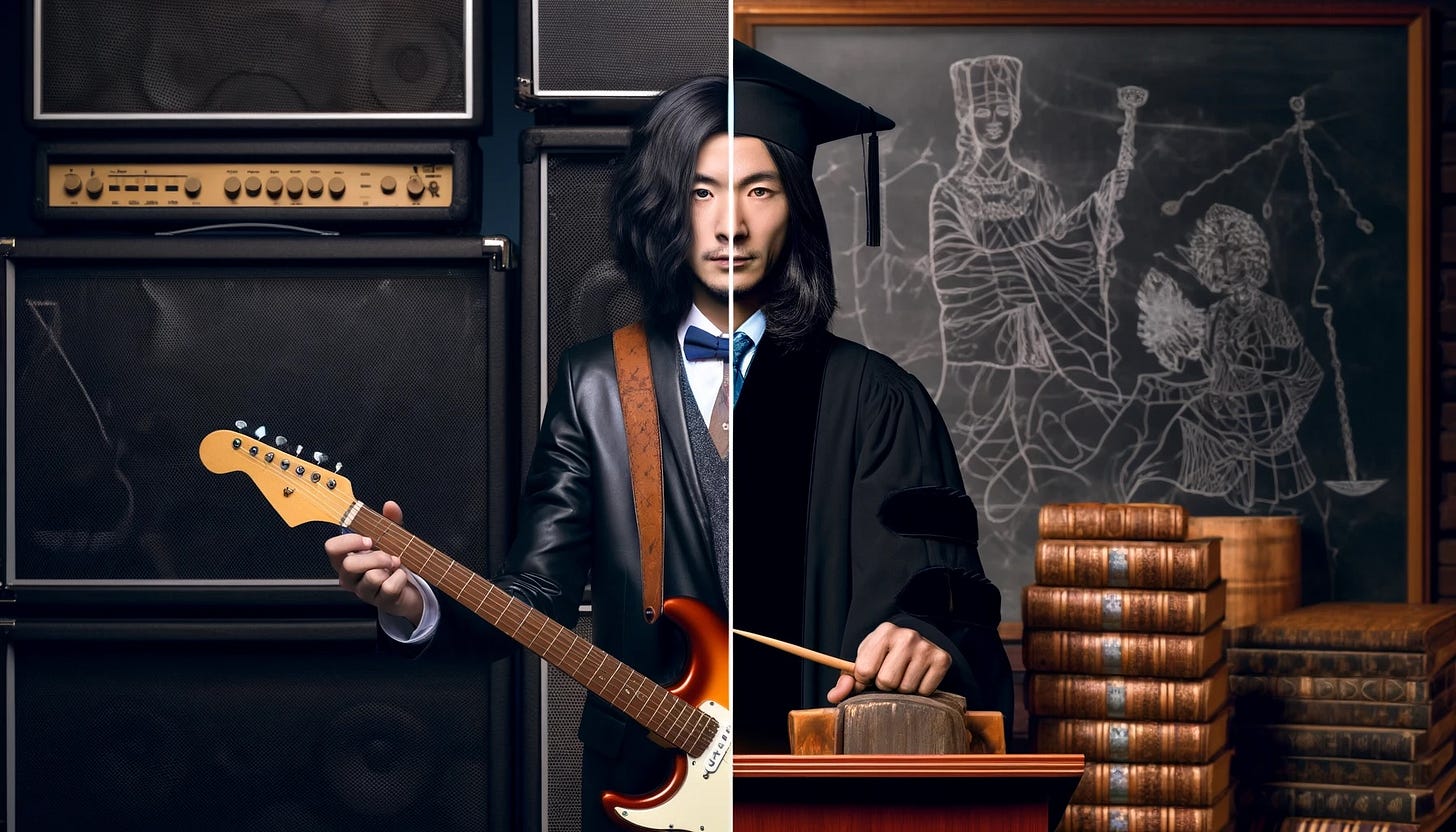

Books, Drugs, and Rock ‘n Roll

One of the most consequential decisions I’ve made to date was whether to drop out of grad school in 1996 to return to Tang Dynasty. I use “most consequential,” but not “hardest” because in the end there was nothing that hard about it. Sure, I had apprehensions and misgivings, but the decision itself was a no-brainer.

Except for one important area of overlap, the two callings — one merely avocational, the other vocational — couldn’t have been more disparate. They call for completely different skill sets, put one in nonoverlapping circles of individuals, and come with radically divergent lifestyles. I'm sure you can imagine the different dyads that it produced: high-volume, outwardly-directed excitement versus quiet interiority and contemplation, for example. Straddling the two, as I tried to in the early 90s when I’d head back to China for the summers, became less and less tenable. Some people, including Dr. Hedtke, the modern Chinese historian, suggested that I actually treat the rock scene as an academic topic. But that just laid bare something that I'd always suspected: Deep within me, I simply didn't believe that it was a worthy object of serious scholarly study — at least not for me. Perhaps I had a bit too much intellectual self-regard, and shouldn't have felt this way: after all, haven't several academics done good scholarly work on the Chinese rock scene? But I wasn’t an ethnomusicologist and didn’t aspire to be one.

This all came to a head in 1992, in the second summer I'd returned to China after 1989. I had rejoined Tang Dynasty, which had just released its enormously popular first album, and we toured along with Black Panther and singer Dou Wei’s new band Dreaming (做梦),in the southern Chinese cities of Guangzhou, Zhuhai, and Jiangmen. In July, while in Shenzhen between shows, we got word of some drug-related arrests in Beijing, and so many of the musicians decided that they wouldn't head back to Beijing right away, but hang around down south until it all blew over. Most of them smoked a little hash, which could be bought easily back then and which hadn’t previously been the focus of any law enforcement efforts we were aware of. Hemp grew wild all over China, and many musicians smoked openly, assuming — in most cases correctly — that the cops didn’t even recognize the smell of it.

Things were changing, though. Law enforcement was now cracking down even as harder drugs — heroin, chiefly — had started making inroads into the rock scene. A singer that the Arkansan Sean Andrews and I had recorded an album with in 1988 had, I heard by 1992 become an addict. Ding Wu informed me of this one night after we’d seen the drummer of another band open a tiny paper packet of off-white powder in a hotel room. That singer, he said, had told him of the excruciating pain he felt in the marrow of his very bones during withdrawal. He had wasted away and, Ding Wu told me, had grown almost unrecognizably gaunt, his skin sallow and his voice barely a croak.

My mother, who was in Beijing then, told me when I checked in one evening that she’d received a call from “a friend” in the Public Security Bureau, warning her that certain people her son was spending time with were moving into hard drugs. If I were smart, I would be a good boy and go back to graduate school. We heard soon aftward that a good friend of ours, who fronted another band, had been picked up just for hashish and had been jailed. Prior to this, none of the people who’d been nabbed were well-known.

I had a tearful heart-to-heart with Ding Wu a few nights later. He told me that as much as it pained him, he thought it would be better if I just went back to my studies, got my Ph.D., and came back when I had time to play the odd show with the band. "We'll always leave the door open for you," he had said.

The truth is that it was no harder a decision for me to leave the band then than coming back four years later would be. I was still enthusiastic about academia then, with ample support, a topic that fascinated me, and most importantly, professors who were generous with their time and interested in my development and my work. But equally important was my own assessment of my abilities as a musician. The fact was I was never very good — certainly not good enough to go on playing with a band as good as Tang Dynasty. I knew then that my limitations would only hold the band back.

When I arrived in China in 1988 with a guitar, a little Roland Cube Chorus 60, and a half-dozen pedals, I rated pretty highly among Chinese guitarists. But even then, had I spent an hour in a Guitar Center in any American city on a Saturday afternoon, I would have met 20 guitarists who were far more skilled and versatile. I was an amateur, competent at best. I was completely self-taught, unable to read music or understand theory, with serious physical limitations that my laziness about practicing didn’t exactly help me overcome. By 1992, amazing guitarists abounded in China. The lead guitarist who had replaced me in Tang Dynasty after our hasty departure in June 1989, Liú Yìjūn (刘义军), better known as 老五 (Lǎo Wǔ), was an astonishing shredder whose virtuosity was already becoming legendary. I couldn’t hold a candle to him. I knew it, and everyone knew it.

And so I went back to the States and announced my decision to Drs. Whiting and Hedtke that I intended to stay at Arizona to pursue a Ph.D. I had thought about going elsewhere; before leaving for China in 1992, I had asked for letters of recommendation for some other programs from Whiting, but he convinced me that were I to stay in Arizona, I'd finish quickly — before age 30 — and told me that going elsewhere would likely set me back by years.

The next three years in graduate school were productive for me but not because of my coursework so much as the teaching I took on: I was a teaching assistant pretty much every semester either for a survey history course ("Chinese Civilization") or for a survey humanities course ("Chinese Humanities.") I also taught at Pima Community College, and in the summers of 1993 and 1994 had my own summer school history courses I taught, in which I wrote the syllabus, assigned the readings, and wrote all the lectures. This was invaluable. Finally, in the spring of 1995, I taught a course at Arizona State University for Dr. Hoyt Tillman, a specialist in Song Neoconfucianism who was on sabbatical. The course was called "Chinese Thought and Way," and it tested my grasp of Chinese intellectual history. If you can't teach it, as they say, you don't really know it. In the fall of 1995, I passed my qualifying exams and began thinking about my dissertation topic, which was going to be on the emergence of technocracy in post-Mao China.

In these years I barely touched my guitar. But then, in May of 1995, the bassist Zhang Ju was killed in a motorcycle accident. He and Ding Wu had both gone down the path I had feared when I first saw that drummer with his little paper packet. I don't doubt that Zhang Ju's accident had to do with his habit. I was devastated. Over the next few months, my sister Mimi, who had been living in Beijing, started dating Ding Wu, who told her he had gone clean. This turns out not to have been the case. They had a new bassist, Gù Zhōng, whose physical resemblance to Zhang Ju was uncanny. But while he could play Zhang Ju’s bass parts, he couldn’t serve his other, crucial function in the band: peacekeeper. Zhang Ju had been the only one able to keep Ding Wu and Lao Wu from one another’s throats, and with him gone, the band fell apart quickly. In early 1996, Ding Wu and Mimi began working on me to come back to the band.

By this time my skills on guitar — never particularly impressive, as I’ve said — had atrophied further still. Despite this, they persuaded me to return to Beijing, and I did, in July of 1996. Soon after landing, we were in the studio to record a song I’d written for Zhang Ju called “Your Vision,” which appeared on a compilation in his honor. I tried in earnest to broker a rapprochement between Ding Wu and Lao Wu, telling them — despite my own selfish and vain longing to be part of a famous rock group — that the four of them, without me, were the band the fans had come to love. There was no way in hell I’d ever be able to play Lao Wu’s shredding solos, in any case. I urged them to patch things up, offering to play a role as an informal producer and to help out with things I’m actually decent at, like arranging.

I’ve often, and less than honestly, presented my decision to drop out of grad school as more pull than push: who wouldn’t choose the allure of life as a musician in a top band over the grind of academia? The truth is I was full of misgivings about rejoining Tang Dynasty. I’ve never in my life suffered greater imposter syndrome. I knew I was disappointing my parents and my professors — and what worse for a kid who’d grown up with all that Confucian socialization? — and knew that I was risking legal peril because of continued drug issues with the band. What’s more, I was looking for an excuse to quit academia.

In the spring of 1996, in fact, my father asked me to start looking into the business of aluminum recycling, in which he saw big opportunities in China. Some acquaintances in Beihai, a coastal city in Guangxi, were looking to build an aluminum recycling plant using state-of-the-art American gear, and I began looking seriously into this, pricing different systems and evaluating the technology behind them — shredders, air knives, magnetic separators, conveyors, furnace systems — and figuring out what I could of China’s recycling ecosystem. They offered me a job as general manager of a facility there on the strength of my proposal: It would have come with a house on the beach and a driver. It’s laughable in hindsight, and I’m sure I would have made an absolute hash of it, as I’m just a terrible manager to begin with. But even then I realized this was just too far off from any life I’d imagined for myself, and I knew I was kidding myself to think I could run a business like that. I made up some excuse and declined.

I was also alarmed, then, by the incursions of various forms of critical theory into academia. The theories themselves — postmodernism, poststructuralism, and what have you — did contain some valuable ideas, and I recognized that even then. But they tended to bring with them this horrible obscurantist prose, and (I felt very strongly) in their embrace of epistemological skepticism undermined scholarship itself. I took part in a Foucault reading group chaired by a professor of Japanese religion in our department and was shocked by the way some of the younger faculty members seemed, ironically, to embrace these critical theories completely uncritically.

But at a more fundamental level, I also began to wonder whether I had the disposition for serious scholarship. Would I really be able to spend whole days in the stacks, reading dusty tomes and writing index cards? Did I possess the discipline to produce and to keep on producing if I wanted my academic career to actually go anywhere? And that's even if I ever were to land a tenure-track job: People in the area studies, as opposed to a discipline, were having a great deal of difficulty finding good work back then, as they still do now.

All of these things — my own self-doubt, my growing discomfort with the direction that the academy was going, and the lack of good employment prospects — helped me make up my mind to leave, even more than the allure of unearned rock stardom.

I have very mixed feelings about the album that we finally released in early 1999, 《演义》(or Epic) — the hard-won fruit of years of recovery, managing difficult personalities, long rehearsals, and complicated business negotiations. That it got done at all was a minor miracle. But listening to it again today I swing between moments of immense pride and profound embarrassment, especially over the way we recorded the guitars, and in our decision not to have it professionally mastered. As we recorded, the producer, Otomo Koetsu, had done such a meticulous job and shown such patience. Still, some of the composition holds up well, and every once in a while I’m paid an enormous compliment when guitarists I really admire cover material from that album and talk about its influence on their playing, and on the direction of Chinese rock and Metal. My stamp is on it, for better or worse.

I’ve related the story of my departure from the band in June of 1999 in other places, so I won’t go into any detail here except to say that I now recognize how much of it was my own fault. I failed to practice cognitive empathy in the aftermath of the U.S. bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade in May 1999 and just mouthed off with what I believed to be true without sufficient regard for how that event felt to my Chinese bandmates. I never really reckoned with my own privilege, either, when it came to commercial considerations in our music, and I blithely hewed to idealistic notions about “pure art” and refused to compromise with market realities. I always knew I had other career paths to fall back on — indeed, career paths to which I was better suited than the one I was then on. I took it seriously when I was doing it, in part to try to banish my deeply felt imposter syndrome, but part of me always knew that rock music would ultimately be relegated to a hobby for me.

Foreign Friends

1999 had been a doozy of a year for me. Tang Dynasty’s album came out in January, and immediately we were playing constantly, traveling all over the country to warm receptions in packed houses. We played stadiums I’d never have dreamt of playing: 30,000 people in some venues. I bought a car, a red Jeep Cherokee, with my then-girlfriend Jessica, a pop singer. I had begun to make some friends in expatriate circles in Beijing, and we hung out in the storied bars of Sanlitun’s South Street — especially the Hidden Tree and the Jam House, where both my circles, Beijing rock musicians and a peculiar type of Chinese-speaking expat drawn to Beijing’s arts and culture scene, tended to overlap. China continued to offer up more than its share of drama, of political and intellectual puzzles — the Falun Gong sit-in of April 25, for instance. Jessica’s mother had been FLG-curious, and I remember her showing me some pamphlets just weeks before — my first awareness of this particular brand of spiritual belief. Suddenly thousands of adherents were staging a peaceful sit-in around the Zhongnanhai leadership compound. And then, just two weeks later, on Saturday morning Mat 8, my brother Jay called me to tell me that the Chinese embassy compound in Belgrade had been bombed by the United States. That set in motion events that would lead me to depart Tang Dynasty, as I’ve talked about previously. I got my teeth loosened by an angry former friend over the embassy bombing: He hit me in the jaw with a full beer mug in a drunken pique of nationalism, heightened no doubt by the fact that he used to date Jessica.

Life changed abruptly. The night before the Falun Gong sit-in, at an Overload (超载) show at a live house called Keep in Touch, I had been introduced to a Shanghai-based journalist who, like me, was Chinese American and had parents who had emigrated via Taiwan to the States. By mid-May, I had broken up with Jessica and had begun a new romance with her, one that brought me into closer acquaintances with many journalists both in Beijing and in Shanghai, a city I’d begun visiting frequently. My life, which had been lived very much in Chinese as I kept company mainly with my non-English-speaking bandmates and girlfriend, now switched suddenly into mostly English. More and more of my friends were foreigners, especially after I took a job with a Shanghai-based internet startup called ChinaNow.com, as the Beijing office manager and English editor-in-chief.

It’s not lost on me that my ethnicity was another source of privilege. On balance, foreigners who’ve spent time in China — at least in the major metropolises — come away with the sense that the Chinese people are warm, hospitable, and welcoming to foreigners. But others report an entirely different experience, and I’ve been privy to enough candid conversation over the years to know that xenophobia and bigotry can still be serious issues. I know that my phenotype and my decent Chinese have been enough to make me in-group more often than out-group and that this far outweighs the relatively few instances in which perceived foreignness is an actual advantage, or Chineseness works against me. I’m more likely to hear the undiluted, unvarnished opinions — not the ones for official consumption, and not the polite version for “foreign friends.” I can blend in if I want to. I can occupy two worlds, and serve as an intermediary between them. It’s an enormous leg up that I try not to take for granted.

This was, I think especially advantageous in the years after ChinaNow’s demise, when I was working as a reporter. I felt like I was able to gain confidence more readily, and that I could solicit frank perspectives from interview subjects, and not just off the record: “自己人 zìjǐ rén” — “one of us,” someone would say to me almost conspiratorially, then go on to say something they were confident would resonate with me as “one of us,” as a Chinese. I wonder whether — had I been a Black, or brown, or white American reporter, speaking to him only in English — I could have pried the pugilistically nationalistic quotes from Jack Ma that I managed to for an interview for Red Herring, where I worked from 2004 to 2007. On a sultry July morning in 2005, on a balcony in Hangzhou’s Shangri-La Hotel overlooking the tomb of the patriotic Song dynasty general Yuè Fēi 岳飞, I used the location and some basic knowledge of Chinese history to prompt him into a long nationalistic harangue. Rival eBay’s CEO Meg Whitman, Ma claimed, was spending the summer in China trying to save eBay’s business against his own proudly insurgent upstart, Taobao. Did not Yue Fei also fight off an invasion by foreigners? I innocently suggested. That was enough to get him going. “Didn’t anyone ever tell Meg Whitman never fight a land war in Asia?” he began. He went on with gems like “They’re trying to land their B-52s in our rice paddies!” and compared Whitman coming to China to fight him to “George Bush strapping on an M-16 and searching the caves in Torabora personally looking for Bin Laden.” It made for great copy.

The Origins of Optimism

Seeing China from certain hilltops and not others afforded me a sunnier, more optimistic view than would have been the case had my focus been, say, human rights. If you were a journalist in the mid-aughts in Beijing covering tech entrepreneurs and not, say, democracy advocates or Tibetan self-immolations or unsuspecting farmers dying of AIDS from coerced blood-selling, you’re going to see a better side of China. It’s not hard for me to imagine what my attitude could otherwise have been, just as it’s easy for me to imagine that had I experienced the violence in 1989 personally, my views might be different from what they are. I try to make room in my worldview for those alternative, imagined emotions, too. But I recognize there’s a big difference between the products of such efforts at empathy and direct, firsthand experience. I only hope that others will do me the same courtesy: to make an effort to see what China might be like viewed from another hilltop, where the landscape before them isn’t so bleak, but can indeed be charming, attractive, and even inspiring.

My personal life was also a source of nourishing sunshine. In 2001, I joined forces with a singer-guitarist named Yang Meng, and we started a band called Chunqiu (春秋) that offered all of the fun and none of the drama of my former band. We continued playing together until just before I left, in 2016, never achieving anything close to fame but writing a lot of music I was very proud of. More importantly, In October 2003, I married Zhang Fan. A quintessential Gen X Beijinger literally raised in the hutongs of Dongcheng, she married me despite my lowly status as a washed-up rock musician whose only income was from freelance reporting gigs and doing occasional subtitles for indie films. Her faith in my potential paid off, and as my circumstances improved we were able to live comfortably — indeed, blissfully — and raise two wonderful children in Beijing. Fanfan had never lived abroad, spoke no English, and wasn’t particularly interested in the things that fascinated me — history, philosophy, or politics. But that was a feature, not a bug. My daily interactions with her and her remarkable family helped me to a much more intimate understanding of the minds of Chinese people, and to an instinctive grasp of how they are likely to respond when faced with a range of circumstances.

For much of my life, well into my twenties, my parents were both members of the U.S.-China People’s Friendship Association, a group of well-meaning people who were wholly sincere, as far as I could tell, in their desire to promote people-to-people diplomacy between China and the U.S. The members we socialized with both in Upstate New York and in Tucson were mostly older, white Americans and some Chinese Americans of my parents’ generation. The organization drew fire for its unmistakable pro-mainland tilt, but its activities were mostly innocuous: arranging trips to China and hosting receptions for visiting scholars and dignitaries.

In hindsight, I could certainly find fault with their ready credulity, their lack of sophistication especially on the issue of Taiwan, and the lack of sympathy among many members for the protesters after the tragedy of 1989. Their idea of “friendship” went beyond how I’d define mine now: Where I would frame friendship as a mutual readiness to extend the benefit of the doubt, a baseline of goodwill, an emphasis on common ground and shared goals, and an approach to resolving differences in a spirit of constructive criticism and not just finger-pointing and point-scoring, their approach to friendship seemed far too pollyannish and unwilling to risk even the most deserved criticism.

But I have to credit the USCPFA for nurturing a seed that my parents had already planted in me, and would go on to become a core part of my identity — and a core “prior” of which I’ve never made a secret: my aspiration to be a bridge-builder.

I suppose it had flowered by the time I started graduate school. It was given impetus by my sense that so many people had watched events in Tiananmen unfold without really getting the full picture, without understanding the arcane semiotics. I only came to recognize this sense of mission when, for the first time, I started a job that took me very much off mission. On a consulting gig in Shanghai for a major American automaker in 2007, I met a senior advertising executive who apparently liked the cut of my jibe and recruited me for a position for which not only I was unqualified but that, I quickly found, I just didn’t like. Teaching Chinese history, playing in a Chinese rock band as an American, working as a reporter on the Chinese tech beat — disparate as those occupations were, they all were to greater and lesser degrees “on mission.” This new job, which I only held for less than two years, was decidedly not. No fault of theirs: I was a terrible fit both in terms of skills and in terms of the company culture. I was entirely out of my element and found no purchase within the organization.

Only on returning to work that was very much “on mission” for the remainder of my years in China did I come to realize how important the mission was to me. While still at the ad agency, I’d rekindled a friendship with Victor Koo, founder of Youku, the internet video site later acquired by Alibaba. He had been an advisor to ChinaNow.com, and had served as second in command at Sohu.com for many years. A fellow Cal graduate, he was always one of my favorite Chinese internet entrepreneurs. When he asked me to come to work for him to run media relations, I floated the idea of taking my hours down to half-time with the ad agency. They were only too happy to do so. Two years later, I took a full-time job with Baidu, the search engine.

I joined Baidu just a few months after Google had announced its pullout from China. I couldn’t have joined at a better time, and I realize now that the two years following Google’s pullout were for Baidu a bit like America’s 9/11 distraction had been for China. Those were the fat years: For quarter after quarter, the company beat EPS estimates, bulked up on staff, and began exploring other markets. Work was a delight. The company’s culture was very American: egalitarian, flat, and anti-hierarchical. To my delight, as I got to know the company’s leadership I found them all to be cosmopolitan, liberal, and very forward-thinking. They chafed over internet censorship and pushed back wherever and whenever they could. They really did believe in expanding the information horizons for ordinary Chinese netizens. My own techno-optimism, already abundant from my years writing on brilliant Chinese tech entrepreneurs, was bolstered by those years at Baidu — and further still when the company hired legendary AI guru Andrew Ng, with whom I had the pleasure of working very closely.

Absolutely Relativist, or Relatively Absolutist

The years at Baidu, and especially those early years when so much of my role there interacting with media involved talking about internet censorship, crystallized for me a basic tension in my thinking — a tension I’d long been aware of but never really bothered to try and articulate, and a tension not just in my own thinking, but one with great relevance for the broader discourse on China. It’s one I believe deserves a lot more attention and discussion. In thinking about censorship, I realized that my own instinctive distaste for it in an American context contrasted with my grudging acceptance of the idea that some level of censorship might be necessary in a Chinese context. (I’ve written about this elsewhere if you’re interested). This extended to many other issues I routinely encountered in China, whether big (say, human rights) or small (say, personal habits).

I embrace the normative claim that, at least in the abstract, there are universal values to which humanity should aspire: eliminating cruelty, allowing political participation, allowing free expression, the rule of law, and so forth. But I also accept that the fact that some societies have been able to move toward those goals while others have struggled to do so is not because of some moral superiority on the part of those that have or moral failing on the part of those that haven’t. A great deal of it is the luck of the draw, the result of highly contingent historical processes. I don’t believe that there’s one correct answer, valid across all cultures, for the Trolley Problem. But there’s something unsatisfying if the only common denominator is that yes, human life has some intrinsic value. The challenge for me — and this informs to a great extent how I think and talk about China, or indeed any society — is to reconcile absolutist beliefs, which are too often taken to extremes by proponents of universal values, with relativist beliefs, which are too often deployed by apologists to excuse atrocious behavior.

Listeners to the show will recognize another related set of basic tensions that define my perspective on China and rank among my priors. One that I’ve hinted at previously is the constant tension in China studies — indeed, in the study of any society — between the quest for generalizability and the recognition of the uniqueness of that individual society. What is human, and what is specifically Chinese? And isn’t “human” too often conflated with “western”? I’ve lost count of the number of guests on Sinica to whom I’ve put this question in one form or another; few, understandably, have a useful rule of thumb they apply. It’s an art — perhaps the art. The political scientist Iza Ding, who is my guest on the show this week, said something I thought was profound in its simplicity and expressed better than I could have what my approach, I hope, has always been:

“I think the goal is to say things are sui generis when they are sui generis, and say things are universal when they are universal. But if somebody says something is sui generis, let’s not punish them for that. I think generalizability is a very good goal, but it shouldn’t be our only goal. It shouldn’t be the Holy Grail especially when we still know so little about this fast diverse world and its myriad cultures, languages, and histories. Let’s stop asking questions like, “Why China?” to somebody who studies China, or “Why Turkey?” to somebody who studies Turkey. These questions imply that knowledge about Turkey or China is not as valuable or universal as knowledge about America or Americans. A good liberal should not make those assumptions.”

I’ve now run up against my self-imposed word limit for this installment, and there are still many topics I’d like to cover, so… to be continued. Next week, I’ll talk about why Taiwan has figured so little into the story so far despite my parents having spent important, formative years there; about my reckoning with neoliberalism during my time in China; about what I’m trying to do with the Sinica Podcast; about some of the puzzles that still bedevil me when it comes to getting my head around China; and about my own emotional state as I’ve watched the relationship between the two countries I know and love best come to such a wretched, depressing state.

Hey Kaiser - I spent a few minutes looking around for the writing you allude to about some level of censorship being necessary in China, but didn't find anything that seemed quite right. Can you link to one of the pieces you have in mind? Would love to read more.