Schopenhauer’s East Asian Renaissance: How a forgotten 19th-Century German philosopher became a TikTok sensation

A guest post by Iza Ding

Iza Ding is Associate Professor of Political Science at Northwestern University, and the author of The Performative State: Public Scrutiny and Environmental Governance in China. Check out and subscribe to her Substack “I Just Kant” here. And listen to her fantastic interview from last year on the Sinica Podcast here.

Two centuries after being largely ignored in the West, Arthur Schopenhauer has become a cultural sensation in East Asia. His aphorisms on how to live a good life are flying off bookshelves in South Korea and China, where the high-achieving yet existentially adrift find solace in his brand of philosophical pessimism. Little do they know that two centuries ago, it was Asia that inspired him.

I spoke of Schopenhauer as modern. I might have called him a futurist. — Thomas Mann

I. Hegelplatz

This spring, I lived on Hegelplatz, a quiet nook tucked behind Museum Island in the heart of Berlin, just around the corner from the Pergamon Museum, which has been closed for renovation since 2023. The work, they say, may drag on for twenty years—almost as long as it took to build the Great Pyramid of Giza, around 2600 BC.

My daily routine included strolls down Friedrichstrasse for zhajiangmian at Liu Nudelhaus, or up Unter den Linden to take in the hodgepodge of demonstrations at the Brandenburg Gate: pro-vegan, pro-Ukraine, pro-Kurdish Women’s Movement, pro-restoration of the Kaiserreich. On my way home, I’d stop by Dussmann das KulturKaufhaus to pick up a book, a pair of socks, or ink for my fountain pen. Dussmann is only steps from my building on Hegelplatz, where a bronze statue of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) stands sentry at the entrance.

When my friend Deb visited me in Berlin, she laughed and said, “Of course you’d live on Hegelplatz.” I realized she had come to think of me as a philosophical person, which made me worried for my sanity.

Deb’s parents were Jewish immigrants to the U.S. Her father left Berlin in 1939 and arrived in New York in 1940 via Holland. In high school in the 1970s, she came across a New York Times article lamenting that too few Americans were learning languages, and that only two hundred people in the country were studying Chinese. She put down the paper, turned to her mother, and said she would study Chinese in college. She applied to Harvard and got in.

In her freshman year, Deb read Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, on the recommendation of a high school history teacher she liked. But she found them of little practical use. So she doubled down on Chinese, taking courses in language, history, literature, and society in the East Asian Studies program.

After college, she joined the State Department. Her first assignment took her to India, where she learned Hindi—a language that, to this day, occasionally slips into her Spanish. Then came two years in New Zealand. On her third tour, she finally went to China, serving as an economics officer at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. Two more China tours followed: first at the Guangzhou Consulate, again as an economics officer; then back to Beijing, this time as a science and technology counselor.

After twenty-one years in foreign service, Deb dyed her hair purple and decided to go to grad school—because how else does one have a midlife crisis? But before her time in government ended, she did something that would inadvertently change many people’s lives, including mine.

Deb thought Beijing's air pollution was out of control and asked the embassy to install a monitor. The embassy obliged, placing one on its roof. It began posting hourly readings on Twitter, which, at the time, was still accessible in China. The resulting brouhaha was more than she anticipated. Suddenly aware of how severe urban air pollution had become, the Chinese middle class flipped out at their government. Thus began the state’s decade-long “war on pollution.”

But that’s only the official story—the version told in media and academia. To learn how it really happened, subscribe to my Substack to receive a future essay looking back at the “airpocalypse,” fifteen years later.

In 2012, Deb began her Ph.D. in political science at UC San Diego. I was already at Harvard, working on my doctorate in the same field. Both of us wrote our dissertations on China’s environmental governance. We met in 2015. I liked her immediately. What I didn’t know was that I sort of had Deb to thank for my dissertation topic.

You don’t know what you don’t know.

II. “Hegelry”

But I’m here to tell you about Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), a philosopher Deb did not read in her freshman quest to become an “educated person.” And that’s a good thing—if she had read Schopenhauer, she might never have bugged the U.S. embassy to install that air pollution monitor. And I might not have a dissertation, a job, and a Cornell University Press book pretentiously titled The Performative State. (At least I didn’t call it The State as Will and Representation as I almost did.)

Deb wouldn’t have read Schopenhauer because he simply isn’t a thing in the U.S. For years, I’ve been casually polling American intellectuals: Have you read Schopenhauer? So far, I haven’t met anyone who has.

That’s not to say Schopenhauer is a thing in his home country, Germany, either. For most of his life, he lived in the shadow of Hegel—a shadow that followed him into death.

Did he even want to be a thing?

He was one of those people who loathed the establishment and screamed from the margins. He had the luxury to do that—to “live for philosophy, not by philosophy”—thanks to his inherited wealth. He made no effort to hide his disgust with professional academia, which he saw as careerist and intellectually bankrupt. Instead of truth, it served institutional power, religious orthodoxy, and state ideology. While everyone in Berlin threw themselves at the feet of Hegel, Schopenhauer called him a “spiritless and tasteless charlatan,” a “crude and nauseating charlatan,” an “ignorant charlatan,” a “shameless charlatan who wants to fool simpletons.” The simpletons, he thought, were everywhere:

“A majority of those in my discipline … were employed and paid to disseminate, to praise… the worst of all philosophies, named Hegelry.” (Schopenhauer 2014, 123)

Hegelry (Hegelei) was one of his neologisms for stupidity, along with Hegel-farce, Hegeljargon, and sometimes just Hegel.

In a way, Schopenhauer set himself up for obscurity.

But he also craved public attention—“more than he would like to admit to himself,” writes his biographer Rüdiger Safranski. “Too proud to seek a public, let alone to curry favor with it, he would nevertheless secretly hope that the public would seek him” (Safranski 1991, 151).

When he moved to Berlin in 1819, he brazenly scheduled his lectures at the same time as Hegel’s, thinking he would lure the audience away from the reigning philosopher-king. The gambit failed spectacularly: Hegel’s lectures played to packed theaters, while Schopenhauer’s were so poorly attended they were canceled the following year.

No wonder Deb never read the guy.

III. The Wicked Will

But even if Deb had read Schopenhauer, she would still have gone to India and China. She would have made the trips that Schopenhauer could only dream of. For Asian philosophy—Buddhism in particular—played a formative role in his thinking.

He later wrote: “At the age of seventeen, without any advanced schooling, I was as overwhelmed by the wretchedness of life (Jammer des Lebens underlined in his notebook) as the Buddha in his youth when he saw illness, old age, pain, and death” (App 2010, 39).

Therein lies the first principle of Schopenhauer’s philosophy: life is suffering.

This pessimism—the belief that the universe does not exist to please man—sets him apart from nearly every other Western philosopher, most of whom were optimists in one way or another.

But it would be naive to equate his pessimism with nihilism. The Schopenhauer Express departs from the station of despair, but it’s bound for nirvana.

How?

Schopenhauer believed there were two types of “world-religion.” The first, optimistic and theistic, imagines a good world created by one benevolent God, with evil and suffering projected outward into a cosmic dualism: good versus evil, heaven versus hell.

The second, pessimistic and atheistic, sees suffering, evil, and sin not as intrusions but as intrinsic to the fabric of existence. There is no God versus Satan, no here versus there—only this world, and its inescapable dukkha.

The second view of the world accords with Schopenhauer’s lived experience. He was, without a doubt, a pessimistic person. Where that pessimism came from is unclear. According to Safranski’s biography, it may have grown out of a cold and exacting father, and a strained— eventually broken—relationship with his mother.

But Heinrich Floris and Johanna Schopenhauer, though not without their issues, were by no means horrible parents by early-19th-century standards. His childhood wasn’t all that bad; it seemed rather good. His mother was a popular literary figure in the Weimar of Goethe (1749-1832). His father left him a fortune, which allowed him to become a free-ranging philosopher. Sure, he had his share of conflicts with both parents, but reading their letters, one doesn’t get the impression that they were so unloving as to explain the making of a gloomy philosopher-child.

It’s more likely that young Schopenhauer suffered from depression or some other form of neural divergence—something probably correlated with his high intelligence and sensitivity. Goethe left a telling note in his diary after spending time with Schopenhauer: “a usually misjudged but difficult-to-know deserving young man” (Safranski 1991, 251). Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), the chronicler of Western philosophy, was not a fan, calling him “completely selfish,” “extremely quarrelsome,” and “unusually avaricious,” adding, “It is hard to find in his life evidence of any virtue except kindness to animals” (Russell 1945, 758). Thomas Mann (1875-1955), by contrast, was a huge admirer, but still discerned his darkness, describing him as “misanthropic,” prone to “over-strained irritability,” and “bi-polar” (Mann 1939, 26, 27, 30).

My bet is that he would have become a philosopher either way, rich or poor, loving parents or no loving parents.

Regardless of the source of his pessimism, the universe presented itself to Schopenhauer as lawless, irrational, and aimless—diametrically opposed to Hegel’s belief that history is marching toward a harmonious, glorious end. For Hegel, history is a slow but purposeful unfolding: dialectical, stepwise, zigzagging towards freedom and justice. This idea—that history has a purpose—famously influenced Marx, who then turned Hegel on his head.

Schopenhauer saw no such arc, Hegelian or Marxist. He rejected the idea that history has a telos or that the world contains any inherent moral order. Instead, he saw a blind, striving force at the heart of existence—what he called the Will (der Wille)—pushing life forward without purpose, reason, or rest.

This wicked Will broke decisively with the divine will in Christian theology. Schopenhauer’s philosophy severed itself from Christianity altogether, rejecting its providential optimism and moral teleology. He was lucky to be ignored—had more people been paying attention, he might have found himself in serious trouble with the authorities.

He saw the wicked Will as the universal source of our primal urges, instincts, and cravings. It doesn’t know or think—it just strives. Our intellect spends most of its energy rationalizing those urges. Our reason is the light that illuminates the path the Will already wants to take. Our morals are summoned forth by the Will in service of its struggle for survival, reproduction, and dominance.

This thesis finds solid backing in contemporary psychology. Today, we give the mind’s work on behalf of the Will scientific names like “confirmation bias,” “motivated reasoning,” and “moral instincts.” (See, for instance, The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt.) Mann called Schopenhauer the father of modern psychology, and he was right.

The endless striving of the Will leads to Schopenhauer’s conclusion that suffering is the baseline condition of existence. Life, he famously wrote, is “a violent oscillation between pain and boredom” (Schopenhauer 2006, 11). We suffer when our desires are frustrated, and we grow bored once they are fulfilled. Pleasure is but a brief reprieve—a narrow bridge between the two abysses.

Nonetheless, Schopenhauer believed we can—and must—rise above the agony of existence to find a kind of tranquility, even meaning, in a world that offers neither by design. We do so through the renunciation of the Will: that insatiable hunger for possessions, status, approval; through aesthetic transcendence—art and music—which lifts us, however briefly, beyond the tyrannical grip of the Will and joins us to something larger than ourselves, something eternal; and through the cultivation of a rich inner life, shaped not by external noise but by the quiet labor of knowing and self-knowing.

And above all, through compassion. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy captures what Schopenhauer means by compassion beautifully, so I’ll simply let it speak:

“By compassionately recognizing at a more universal level that the inner nature of another person is of the same metaphysical substance as oneself, one arrives at a moral outlook with a more concrete philosophical awareness… It is to feel directly the life of another person in an almost magical way; it is to enter into the life of humanity imaginatively, such as to coincide with all others as much as one possibly can. It is to imagine equally, and in full force, what it is like to be both a cruel tormentor and a tormented victim, and to locate both opposing experiences and characters within a single, universal consciousness that is the consciousness of humanity itself. With the development of moral consciousness, one’s awareness expands toward the mixed-up, tension-ridden, bittersweet, tragicomic, multi-aspected and distinctively sublime consciousness of humanity itself.”

This brilliant union of pessimism and humanism gave Mann an epiphany:

“The assertion that the one in no wise excludes the other, and that in order to be a humanist one does not need to be a rhetorical flatterer of humanity” (Mann 1939, 24, italics added).

This epiphany—that one could grieve the world and still care deeply for its inhabitants—is essential. In America especially, there often seems to be an unspoken pressure to project happiness and positivity even in the face of private or collective suffering. (Never say “Not good” when asked “How are you?”) As if sorrow were weakness, as if anger at injustice a kind of personal failure. As if, despite hunger and genocide, one must still look on the bright side, count one’s blessings, and be a “rhetorical flatterer of humanity.” Some “politics of joy,” so to speak.

Instead, Schopenhauer’s ethics allows one to “take philosophy without having to persuade themselves that all evil can be explained away” (Russell 1945, 751). Or, as Mann put it:

“His pessimism—that is his humanity.” (Mann 1939: 29)

You begin to understand why Einstein kept a portrait of Schopenhauer in his study, why young Nietzsche read him and decided to become a philosopher, and why Tolstoy called him “the most brilliant of men” (2015, 221).

IV. A Wonderful Agreement

Anyhow, teenage Schopenhauer was overwhelmed by the wretchedness of life, and adult Schopenhauer found what he called a “wonderful agreement” between his philosophy and Buddhism: their recognition of worldly suffering, their moral systems that do not exclude animals, and their striving for transcendence in this life. The resonance was so strong that he became worried he had unknowingly stolen his central idea in The World as Will and Representation from a Chinese text—despite no one accusing him of it. He then spent years proving to himself that he did not plagiarize Buddhism (App 2010, 55).

Later, Schopenhauer cited sinology as one of the “empirical sciences” that confirmed his philosophical ideas. Since what he considered “the most advanced civilization” and the “majority of its 361 1/2 million inhabitants” in 1813 were Buddhists, this constituted planetary proof of his thesis. He wrote that other Europeans had failed to notice due to their vanity and “their pushy eagerness to teach the ancient Chinese people their own comparatively recent beliefs” (App 2010, Appendix 8).

As to other Chinese “religions,” he dismissed Confucianism as “pedantic” and full of “nauseous platitudes”: “a trite moral philosophy … only for scholars and politicians,” and regarded Daoism as insignificant (App 2010, 135). The irony is that his ideas are often compared to Daoism.

If Schopenhauer had been a better comparativist, he might have seen Confucianism playing the same role in Chinese society as “Hegelry” did in German society: a state-sponsored orthodoxy propped up by mediocrity masquerading as wisdom.

V. Schopenhauer Fever

This backstory is known to few of Schopenhauer’s contemporary readers in East Asia. Two centuries later, they discovered him much as he once discovered them. They are not reading him because he collected Buddha statues and called himself a Buddhist, but because certain threads in his thought strike a hard nerve.

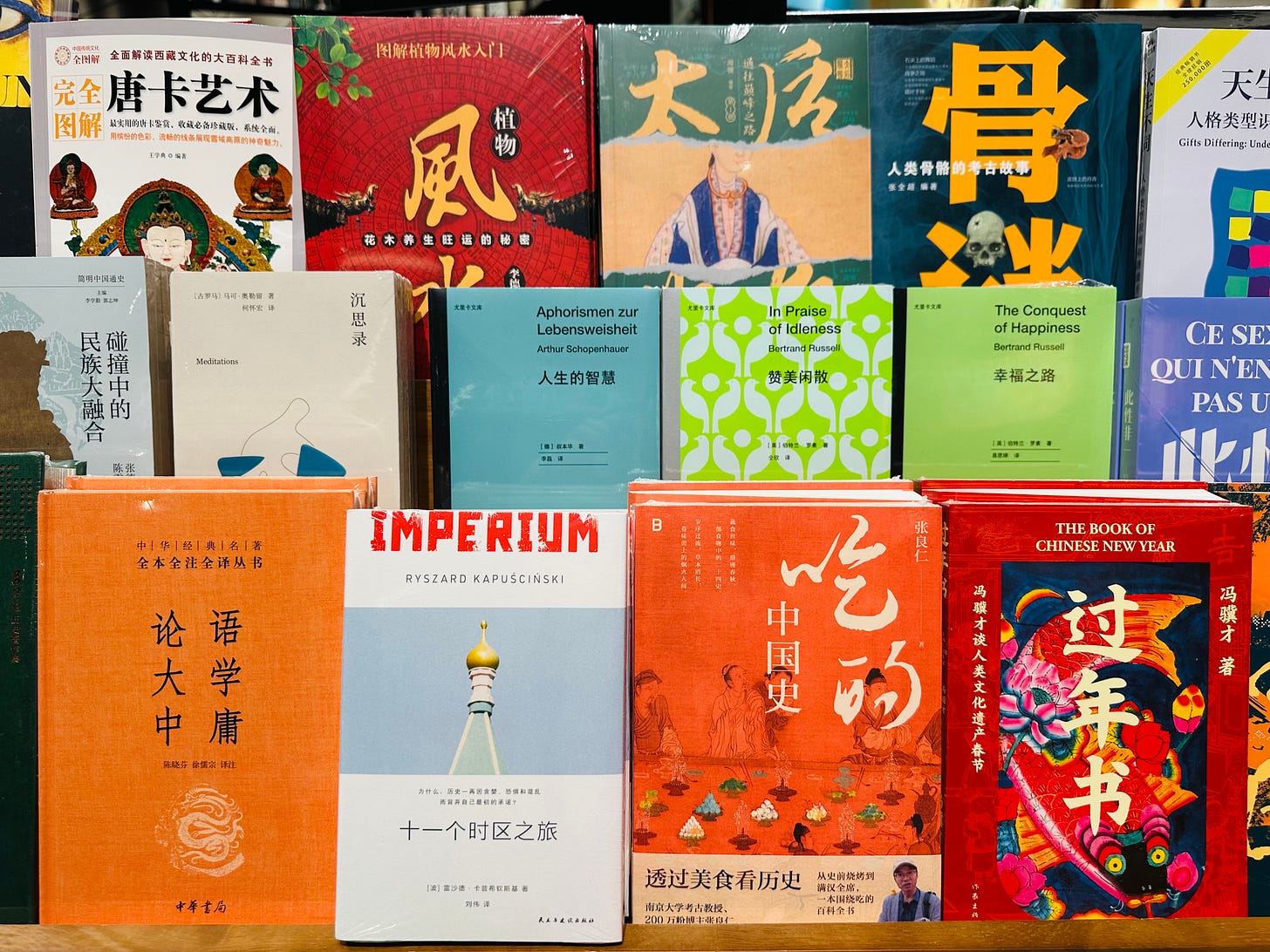

Walk into a bookstore in China or South Korea today, and you’ll likely find Aphorisms on Practical Wisdom (also translated as Aphorisms on The Wisdom of Life), or some other title by or about Schopenhauer, sitting on the front shelf.

Exhibit A is a photo I took at Sisyphus Bookstore in Hangzhou. Schopenhauer is nested between Russell’s In Praise of Idleness and The Conquest of Happiness on one side, and Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations on the other—some perennial favorites among Chinese readers

Exhibit A: A display shelf in Sisyphe Bookstore in Hangzhou, July 2025

As I mentioned earlier, Russell disliked Schopenhauer, despite their shared, if unacknowledged, connection to China. He never took Schopenhauer seriously, as evinced by several misreadings. But most of his disdain was directed at Schopenhauer’s character, criticizing him for not practicing what he preached, and noting that he “habitually dined well, at good restaurants” (Russell 1945, 750).

As for Marcus Aurelius, there is a clear overlap between Schopenhauer’s quietism and the Stoics—between Meditations and Aphorisms on Practical Wisdom. This is not surprising, as Schopenhauer admired the Greeks, and preferred the old gods to the new.

Exhibit B is from the East-West Bookstore at Zhejiang University. Safranski’s biography of Schopenhauer holds a central, cover-facing position. Schopenhauer would have been pleased to see that Hegel serves as little more than his bookstand here.

Exhibit B: Philosophy shelf of Zhejiang University’s East-West Bookstore, June 2025

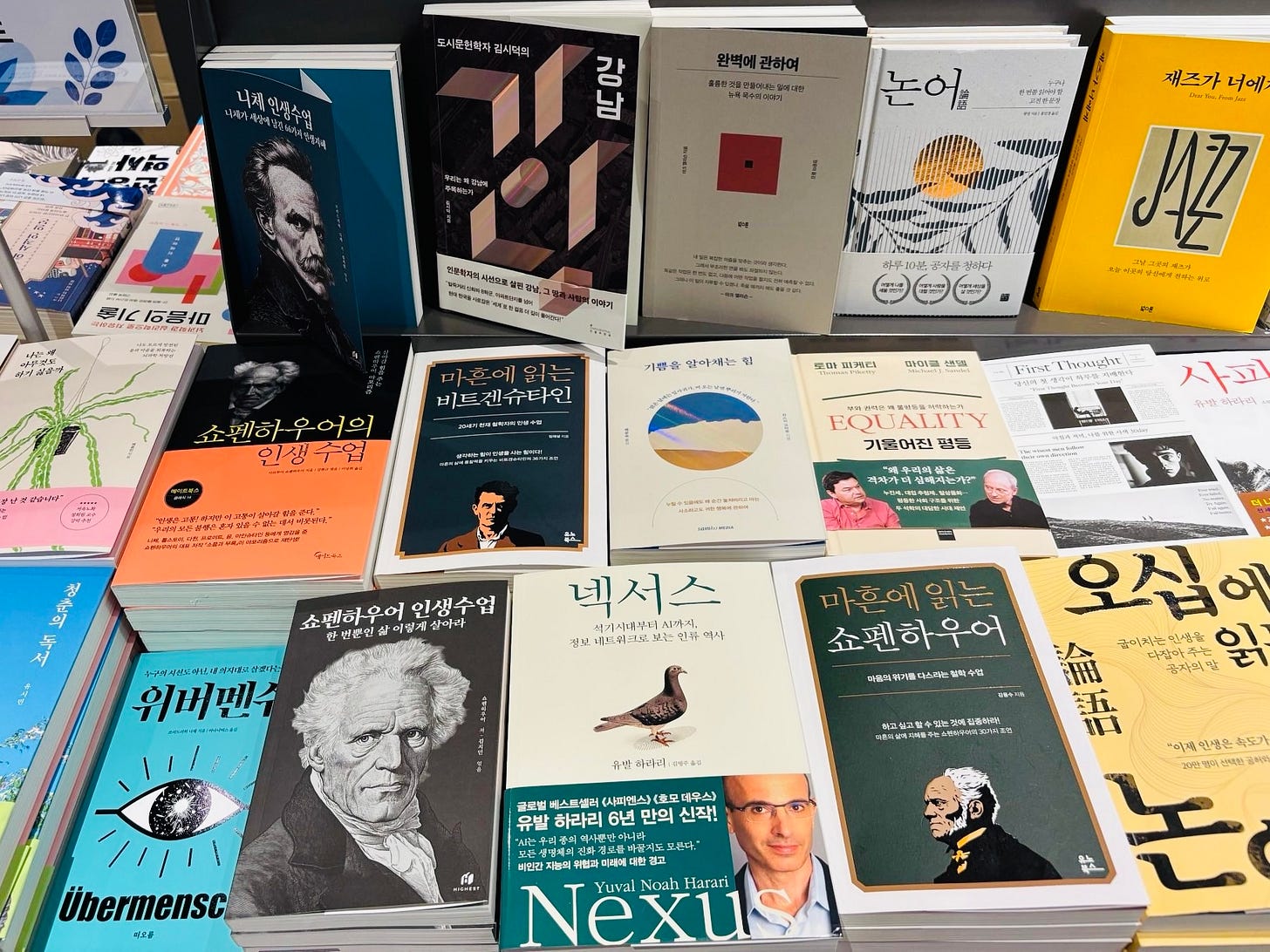

Exhibit C is from Youngpoong bookstore in Seoul. Schopenhauer makes three appearances on the feature table—his biography, Aphorisms on Practical Wisdom, and a 2023 Korean title, Reading Schopenhauer at Forty, written by Kang Yong-soo, a philosophy professor at Korea University. To the surprise of its author, the book became a massive bestseller, topping the charts at major Korean bookstores through late 2023 and most of 2024—the first philosophy title in memory to do so. It sparked what the press called a “Schopenhauer fever.” K-pop stars—many well under forty—rushed to endorse it. It appeared in an entertainment series. A dozen other Schopenhauer titles also crowd the shelves.

Exhibit C: A feature table in Youngpoong bookstore in Seoul, July 2025

VI. Lean Within

Schopenhauer’s popularity in contemporary China and South Korea may seem accidental, but it isn’t.

These are well-educated, densely networked, and hypercompetitive societies—wealthy yet grossly unequal, intellectually intense yet spiritually starved. From an early age, individuals are trained to prove their worth in the eyes of others: first through academic achievement, then through professional success, wealth, property, status, and relationships.

This model has delivered extraordinary productivity at the societal level. Cities like Seoul and Shanghai are sleeker, faster, and more technologically advanced than any Western capital. But the cost is internal. Despite outward success, many people find themselves anxious, depleted, and quietly disoriented. Beneath the shimmering surface of progress lies a gnawing sense of futility—a recognition that life, measured by conventional metrics of happiness, remains deeply unsatisfying.

Others, having achieved less, find themselves unable to escape the pressure to perform. The gap between expectation and reality—especially for younger generations facing economic stagnation and high unemployment—breeds frustration and resentment. That frustration surfaces in viral memes such as 헬조선 (Hell Joseon), a satirical term Korean youth use to liken their country to hell, or 이생망 (isaenmang, short for “this life is ruined”). According to a 2015 survey by Kyunghyang Shinmun, forty percent of young respondents said they have felt isaenmang. South Korea has the highest suicide rate among OECD countries.

China, a later developer, is faring no better. Unemployment hovers around twenty percent according to the government’s own statistics. The once-widespread belief in meritocracy—the idea that hard work and education can lift one’s station in life—has been shaken by the cold realities of economic slowdown, especially since Covid. Out of this disillusionment emerged a new lexicon: 内卷 (neijuan, involution) for zero-sum competition, 躺平 (tangping, lying flat) for refusing to participate in the competition, and 佛系 (foxi, Buddha-like) for a resigned, detached outlook. In the words of a taxi driver I chatted with this summer, people have lost “a sense of direction” (方向感).

Schopenhauer offers a philosophical outlet for this collective anxiety. He gives voice to the emotional undercurrents—the despair, the emptiness, the alienation—that many already feel but struggle to name.

Of course, East Asia is not alone in facing economic and social challenges. I don’t need to rehearse the now well-understood consequences of neoliberalism, which has left much of the world in disarray. Burnout is felt in New York as surely as in Seoul. I see the fatigue on the faces of my American students just as I see it among Chinese youth.

However, certain features of East Asian society make Schopenhauer uniquely resonant.

First, these societies have undergone what Korean sociologist Chang Kyung-Sup calls “compressed modernity”—modernization compressed into decades rather than centuries. Despite China’s official communist ideology, those familiar with the country often describe it as more capitalist than the West, marked by soaring inequality, rampant consumerism, and poor labor conditions. Compressed modernity brings high highs and low lows. It promises too much, too fast—and when disenchantment hits, it hits hard.

Compressed modernity has also left traditional belief systems—especially around family—largely intact. Older expectations clash with younger generations’ growing reluctance to marry and have children. According to World Bank data, South Korea has the world’s lowest fertility rate: 0.7 births per woman in 2023. China’s fertility rate continues to fall, even after lifting the One-Child Policy, reaching a record low of 1.0 that same year.

Second, East Asia is predominantly secular. Although around thirty percent of South Koreans identify as Christian, many—especially younger people—dislike religion’s outsized influence on politics. Among millennials and Gen Z, there is a growing belief that philosophy should replace religion. Kang, author of Reading Schopenhauer at Forty, relates in an interview: “Schopenhauer’s philosophy gives them wisdom and enlightenment instead of false comfort.”

Such “false comfort” includes not only material salves but also religious escape—epitomized by Max Weber’s “Protestant ethic”: work hard, get rich, so you can go to Heaven. Schopenhauer offers no such consolation. Unlike his contemporaries, his prescriptions require neither belief in Heaven nor denial of the empirical reality of suffering.

By framing suffering not as a deviation from divine providence but as the baseline condition of existence, Schopenhauer, counterintuitively, relieves the individual of the pressure to be happy despite unhappiness. If the world is flawed by design, then struggle and sadness are not personal failures. And who, honestly, can argue they are?

But he doesn’t stop here. Aphorisms on Practical Wisdom presents something close to a manual for living—not a roadmap to conventional success in the mold of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, but the opposite: a pamphlet of spiritual rebellion, a guide to inner freedom.

Not to Lean In, but to lean within.

Schopenhauer begins by systematically dismantling our obsession with external validation. It’s a bad wager, he warns, because these things are fragile, contingent, and beyond our control:

“The ordinary man places his life’s happiness in things external to him, in property, rank, wife and children, friends, society, and the like, so that when he loses them or finds them disappointing, the foundation of his happiness is destroyed.”

But if the foundation of your happiness is internal—your character, your mind, your intellectual wealth—then you will never be so easily disappointed:

“The wealth of the soul is the only true wealth.”

He reminds you that you don’t need these things and titles you think you need:

“Riches … are like seawater; the more you drink the thirstier you become; and the same is true of fame.”

Only philistines find “oysters and champagne the height of existence,” he writes.

In our consumerist culture, not spending money is almost always read as a symptom of poverty or as prudence—saving for future consumption. Why else would someone choose not to spend? China’s current national anxiety centers on sluggish consumer demand, widely seen as a drag on GDP growth. But in Schopenhauer’s formula, not spending is something else entirely: a deliberate refusal to participate in conspicuous consumption, a quiet act of anti-consumerist defiance.

He urges you to put your health above all else:

“Nine-tenths of our happiness depends upon health alone.”

“A healthy beggar is happier than an ailing king.”

But don’t starve, either, because:

“A man who is born with enough to live upon is generally of a somewhat independent turn of mind; he is accustomed to keep his head up.”

Having enough isn’t a license to spend or boast—it’s the freedom not to bow before those higher in the social hierarchy.

He encourages solitude over noisy socialization:

“A man is sociable just in the degree he is intellectually poor.”

This message echoes in Reading Schopenhauer at Forty. As Kang said in an interview: “Schopenhauer tells us that people often fail to productively utilize their solitary time due to incapacity, inner emptiness, and boredom. In such cases, socializing with others is a cowardly way of avoiding confrontation with one’s own solitude.”

But if you live a rich inner life, you may come to prefer the lasting joy of solitude. This sentiment speaks to those with what some call “relationship fatigue.” Single-person households have steadily risen in wealthy countries, nearing fifty percent in Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. Japan, South Korea, and China are not far behind, with rates approaching thirty percent. In East Asia’s densely networked societies, many feel an urge to step back—to loose themselves from the tight weave of social and familiar ties and the weighty expectations that come with them.

He tells you what others think of you could hardly matter less. He couldn’t understand why people crave praise:

“If you stroke a cat, it will purr.”

But if you truly grasp “how superficial and futile are most people’s thoughts, how narrow their ideas, how mean their sentiments, how perverse their opinions, and how much of error there is in most of them,” you’ll stop caring.

This need to stop caring is keenly felt—but hardly easy. Social media subjects young people, especially young women, to punishing beauty standards, leading to rising rates of teen depression and suicide around the world. East Asia is especially known for its exacting ideals of appearance. And yet, something is shifting. In South Korea, a rebellion against K-beauty is underway: the rise of the no-makeup movement. My favorite discovery while researching this essay was a hashtag making the rounds: “Schopenhauer-style makeup,” which means, simply, going without makeup. (The irony is that some end up spending even more time applying makeup to look makeup-free.)

To those annoyed by rising hypernationalism, which is no stranger to China and South Korea, Schopenhauer offers a cold splash of clarity:

“The cheapest sort of pride is national pride.”

Only those with little to take pride in themselves cling most tightly to the nation. By contrast:

“The man who is endowed with important personal qualities will be only too ready to see clearly in what respects his own nation falls short.”

“Every nation mocks other nations, and all are right.”

To those who, like his younger self, longed in vain for fame, he offers a final consolation:

“People are more likely to appreciate the man who serves the circumstances of his own brief hour, or the temper of the moment.” (That would be Hegel.)

“The more a man belongs to posterity, in other words, to humanity in general, the more of an alien he is to his contemporaries.” (That would be himself.)

Which is why, he noted, “contemporary praise so seldom develops into posthumous fame.”

Alas, that curse did not work on Hegel.

In the end, Schopenhauer’s message is disarmingly simple: happiness comes from within, not without—“not through society, but in spite of it.”

This is his reconciliation, with himself, with the “failures” meticulously recorded in his diary, and with a society he never truly felt part of. That same sense of mismatch, of being fundamentally out of step with the world, has become the generational mood among today’s youth. The structures their grandparents built—which more or less held up for their parents—no longer serve them. Increasingly, they ask: Why follow the script if I never stood a chance to begin with? They have again entered existential territory, where the oldest question awaits: Why is life worth living?

In one corner of the world, people are finding intellectual salvation in a message at once sobering and liberating: life is indeed worth living—but only once you stop pretending your pain isn’t real. That it’s your fault you’re not drowning in cash or surrounded by crowds. That if you just leaned in harder, bought the house with the white picket fence, and raised the kids who get into Harvard, you’d finally be happy. You won’t. You’re barking up the wrong tree.

Mann said that Schopenhauer’s pessimist humanity “herald[s] the temper of a future time” (Mann 1939, 30). The time arrived in the late-nineteenth century, crystallizing in post-WWII Europe, and it has come again.

Schopenhauer, Safranski writes, is “the philosopher of the pain of secularization, of metaphysical homelessness, of lost original confidence” (Safranski 1991, 345).

VII. Bible for the Educated Bourgeoisie

In 1851, at sixty-three, Schopenhauer published Parerga and Paralipomena (Appendices and Omissions), a sprawling collection of essays on everything from color theory to suicide. Among its contents is “Aphorisms on Practical Wisdom”—the very text now lining bookstore shelves across East Asia. (The same volume also contains some of his more troubling views on women, which are too cringeworthy to mention here without another six thousand words, and which his critics have rightly not ignored.)

At last, the audience Schopenhauer had secretly hoped for in his youth found him. (What was to become) Germany in 1848 was not the same as (what was to become) Germany in 1818. The failed revolutions of 1848 left much of Europe steeped in disillusionment and introspection. Post-French Revolution optimism had faded. The grand idealism of Hegel, Fichte, and Schelling no longer matched the mood of the age. In contrast, Schopenhauer’s philosophy, with its unflinching exposure of the irrationality and absurdity of existence, resonated with the public. His prose—elegant, clear, and brutally direct—stood apart from the dense abstractions of the Idealists. Aphorisms on Practical Wisdom quickly became “the Bible for the educated bourgeoisie” (Safranski 1991, 334).

In Chinese, there is a term for “exiting the circle” (出圈, chuquan). It refers to work that breaks beyond the creator’s original professional sphere and reaches a broader public. Schopenhauer’s writing—utterly free of academic pretension and pedantic indulgence—did just that. His thoughts traveled far beyond the bounds of philosophy, leaving its mark on artists, writers, musicians, and scientists alike.

In his autobiography, Carl Jung (1875-1961) called Schopenhauer a “great find” from his early readings:

“Here at last was a philosopher who had the courage to see that all was not for the best in the fundaments of the universe.”

Schopenhauer would have been delighted to learn that Jung was “put off” by Hegel, and regarded him “with downright distrust” (Jung 1963, 69).

In 1869, as Tolstoy was finalizing War and Peace, he found himself procrastinating with The World as Will and Representation:

“Do you know what this summer has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of spiritual delights which I’ve never experienced before.” (Tolstoy 2015, 221)

Mann compared his first encounter with Schopenhauer at the age of twenty to the “organic shock” of love and sex.

Schopenhauer’s shadow looms over late 19th- and early 20th-century Western art and literature. It’s the irreconcilable tension between bourgeois convention and aesthetic yearning in Buddenbrooks; the doomed longing between Tristan and Isolde; the vast, indifferent, and inscrutable ocean of Moby-Dick; the thin veneer of civilization peeled back in Heart of Darkness; Marcel’s soul-searching reveries In Search of Lost Time; the invisible hand that pushes Anna Karenina in front of a train.

In all these works, despite their darkness and underlying pessimism, we feel the “strange, deep satisfaction” that Mann felt upon reading Schopenhauer:

“Everyone feels this satisfaction; everyone realizes that when this great writer and commanding spirit speaks of the suffering of the world, he speaks of yours and mine.” (Mann 1939, 11)

VIII. Philosophy for the World

By the time fame finally found him in his sixties, Schopenhauer had been living quietly in Frankfurt with his beloved poodle for two decades. He had left Berlin in 1831 to escape a cholera outbreak—the very epidemic that claimed Hegel’s life. Would he have stayed in Berlin if his academic career had taken off? Did he feel any pang of loss at the death of his intellectual nemesis?

If he felt any grief, he didn’t show it. He continued attacking Hegel with the same relish in death as in life.

“This Hegel, who was proclaimed by the University to be a great philosopher, was a clumsy, inarticulate, and disgustingly ugly fellow … an empty-headed blockhead and an intellectual fraud.” (Ouch.)

“The whole of Hegel’s philosophy is a monstrous mystification, which will one day be recognized as a stupendous hoax, a permanent monument to German stupidity.”

That “permanent monument to German stupidity” now towers outside my apartment in central Berlin.

I don’t mind Hegel—except for that one much-abused, reactionary line “What is rational is real; what is real is rational.” I’ve heard it used to justify everything from political repression to environmental collapse.

Truth be told, I like Hegel: the dialectical method he refined, the foundations he laid for critical theory. And sometimes, when the world feels especially bleak, I take comfort in his end-of-history teleology. Who doesn’t indulge in a little wishful thinking now and then?

But more often than not, one grows nauseated, like Schopenhauer did, by blind idealism, by teleology, by jargon, by narratives so grand they sound neither real nor rational. To Jung, Hegel “was caged in the edifice of his own words and was pompously gesticulating in his [own] prison” (Jung 1963, 69). Where there is a cage of reason, there is always a mind wrestling to break free.

In contrast, Schopenhauer offers something more enduring: what he called “philosophy for the world” (and what Russell dismissed as not real philosophy)—a meditation on the universal conditions of suffering, desire, and the search for meaning. He makes space for those who wish to say no to unexamined striving; to retreat—but not escape—from society and its clamor; to dwell with flowers, animals, and music; to give themselves to neither suicidal despair nor utopian delusion. It turns out, there are many of them.

IX. Deb

My friend Deb has never read Schopenhauer, nor has she any interest in the solitary, philosophical life he extolled. And yet, she might as well be an embodiment of “practical wisdom.” After getting her Ph.D. in 2018, she devoted herself to teaching and advancing policies prioritizing the common good over narrow nationalist agendas.

Navigating the treacherous waters of contemporary U.S.-China relations, she never sinks into despair or drifts into idealism. She avoids easy binaries, never speaking about good versus evil, or us versus them. She has no patience for bullshit: be sure you know what you’re talking about when talking to her. Because if you don’t, she will set you straight.

And she keeps moving forward. While I holed up at home, drowning in 19th-century German philosophy, Deb was in the world, touring factories and studying clean energy production in China.

And she never stops living. In July, she visited me in Hangzhou. Over tea by the storm-kissed waters of West Lake, we debated which color Labubu to bring home for her daughter. In that entirely unremarkable moment, it struck me: there is so much to live for in the world without, as there is in the self within.

Bibliography

App, Urs. Arthur Schopenhauer and China: A Sino-Platonic Love Affair. University of Pennsylvania, 2010.

Chang Kyung-Sup. The Logic of Compressed Modernity. Cambridge: Polity, 2022.

Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage, 2012.

Jung, Carl G. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Edited by Aniela Jaffé. Translated by Richard and Clare Winston. New York: Vintage, 1963.

Kang Yong-soo. Reading Schopenhauer at Forty [마흔에 읽는 쇼펜하우어]. Seoul: Uknowbooks, 2023.

Mann, Thomas. Schopenhauer. Edited by Alfred O. Mendel. Philadelphia: David McKay Company, 1939.

Russell, Bertrand. A History of Western Philosophy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1945.

Safranski, Rüdiger. Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy. Translated by Edward Osers. Harvard University Press, 1991.

Schopenhauer, Arthur. Parerga and Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays (Volume 1). Translated by Sabine Roehr and Christopher Janaway. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Schopenhauer, Arthur. The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer; The Wisdom of Life. Translated by T. Bailey Saunders. Middlesex: The Echo Library, 2006.

Tolstoy, Leo. Tolstoy’s Letters (Volume I: 1828-1879). Selected, edited, and translated by R. F. Christian. London: Farmer & Farber, 2015.

Wicks, Robert. “Arthur Schopenhauer,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2024 Edition). Edited by Edward N. Zalta and Uri Nodelman.

Follow up to my post: Professor Ding must know of her colleague formerly at Northwestern, now at U. of Chicago, Dr. Brook Ziporyn, whose works on Chinese philosophy, Chinese Tiantai Buddhism, and Daoism interpret and present the vast span of Chinese philosophical wisdom in English. I can highly recommend his "Emptiness and Omnipresence" and "Being and Ambiguity," - books for the philosophically inclined. See my (Blaine Snow) reviews of these books on Goodreads.com or on Academia.edu.

This essay blew my mind - SO insightful, instructive, revealing, and wise. I've read much about Schopenhauer and also know Urs App's work on the influence of Asian philosophical systems on western philosophers (see App's 2010 "The Birth of Orientalism"). I also learned about Schopenhauer's influence on Wagner and later on Nietzsche through Brian Magee's book "The Tristan Chord."

Having been an ESL teacher for 38 years working mainly with East Asian college students from Japan, Korea, and China, Ding's insights into their compressed modernity malaise and emptiness wasn't surprising - I could see this going on 20 years ago. But it's clearly been greatly amplified with the intensification of modernity.

I'm also a lifelong student of Buddhism and have amassed hundreds of volumes on Indian, Tibetan, Chinese, and Japanese forms of Buddhism. Knowing as I do the richness, depth, and sophistication of the Buddhist tradition in these countries makes me sad to think that these young people look to a western philosopher, Schopenhauer, to teach them about their OWN TRADITIONS when they should be immersed in centuries of their own Buddhist wisdom that Schopenhauer, frankly, didn't represent very well, or at least only very thinly.

No doubt Asian youth have been soured on their own wisdom traditions in the same way westerners have been soured on western religious traditions which is super sad because philosophical Buddhism is a thousand times richer than anything Schopenhauer ever produced. Traditions in Japan, Korea, and China are unbelievably diverse, refined, nuanced, argued, developed with thousands of volumes of wisdom texts to be discovered. It's a shame the great works of their own traditions are still lost to them... Chan/Zen tradition, Tiantai and Huayan Buddhism of China, Chinese Daoist tradition, Chinese Neo-Confucianism... fantastically rich, centuries of literature, hundreds of philosophers, sages, poets...

Thanks again to Iza Ding for one of the best essays on East Asian culture I've ever read.