Taiwan's Democratic Election and China's Democratic Hopes

Does Taiwan's successful election prove that democracy is possible for China? Yes. But so what?

Last month, Taiwan held its election, and nothing terrible happened. William Lai Ching-te, the candidate of whom Beijing was none too fond, won with a plurality of votes. In the weeks that followed, Beijing rattled the sabers without much conviction, consoled itself with the results in the Legislative Yuan, and with relatively minor diplomatic victories that deprived Taipei of two more countries with which it, until recently, still had formal ties.

Meanwhile, much of the rest of the world celebrated what was, by any objective reckoning, a model democratic election. One essay that did so in The Guardian received a lot of praise, and understandably: I thought it was very well-written and captured the pride that a lot of people felt — especially in Taiwan, where the author was writing from — in the immediate aftermath of the election. (That author, Michelle Kuo, is no relation — but happens to share not only a surname but one more character of her Chinese name with me, my siblings, and my paternal first cousins. Kinda neat!)

Kuo’s essay made one point that was singled out, quote-tweeted, and “liked” by quite a number of people who study China. It’s a point that many have made before: that Taiwan’s arrival as a full-fledged democracy, with competitive, free, and fair elections all the way up to the highest executive level, thoroughly discredits the claim that something in Chinese culture is inherently inimical to democracy.

Ignoring, for now, the claim that Taiwan can be understood simply as an instance of a polity with Chinese culture — there are, I’m sure, people who might take issue with that — I don’t hesitate to agree with the basic assertion: No one can or should claim that Chinese culture and electoral democracy are fundamentally incompatible.

My problem with this is that it’s something of a straw man. Yes, there are some people — people within China’s Communist Party, people who support its form of government both inside and outside of China — who have made claims along those lines and perhaps still do. But those people are relatively few: so few, indeed, that I don’t think they’re worth targeting. The issue I have with the claim is the likelihood that it will be deployed against a bigger, far more common claim: That there are elements in Chinese culture as it exists today that make it more difficult in China for democracy to take root and to flourish than it was in Taiwan.

After waiting a long time, many were nonetheless deeply disappointed.

I don’t know whether the author considered this issue, and I suppose there’s no reason she should have been obliged in any sense to do so: her claim, as printed, is true.

But If I were to write that this plane that I’m now on, midway over the Atlantic, proves that traveling at 926 kilometers per hour in a metal vessel weighing close to 200 metric tons, at an altitude of 11,0000 meters is entirely possible, that claim would also be true.

I wouldn’t expect to be challenged on it. It would have been true even were I to, say, travel back a century in time with irrefutable evidence that I’d come from the future and that in the year 2024, we routinely fly across the Atlantic with several hundred others aboard, and pay perhaps a week’s wage for the privilege, return trip included. Doing so would certainly prove wrong those doubters of 1924 who insisted such a thing could never be. It might even give some — a Charles Lindbergh, an Amelia Earhart — inspiration or hope, or banish any feelings of futility they might have.

But that wouldn’t make the achievement easy. It wouldn’t change the fact that engines that powerful didn’t yet exist — as of 1924, jet propulsion as an idea had already been around for centuries but had never actually been used in flight — and that many pieces would still need to be put into place before people would be crossing the Atlantic a thousand at a time, thousands of times a day in just six hours.

My point isn’t that China is politically a century behind Taiwan. It’s that this tendency to point to the success of democracy in Taiwan to demonstrate the People’s Republic of China’s moral failure for not implementing electoral democracy is simplistic and misleading. It too readily dismisses an argument about necessary conditions for successful democracy that has by no means been settled. The maximalist position — the claim that China’s political culture is intrinsically and immutably hostile soil in which democracy will never grow — is not the argument being made by any serious people.

Even during the height of the “Asian Values” debate in the 1990s, when the conspicuous success of the Asian Tigers and their transition away from authoritarianism raised the question of whether China would follow that same path, it was rare to hear anyone making the case that something about Confucianism, or China’s political culture, simply ruled out a democratic future for the PRC.

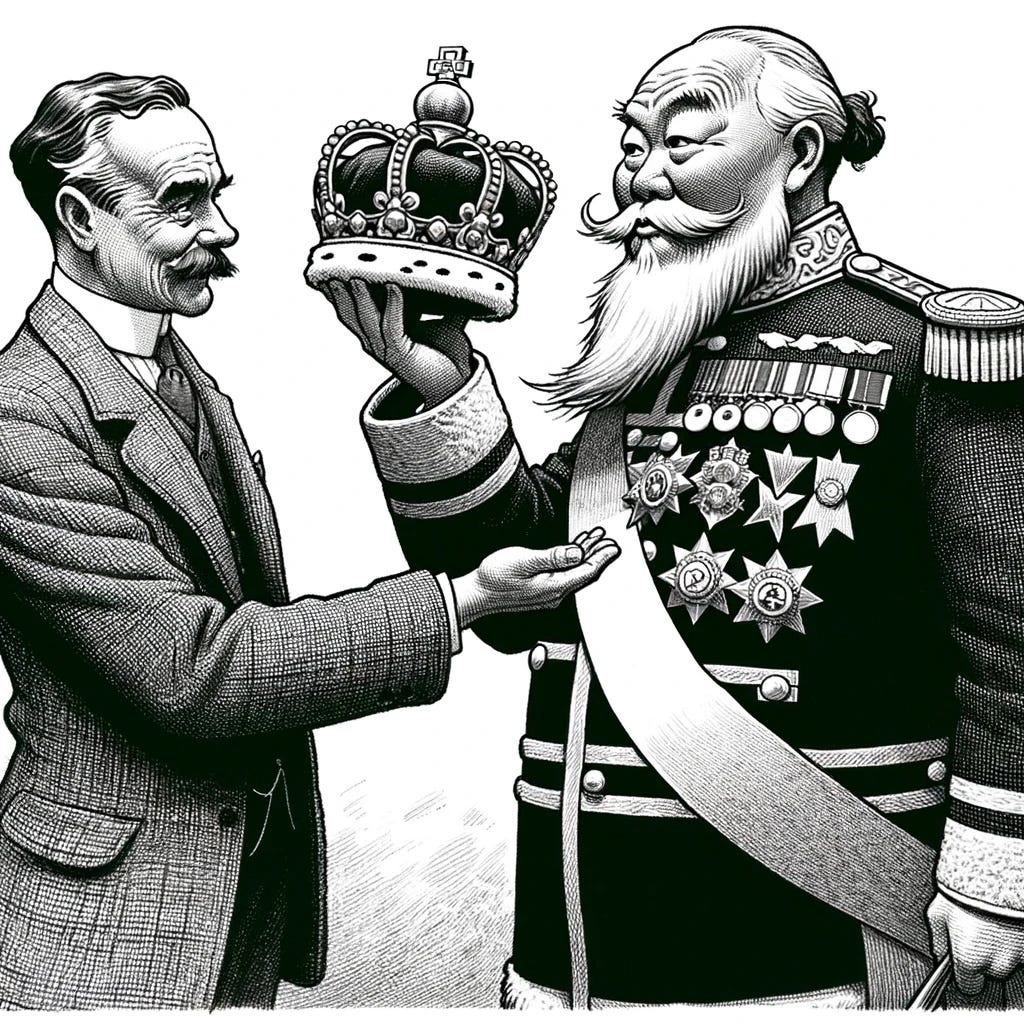

This debate is much older, of course: it was hotly debated both before and after the 1911 Revolution, throughout the May Fourth period. Yuan Shikai, the ex-Qing general who commanded the Beiyang Army and muscled his way into a provisional presidency and decided first that he was unhappy with merely “provisional,” then with merely “presidency,” was famously convinced by the Columbia political scientist Frank Goodnow, one of his advisors, to declare himself emperor because of Goodnow’s conclusion that the Chinese people weren’t “ready” for democracy. That proved disastrous for China — and for Yuan, who died just months after assuming the purple.

.

Even that infamous forerunner to “Asian Values” didn’t assume that the Chinese people would never be ready. Sun Yat-sen, from whom Yuan first wrested that presidency in 1912, believed that China would first need to undergo a period of “tutelage” during which the Chinese people could be taught democratic values. Full democracy would have to wait. When the Kuomintang reorganized in the early 1920s, it was as an explicitly Leninist authoritarian party. At least until Chiang Ching-Kuo took over the presidency from his unalloyed authoritarian of a father in 1976, tutelage — though formally part of KMT ideology — was relegated to the back burner.

Were there factors that gave Taiwan a boost? I suspect that yes, there were. Its relatively small population, the education level of both Taiwanese who had lived under Japanese occupation and the Waishengren who followed the KMT into exile, the substantial hard currency reserves that Chiang Kai-shek’s government brought with it from China, the protection afforded Taiwan after the Korean War by U.S. forces, the receptiveness of the U.S. beginning in the 1950s to Chinese students (among whom were my parents), as an export market, the openness and low tariff barriers to Taiwan’s manufactured goods — these all may have been factors that accelerated the transition. Where any of these conditions find parallels with the PRC, they only came decades later.

But we can’t say with any certitude which, if any, of these favorable factors actually mattered. The fact is we simply don’t know what conditions need to be satisfied in order to have democracy. Some might say, after the great May Fourth luminary Hu Shi, that “the only way to have democracy is to have democracy.” For a very long time, it was a widely-held belief that democratization would follow naturally once a given country developed a middle class of some critical mass and critical level of income. Has that idea — the essence of “modernization theory” — been really put to rest by the Chinese counterexample? I’m not actually sure.

What about size? Does that have anything to do with it? Perhaps. Is India proof that size doesn’t matter? Again, perhaps — though whether the democratic experiment has succeeded or failed in India remains a matter of debate. What about Indonesia? Another populous, very diverse country that hasn’t attained anyone’s magic threshold of per capita GDP, yet democracy seemed — at least prior to the current juncture — to be succeeding What accounts for democratic backsliding in Poland, or Hungary — or God forbid, the United States itself?

I hope we can all agree that it didn’t really take Taiwan’s successful elections — not in 2024 or in any of the seven preceding contests — to prove that maximalist claims about some unchanging, eternal Chinese political culture that forecloses any possibility of electoral democracy ever putting down roots are just nonsense. But I also hope we can agree that leaping to the opposite conclusion is equally silly: That political culture is infinitely and instantaneously malleable, and that we can safely ignore factors of demographics, resource endowment, education and literacy, urbanization rates, wealth and income and the distribution thereof, the security environment, alliances and foreign relations — and of course history.

There are two main lines of argument that, in my twenty-odd years in China, I heard repeatedly among my friends and acquaintances whenever the subject of democratic transition was raised. I’d be surprised if anyone reading this who had spent much time in China at all over the last three decades hasn’t heard them both. They were raised by intellectuals and hard-drinking rockers alike, by colleagues in tech companies, by earnest Party members and, yes, even cab drivers. The first is what you might call the 素质 sùzhì argument: that the “personal quality” or the “character and breeding” of Chinese people just wasn’t at a sufficiently high level to make democracy work in China. One columnist for an English-language newspaper in China, who had lived in Silicon Valley for several years, said to me during the early 2010s, “If we held elections right now, we’d elect Hitler and be at war with Japan by next Tuesday.”

The other argument is the familiar chaos argument: “中国人怕乱 Zhōngguórén pà luàn,” one often hears: Chinese people fear chaos. There’s a living memory, as this one goes, of the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, of the Civil War, even of the Warlord Period — periods of social and political breakdown, of anarchy. Jeremiah Jenne, an American historian who’s lived in China for well over 20 years (though not for much longer!) said it best, and probably better than this paraphrase: “When Americans create their movie villains, they’re always some version of the Nazis, the SS, jackbooted thugs — think of Star Wars, where the footsoldiers of the Empire are literally called Stormtroopers. The fear is of authoritarianism run amok. But for the Chinese, it’s an absence of authority: it’s chaos, or luan.”

Many would detect that a racism of low expectations is at work in the suzhi argument, and it could well be there. It’s a pessimistic take, to be sure. But neither claim contains an explicit assumption that democracy will forever be impossible. Rather, what both suggest is that were certain conditions to be met — that suzhi level raised, that luan far enough back in memory — then it could very well take root.

The two arguments were combined, it now occurs to me, in one half-joking utterance by a Chinese-American journalist who worked for an American network for many years in China. Jeremy and I had just finished taping an episode of Sinica with her in that grotty old apartment where we used to record in Beijing many years ago, and we each grabbed a beer from the fridge. “If China ever stops being a police state,” she said, cracking hers open, “I’m getting the hell out of here.”

Rather than asking the abstract question of whether democracy would ever "work" in China, a more interesting question to me is whether we think governance in better on the mainland under authoritarian rule, or better in Taiwan under a functioning democracy. Which of the two set of politicians are trying to implement policies that will lead to better long term future for the people and which are trying to put up the best show for the next poll ? Authoritarian rule comes with negatives -inhumane quarantine rules, persecution of members of the free press and anyone with political ambitions that does not fall under the control of the Party are but a few examples. But it also comes with many achievements, mostly economical but also in the culture of the population. Many people will agree with me that you don't feel everyone is trying to cheat you while travelling through China nowadays (even in rural areas) which was not the case until quite recently (including the Hu-Wen era). I would argue that more political control under Xi has somehow led to a population that behaves with more civility towards each other. Whether that is a "good trade" is up for debate.