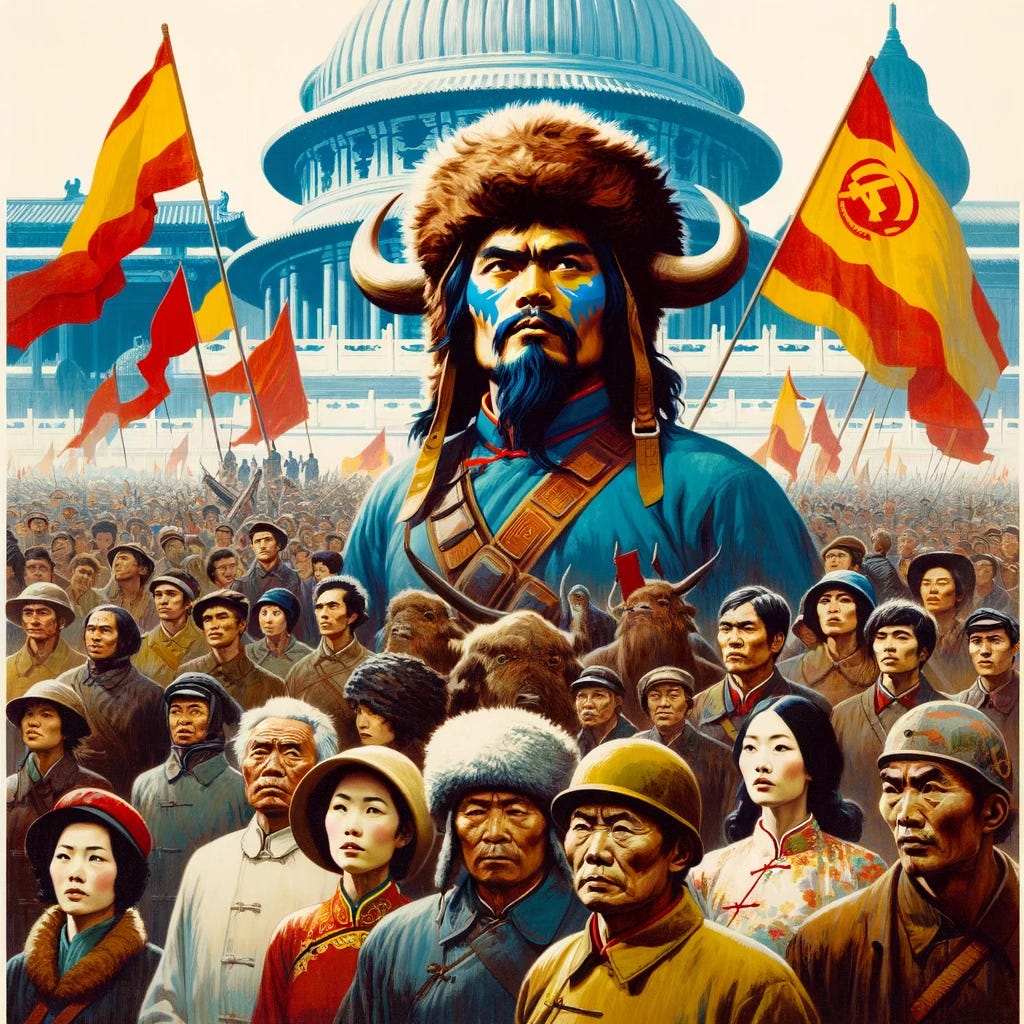

The Cultural Revolution and the Three Body Problem

I dreaded the release of Netflix’s adaptation of The Three-Body Problem.

My foreboding over its debut had nothing to do with the decision by showrunners David Benioff and Dan Weiss to change up the nationalities of so many characters — for Chinese viewers, doubtless the most controversial decision, and the focus of much ire even among viewers outside of China.

For me, it was the Cultural Revolution sequence at the story’s beginning. It’s there, of course, in Liu Cixin’s original novel — though not at the beginning in the original Chinese text, where it only comes a few chapters in. The English translation, though, opens with it, apparently in keeping with Liu Cixin’s original intention. Integral as it is to the story’s plot, there was no way it wouldn’t feature prominently in the Netflix version too: It is, after all, the trauma that ignites the hatred for humanity the story’s complicated antagonist, Ye Wenjie, harbors. And just as her solar-amplified radio message aimed at Alpha Centauri was bound to set off an invasion of Earth by the Trisolarans — the “San-ti” of the Netflix version, the depiction of her father’s persecution during the Cultural Revolution on America’s most popular streaming platform was almost certain to set off a torrent of ignorant commentary invoking the Cultural Revolution to make inane claims about American or Chinese politics. And it did.

Comparisons came in two basic and predictable flavors: Wokeism and cancel culture are the Cultural Revolution come to America; and China under Xi Jinping is the Cultural Revolution come back to China. I hope soon that some new internet law akin to Godwin’s famous dictum will address the lamentable propensity to make specious comparisons to the Cultural Revolution that trivialize the horrors of one of China’s darkest chapters.