The Spring & Autumn Annals, Part 1

Just hours before publishing this, I learned of the passing of Ozzy Osbourne, who was a figure of towering influence in my metalhead youth. My bandmates and I had all watched many clips of his farewell performance just weeks ago in his native Birmingham, attended by rock royalty and culminating in the final Black Sabbath show. On behalf of all my bandmates, I salute you, Ozzy. Thank you for all that you’ve done for Metal music, and extend my deepest condolences to your wife and children. May you rest in rock.

Most mornings in Shaxi, I was the first one up. I’d pad down the rough wooden plank stairs of the Flower Inn, fire up the espresso machine, and scramble up a couple of eggs with diced Yunnan ham and some chopped scallions on the wok burner in the guesthouse kitchen. Outside, the garden would still be wet with dew, the goldfish barely stirring in their winding pond, and the peaks across the valley still hidden in mist.

Sometimes Li Meng, our keyboardist and also an early riser, would already be at his instrument in the main room, headphones on, lost in some intricate passage. As I walk down the hallway from the stairs, I often pause for a moment just to watch. The only audible sound would be the faint thud of his fingers on the keys — a kind of percussion with no tone — but his face would be entirely absorbed, brow furrowed or sometimes slack with concentration, as if he were hearing something vast and luminous in his head. It was like watching someone speak in a dream, full of urgency and meaning, but just out of earshot.

I didn’t come here to escape anything, really — just to spend a month making music with old friends, away from the noise and churn of daily life. It’s been nearly thirty years since I last gave this kind of time and attention to music, when I came back to China in 1996 and rejoined my earlier, better-known band. That felt urgent, even a little desperate: the bassist Zhang Ju had died the previous year, and the band was on the verge of a breakup. This time, it feels simpler. We came to this quiet town in Yunnan not to relive anything, but to see what might still be possible.

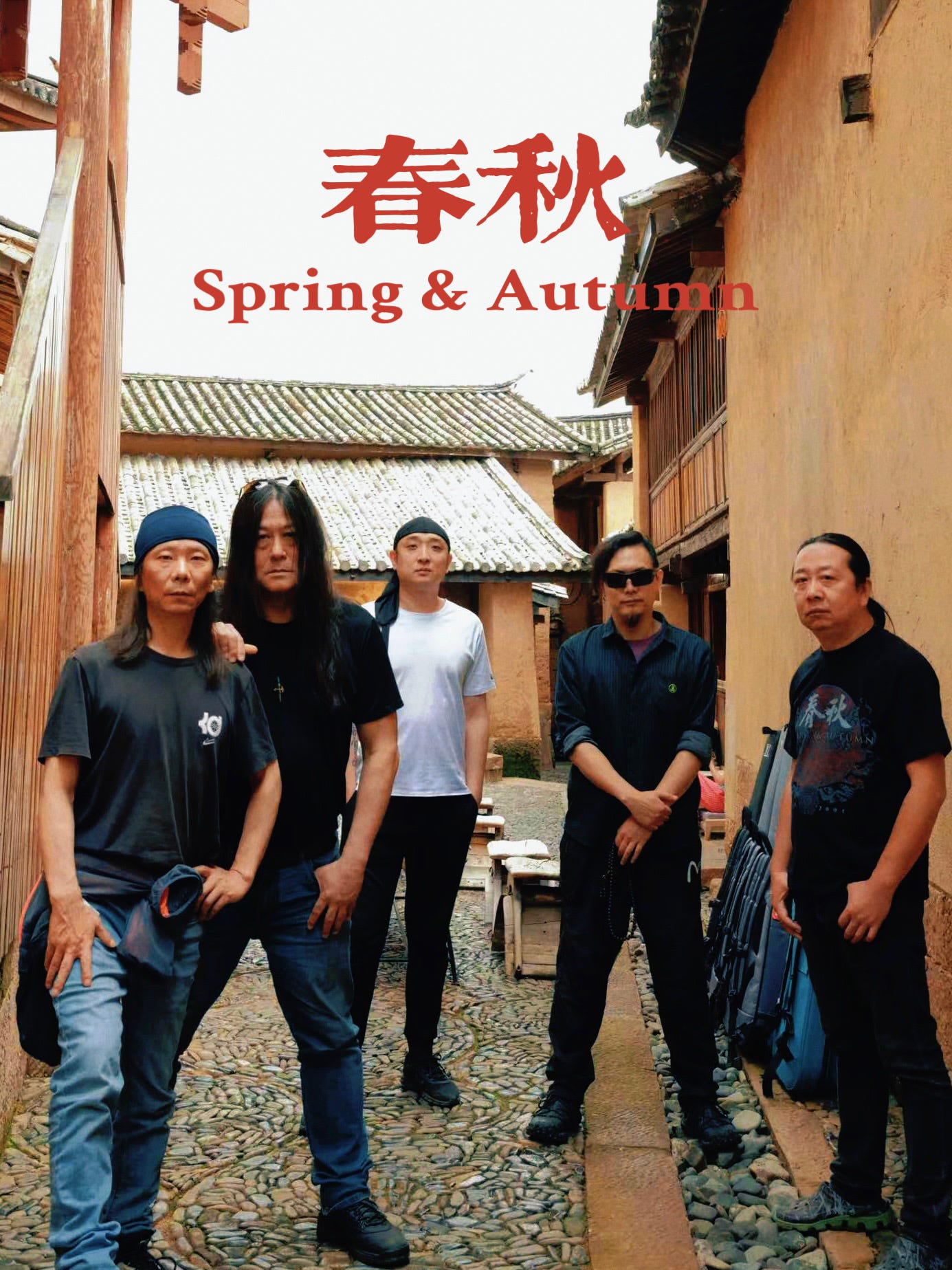

A year ago, I had come back to China for the first time since the COVID epidemic and reconnected with my old bandmate from Spring & Autumn, Kou Zhengyu. He convinced me then that we should try to put the band back together for a reunion show at some unspecified date — probably the annual metal festival he runs, the 330 Metal Festival, in March of 2025, when we could at least be assured a berth. He planted the seed with me.

Back in Chapel Hill, I restrung my guitars, built myself a new pedalboard, and began shaking off the accumulated rust of effectively eight years of no serious playing. Then, back in Beijing in October, Xiao Kou and I spent considerably more time together. I bought a new guitar: a Paul Reed Smith Custom 24 (a “ten-top,” if that means anything to you — lovely flame maple top!), and played it constantly.

Confident by then that we could pull it off, we reached out to the other bandmates: First, naturally, to Yang Meng, our singer, lyricist, and my main songwriting partner, who had left Beijing long ago and had been living in his native Yunnan; then to Li Meng, who had quit the police force back in 2011 and was now making a living as a composer, librettist, and director of musical theatre; Song Yang, our bassist, who was teaching at Beijing’s Midi Music School; and (our old drummer having moved to Los Angeles) Wu Gang, who would join us on drums: he had, after all, told Xiao Kou many times that should Spring & Autumn ever reform, he simply had to be the drummer.

And so the plan for a reunion show was hatched. The hard part was convincing Yang Meng to come back to Beijing, where the cost of living is relatively high and — now having been to Shaxi, where he’d been living — the pace of things is, by comparison, so hectic and rushed. I began planning for another trip to Beijing for March and April of 2025, and meanwhile, put in three or four hours a day of intense practice to get my chops and my callouses back. Yang Meng flew to Beijing and arrived a couple of days after I got there, and we managed to get in five full-band rehearsals of our old material ahead of our big show.

Before we’d even finished the first of these rehearsals, it was clear that this wasn’t going to be just about a one-off reunion show. Nearly nine years had elapsed since we had played our farewell show at Yugong Yishan in Beijing at the end of May 2016. But despite the long hiatus, it was clear that we all still had it. We were surprisingly tight, made few mistakes, and it almost went without saying that Spring & Autumn was back. And before we even played the 330 Metal Festival, we had said yes to another show in early April in Yantai (Shandong), and we were already writing new material and planning the direction of the next album.

Yang Meng had floated the idea of a summer retreat in Yunnan — it was something he more or less demanded, since we had, after all, pulled him away from his home province to spend a month in Beijing — and plans firmed up quickly. He picked, as it turns out, the perfect spot for us: Shaxi, and the Qiangweihuakai Guest House. Astonishingly, everyone but the drummer was able to commit to a month. And in the months leading up to my flight back to Beijing in June, there was an intense flurry of back-and-forth on WeChat: riffs and melodies, then whole song structures, and then multitrack demos we all contributed to remotely, from Yunnan, Beijing, and Chapel Hill. We had sketches of seven songs completed before any of us even arrived.

The Qiangweihuakai Guest House — its English name, “Flower Inn,” would be more accurately rendered as “The Rose in Bloom” — is in Xiao Changle Cun, a charming village on a slope surrounded by fields of tobacco, corn, and, sundflowers, and beans, with a few rice paddies down the hill where the land levels out. It’s just 700 meters or so to the west of the old town of Shaxi, and it overlooks the valley dominated by that ancient waystation on the Tea Horse Trail.

Outside the compact little guest house is a tidy garden full of fruit trees, Japanese maples, and wild roses — the 蔷薇花 after whose blooms (alas, whose glory is revealed only in March and April) the hostel is named. It has a canvas-covered mini veranda with a picnic table beneath it and a brick fireplace beside it. There’s a little patch off to one side where the owners grow herbs and vegetables. There’s a cheerful Golden Retriever named Maomao with an odd fixation on plastic water bottles, two miniature poodles, Shishi and Momo, as well as a couple of cats who wander in and out.

The guest house itself, painted a cheery ochre and largely free of the excessive, altogether too-precious traditional architectural flourishes to which the inns in town are given to indulge, is quite spartan within. The floors are bare concrete, the walls thinly plastered and painted a dusty gray, but the place still gives off a welcoming vibe, especially if you’re a bunch of musicians intending to make the place your temporary rehearsal space. The main room was clearly set up with musicians in mind: against one wall is an electric piano, and when we arrived there were a couple of guitars on a multi-instrument rack, a generic electric bass and a little Hardtke bass amp, and a serviceable music stand. A decent violin and well-rosined bow was hanging on one of the painted brick pillars: the owner plays rather nicely.

There’s a fridge full of beer, apple juice, and yogurt, and an excellent espresso machine which I’ve availed myself of several times a day. The insanely well-stocked kitchen is available for us to use, and as I seem to be the first person up every morning — the couple who owns the place are night owls, up playing cards or singing karaoke until quite late on many evenings — I’ve been making my breakfast of scrambled eggs there on a crazily powerful wok burner. One morning a few days after we arrived, Yang Meng, the band’s singer who spends much of the year here in Shaxi or in nearby Dali, headed up into the mountains for some hiking with his girlfriend Yanlan and her eight-year-old son and returned with a basketful of wild mushrooms that he then cooked up for dinner.

It’s quite a perfect arrangement, and all of us who arrived on June 21st were delighted with Yang Meng for having found such an ideal place. It’s cheap, too: RMB 2000 yuan for the whole month for each of our rooms — and all that free coffee, food, beer, and more. Spring & Autumn has taken over the entire upper floor, and our rooms are spacious and, if spare, nevertheless comfortable. With the exception of one guest, a pleasant Cantonese cycling enthusiast who studied at UCLA and was reading The Kite Runner in English when I met him, and who earns his living now as a day trader, the rest of the people living in the guest house are relatives of the owners. They all hail from Ningxia in China’s Northwest, and the members of this clan, with its various in-laws and cousins, all in their 30s and 40s, are big-hearted folk to a one. One evening last week they threw a big barbecue bash occasioned by the arrival of one relative bearing what must have been 15 kilos of excellent lamb from their native Ningxia (which, being from Ningxia, as we were told a dozen times by various of the clan, “doesn’t have that gamey taste.”) We stuffed ourselves with lamb skewers, generously sprinkled with cumin and chili powder, and with other delicacies, and then that night, after an abbreviated rehearsal, we began spontaneously to play through our repertoire of Chinese rock classics — songs by Beyond, Cui Jian, Black Panther, Overload, and of course, Tang Dynasty — that stretched on until 2 am.

Astonishingly, these folk seem not to mind our rehearsals at all, though I know I’d be heartily sick of the same several songs to which they were ceaselessly subjected. We’ve decided to keep our rehearsals to the hours of 10 am to 1 pm, then a lunch break, resuming at 2:30 and continuing until dinner, with after-dinner jams that sometimes went as late as 11 or 12.

I’m sitting now in a café/restaurant run by an American from Baltimore named Stephen, who opened the place a couple of years ago with his Shanghainese wife. It’s Tuesday, July 8, and this is the first day off we’ve taken since arriving on June 21st. We’ve rehearsed every afternoon and many an evening, sometimes putting in 10 hours or more in a single day. Li Meng, our keyboardist, is like me an early riser by habit, so we often work on new material or go over tricky parts at low volume before everyone else is up. We usually head into town, hailing the bright yellow electric golf carts that are the town's primary form of motorized transport, and eat at one of a number of spots that have come highly recommended: Bai Wei Xuan 白味轩, where they serve Yunnan standards like porcini mushrooms, braised beef with mint, and a fried farmer’s cheese of which I’m particularly fond; Xiang 12, with its quiet, lovely courtyard and solid burgers.

The sheer pleasure of focusing on music all day is immense. I’ve already decided that I’ll do this for a month every year, especially since our productivity has been, I must say in all humility, quite impressive. In 15 days, we’ve put the polish on nine songs, except for bass and drums; another two songs need lyrics but are otherwise basically done. They are, in no particular order,

此心安处是吾乡 (Ci xin an chu shi wu xiang — “Where the Heart Finds Peace, There Is My Home”), a mostly acoustic piece in waltz time, with lyrics drawn directly from the poem by the same name by the Song dynasty poet Su Dongpo (Su Shi). The song was written by Yang Meng and Li Meng, with the first half mainly Yang Meng, with quite clever acoustic guitar parts and a dramatic second half dominated by a strong melody line, done mainly with harmonizing electric guitars and featuring a key change I’ve always really liked.

时间里 (Shijianli — “In Time”), a spare, very melodic, somewhat melancholic all-acoustic piece for three guitars and piano written entirely by Yang Meng, with an odd tuning (our G strings are tuned up to G#). For listeners who liked 山海间 on our last album, this one will hit hard.

空间里 (Kongjianli — “In Space”), another Yang Meng composition, a somewhat pop-inflected mid-tempo rock song with a relatively simple structure for a Chunqiu song;

时空里 (Shikongli — “In Spacetime”), the third in this triptych of songs, this one mainly written by me with lyrics by Yang Meng. This one is all acoustic and piano as well, alternating between a 6/8 and 4/4 time signature, and featuring a long acoustic guitar solo at the end as well as some tricky playing. There’s a marvelous piano solo over a cool rhythm part in the middle of the song.

短歌行 (Duangexing — “Short Song Ballad” as the original poem has been translated) is based on a poem intoned before the great Battle of the Red Cliffs by the warlord Cao Cao. Yang Meng and I co-wrote the music to this one. The instrumental motifs are my main contributions, and the chords and melody of the sung parts are Yang Meng’s.

黄金一代 (Huangjin yi dai — “The Golden Age”), a gorgeous all-acoustic ballad that Yang Meng wrote years ago and that we used to perform as part of our acoustic set. This one is just plain pretty, with a strongly melancholic feel that is somehow nevertheless uplifting. Lyrically, it namechecks many titles of songs from our first album back in 2006.

行者无疆 (Xingzhe wujiang — “Traveler Without Boundaries”) — A very Taoist-inspired song that features strongly pentatonic melodies, with quite a wide dynamic range from spare sections that use a lot of space to a dense motif based on a melody stretching across 16 measures, all done in three-part harmony.

无主之地 (Wu zhu zhi di — “The Masterless Land”) is a down-tempo, almost Doom Metal-like song I wrote the music for that uses tritones extensively, and has a kind of post-apocalyptic lyrical theme, its melodies done in a kind of call-and-response with lots of vocal harmonies.

冷兵器的诱惑 (Lengbingqi de youhuo — “The Seduction of Cold Steel,” still a temporary title) is a fast 6/8 riff-based rocker of my devising, with some musically challenging passages and anthemic parts.

侠客行 (侠客行,”The Hero’s Journey”) is our adaptation of an excellent poem by Li Bai, of the Tang dynasty. This one blends Central Asian and Chinese (pentatonic) themes and melodies, using a very cool delay effect to give the arpeggiated chord outlines a complexity and depth that we all really liked. This one is mainly Yang Meng’s composition but I did the arrangement. This one came together very quickly: Yang Meng played and sang it with simple chords one evening after dinner, and the muse of arrangement suddenly alighted and I insisted we rush up to my room and come to experiment with some ideas that, I’m pleased to say, worked rather perfectly.

起源之路 (Qiyuan zhi lu — “The Path of Becoming”) — Largely my composition along with Li Meng contributing mightily on arrangement, this one isn’t yet complete. It’s an unapologetically progressive rock or progressive metal song, about eight minutes in length, and both lyrically and musically it’s a bildungsroman of sorts, tracing the path from childhood through adolescence to adulthood and old age. It features a lot of odd time, some whole-tone scale sections, and is quite musically challenging.

I’m sure other bands have different approaches to composition but ours has always been pretty much the same — something I’ll get into in the next installment. I’ll stop here for now! More when I’m back in Beijing, including a dramatis personae and a quick history of the band, the long-awaited arrival of Song Yang, whose bass really added so much to the songs we’d been working on, a visit to Shaxi from Adam Tooze, and our debut of new material.

Thanks for taking me back to Shaxi, I only went once in 2009 but just loved it, and the little villages surrounding it, which you described perfectly.

I really enjoyed reading this, Kaiser!