This Week in China’s History: Britain is first Western government to recognize the Peoples Republic of China

January 6, 1950

Listen to the audio narration of this column in the embedded player above!

To: Mr. Chou En-lai, The Minister for Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China

I have the honour to inform your Excellency that his Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, having completed their study of the situation resulting from the formation of the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, and observing that it is now in effective control of by far the greater part of the territory of China, have this day recognized that Government as the de jure Government of China.

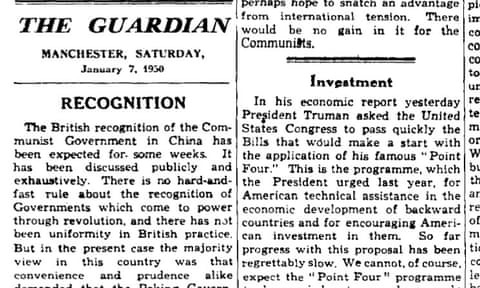

With this memo, the United Kingdom became the first Western government to recognize the Communist-led People’s Republic of China.

Mao had proclaimed the new nation on October 1, 1949, and in the month that followed, nine communist states — starting with the Soviet Union on October 2 — had recognized the People’s Republic. But as 1949 drew to a close, a complex, multi-sided process swirled around western decisions about recognition. Centered on Beijing, the decisions took into account not only the circumstances on the Chinese mainland, but also the British positions in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Malaya, the rump state of the Republic of China on Taiwan, the French colonial holdings in Indochina, and other geopolitical factors. As the Cold War emerged, Britain’s decision about whether to recognize Mao’s government became a microcosm for what lay ahead.

(As an aside, for an engaging view of the Cold War in Southeast Asia, through a British lens, read John LeCarré’s The Honourable Schoolboy, which made it onto Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf for the China Project.)

Surprisingly, perhaps, Great Britain moved quickly toward recognition of Mao’s government. In the first days after October 1, British diplomats had been lukewarm toward the Communists, matching the attitude of other Western nations, as the Soviet Union and its allies quickly established diplomatic ties. But even as the familiar Cold War lines seemed to be forming, Britain was considering a different path. By late October, the official position was changing. Writing in The Journal of International History, historian David C. Wolf describes that British Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin was advising early recognition. Bevin was unconcerned that Britain's allies were hesitant about this strategy, arguing that Britain’s “greater interest in China than other nations” gave it a unique role to play, and, besides, “Nationalist resistance is nearly hopeless and control by the Nationalists over Chinese territory on the mainland is negligible.”

By raising the question of the Chinese Nationalists, the British position takes on by implication the question of Taiwan. It is easy, in hindsight from the 21st century, to see that the autonomy and viability of Taiwan was a crucial factor in any country’s decision about PRC recognition, but at the time the issue was not so plain. Wolf describes the British as “surprisingly noncommittal on the future of Taiwan,” and giving little consideration to the chance of a “two-state” solution. With the Communists plainly in control of the country, the British approach appeared to be one of recognizing facts on the ground. Britain was also not sold on the idea that Taiwan — which had been annexed by Japan in 1895 — could be considered Chinese territory and thus the site of a legitimate Chinese government.

American interests in Congress were certainly keen to maintain support for the KMT, and this was a vital component of America’s hesitation about recognition, but the issue was not as stark as it would later become. U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson urged the British to delay their recognition, stating that the U.S. would continue to support the KMT. Other Western powers aligned behind the American position: some (like France and the Netherlands) because of concerns over the disposition of their colonial holdings. Others (including Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) were more concerned about jeopardizing their relations with the United States.

Ultimately, the greatest concern for British officials was the fate of Hong Kong. The CCP had consistently assured British interests that a Communist China would not take Hong Kong by force, but the colony’s leaders were unconvinced, influenced in part by the experience of 1941 when the territory had fallen to Japanese invaders. British leaders — and to some extent the British public — felt that recognizing the PRC would facilitate better relations between China and the UK, assuring Hong Kong’s future. At a time when Britain’s empire and influence abroad were both shrinking, Hong Kong represented the best chance to demonstrate Britain’s value. This was especially true as European empires in Asia collapsed, emphasizing Hong Kong’s value and uniqueness.

There was another angle as well: if Britain’s actions could improve its relations with the PRC, it might pull China away from the Soviet Union. On this issue, the United States and Britain differed: the U.S. was convinced that trying to divide communists from one another was futile, while Britain, in the words of Foreign Minister Bevin, argued that “the Chinese Communists were first and foremost Chinese and that they were not capable of becoming Russians overnight.”

The British government retained misgivings about the Communist government but, as Winston Churchill put it in the address that Wolf borrowed for his article’s title, “The reason for having diplomatic relations is not to confer a compliment, but to secure a convenience”: Britain needed relations with the “large part of the world's surface and population under the control of the Chinese Communists.” It was decided in mid-December that recognition would be conferred on January 6, 1950.

The United Kingdom’s actions appeared to set a trend. Ceylon and Norway recognized the PRC on the same day as Britain’s announcement. Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Switzerland, Israel and Afghanistan conferred recognition later in January. Even the United States, though it took no action, signaled a change in policy when Harry Truman convened a press conference on the eve of Britain's recognition to say that “The United States has no desire to obtain special rights or privileges, or to establish military bases on [Taiwan] at this time. Nor does it have any intention of utilizing its Armed Forces to interfere in the present situation. The United States Government will not pursue a course which will lead to involvement in the civil conflict in China [and] will not provide military aid or advice to Chinese forces on [Taiwan].”

Optimism about Western relations with the People’s Republic soon foundered for numerous reasons. The British move to recognize the PRC was based on the expectation that diplomatic relations would be quickly established. The Chinese government dashed this hope, requiring that disputes over property, representation in the United Nations, and the status of Hong Kong and Taiwan be resolved before diplomats could be exchanged.

Whatever momentum there was was stopped dead later in 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea. Taiwan changed from being a vestige of one war to being on the front lines of another. American support of Taiwan — and Hong Kong — became a pillar of its foreign policy. With the exception of France (1964) it would be more than 20 years before another Western country recognized the People’s Republic.

Counterfactuals are fraught exercises, but there is little reason to think that either China — and especially the Chinese people — or the West benefited from the decades when much of the international community pretended that the People’s Republic simply did not exist. Isolation and exile breeds mistrust and fear, and both multiplied during those years. Let us hope that we can avoid falling into similar traps in the years ahead.

Yes, that’s a fair observation. Good point

I don't think Guangzhou was the last mainland city to be "liberated," on Oct 14. The PLA did not enter Chengdu until Christmas Eve, shortly after Hu Tsung-nan fled to Taiwan. See Skinner's Rural China on the Eve of Revolution (full disclosure: I edited that book). Interesting that Skinner, having learned really fluent spoken Chinese in Sichuan, spells the general's name Fu Tsung-lan.