Listen to Kaiser’s narration of the column in the embedded player above!

I’ve been doing this column — with a brief hiatus — for about three years, exploring aspects of China’s history from the third century to the 21st. I’ve construed “China’s history” very broadly, including adventures of Chinese abroad, and of foreigners in China, and overseas Chinese communities.

One element of China’s history that I have tried consistently to emphasize is its global context. Rarely do events in one country (however that country is defined) occur without influence from or on others. And that applies to authors as well as subjects. So, writing in the United States on the eve of a presidential election that has been unprecedented in many ways, I thought it appropriate to turn to an event that touches on the histories of both China and the United States, and specifically one that fed into a presidential election with historical policy implications amid rising anti-immigration sentiments and charges of voter fraud.

In the fall of 1880, Denver, Colorado, was seething in anticipation of the election between Republican James Garfield and Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock. Chinese immigration was the hot issue in America’s Western states, with Democrats advocating more anti-immigrant and racist policies. This was the case in Colorado, where the staunchly Democratic Rocky Mountain News was provocatively xenophobic, “fervently advocating violence against the Chinese in its inflammatory racial rhetoric,” according to historian Jingyi Song in her 2020 book Denver’s Chinatown. Song continued. “In its daily exposés, the News constantly depicted the Chinese as a social menace to the white American community with its opium drug business and its alleged temptation to prey on innocent white women.” A campaign poster of the time depicted Garfield hugging a Chinese girl, with the headline “Garfield may become a Mandarin, but a President, never.” One shop window in Denver depicted Garfield, and the cabinet he would appoint were he to be elected — all Chinese.

With election day just three days away, anti-immigrant forces in Denver staged a torchlight parade — the largest of many such demonstrations that fall — on the evening of October 30th. Historian William Wei (now the State Historian of Colorado) described the scene in his book Asians in Colorado: after “the biggest parade Denver had ever seen… an estimated three to four thousand torch-bearing marchers assembled to hear speeches” in the city's center. Eight speeches were given that night; seven of them, according to Wei, were anti-Chinese, warning that if elected, Garfield planned to import Chinese laborers. “In the midst of the Sinophobic speeches,” Wei writes, “loud and prolonged cheering when [the Secretary of the State Democratic Party Committee] informed the crowd that the demonstration was already having the desired effect” and that Chinese were going to the telegraph office to tell their families not to come to Colorado, and that they they were planning to leave Denver.

The next day — October 31 — tensions remained high, exacerbated by the xenophobic rhetoric of the night before. Around 2 p.m., three men — two Chinese and one white — were playing pool at a saloon. Two white railroad workers, apparently drunk, entered the saloon, “John’s Place,” and began harassing the Chinese. Although some reports allege that violence began in response to the Chinese either drawing a knife or firing a pistol, the saloonkeeper’s testimony states differently. As recorded in Wei’s book, the saloonkeeper, John Asmussén, “advised the Chinamen to go out of the house to prevent a row, and they went out at the back door. After a few minutes, one of the white men went out at the back door and struck one of the Chinamen without provocation. Another one of the gang called to one of the gang inside to ‘come on Charley, he has got him,’ and he picked up a piece of board and struck at the Chinese…. This was the beginning of the riot.”

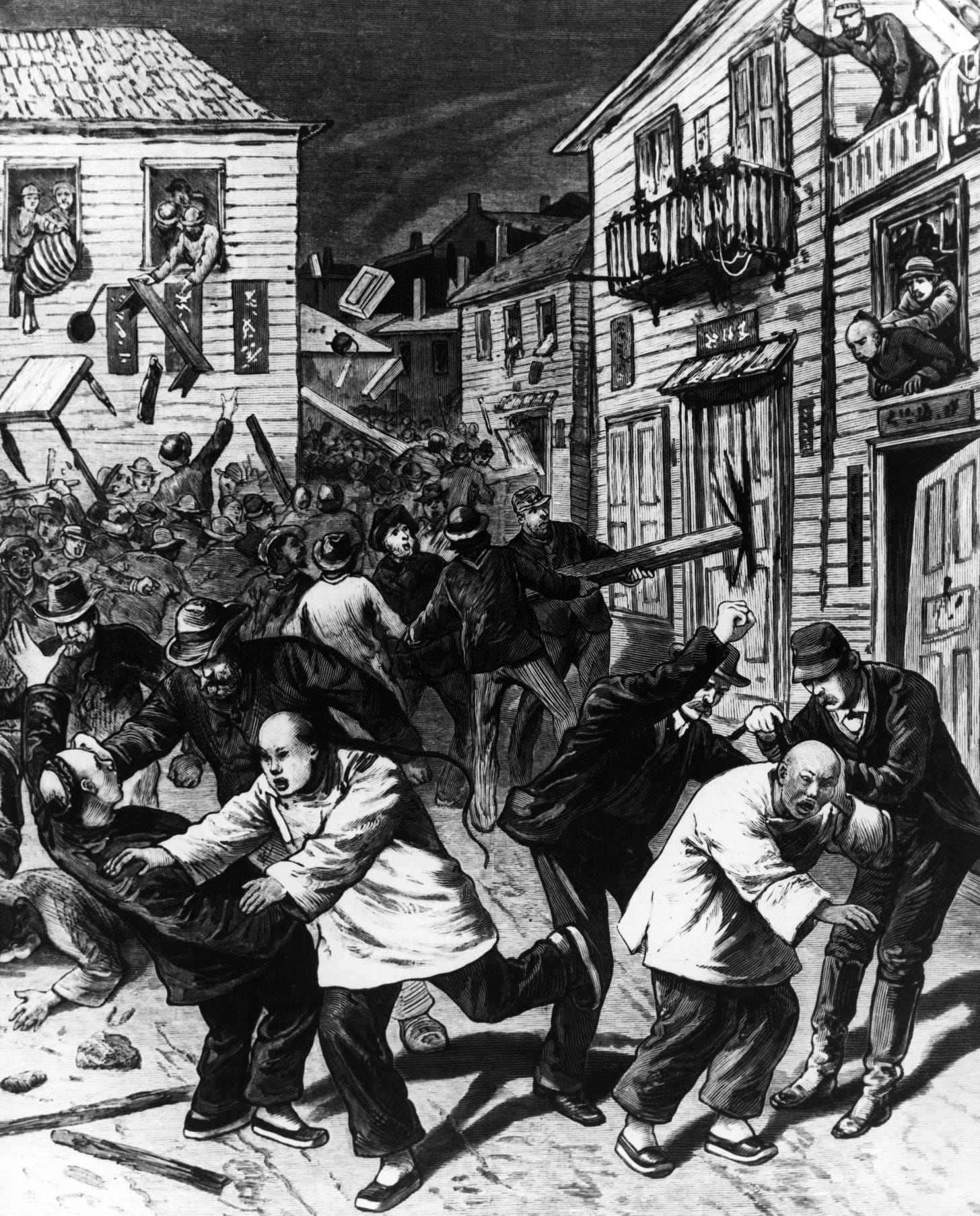

From this beginning, Denver collapsed into violence. Between three and five thousand people (remember that Denver’s population was just 40,000) rampaged through Denver all afternoon and into the night. As the mob grew in size, fewer than a dozen police officers were on duty, and the mayor’s attempts to calm the rioters had little effect. The mayor tried to disperse the crowd by directing the fire department to spray them with hoses, but this served only to antagonize them.

Notably, the police did not use deadly force, a fact many (including Chinese consular officials) found out of character given Colorado’s firearms culture. Just a few months earlier, the governor had ordered military intervention to put down a miners’ strike in Leadville, but he declined to do so in this case, citing the proximity to the election, and officials restricted themselves to hoses and stern warnings. To protect the Chinese population, police took several hundred into custody, imprisoning them in jail for their own protection.

Not all were protected. Dozens of Chinese were pulled from their homes or businesses and beaten, tortured, and lynched. Look Young, who had come from Canton about six months earlier, was taken by the mob and gruesomely attacked. As Wei describes, “After cutting off his queue, perhaps for a trophy, the mob proceeded to torture him before hanging him from a lamppost. They then forced him to run a short distance, catching him and beating him severely, and then forced him to run again, catching him and beating him once more. Finally, he was pushed to his knees and held there while one person kicked him and another hit him repeatedly in the head.” Two doctors managed to get Look away from his attackers, but were unable to revive him and he died shortly afterward.

Improbably, Look Young was the only person killed that afternoon. Dozens more were injured, many seriously. Denver’s Chinatown was devastated by the violence, and the homes of most of its residents — left unguarded while the occupants were held in protective custody in the downtown jail — had been ransacked and looted. Looking approvingly at the destruction, the Rocky Mountain News celebrated that “Washee washee is all cleaned out in Denver.”

The next day, both political parties tried to capitalize on what had happened. A counterprotest was held, also by torchlight, that gathered nearly 3,000 people who were ”indignant with the riot, and took the occasion to rebuke the mob.” Meanwhile, in nearby Leadville, several hundred Democrats gathered to celebrate the riot, while an even larger number of Republicans marched denouncing it — though to be clear, the Republican position opposed the violence of the riot but not the sentiment behind it. As Wei describes the sentiments of one Republican, he “did not desire to see the Chinese in this country any more than the anti-Chinese did, but he was in favor of humanity. If the Chinese were obnoxious, they should be removed in some other way.”

The election of 1880 was held, and Garfield carried Colorado and its three electoral votes on the way to winning the presidency. Chillingly, he served only six months before being assassinated.

For the victims of Denver’s Chinatown riot, there would be no justice. The Denver City Council denied any responsibility for the riots and rejected all claims for reparations or compensation. Three suspects were arrested and tried for the murder of Look Young, identified by several witnesses, including the doctors who had attended to Look Young and one of Look’s friends who had narrowly avoided the same fate. Nevertheless, a jury accepted the alibi from friends and coworkers and acquitted the defendants. A handful of rioters were convicted of “disturbing the peace” and sentenced to up to a year in jail.

The Qing government sent its consul, Frederick Bee, to investigate the riot and its handling and concluded his inquiry convinced that the United States federal government would make good on the claims of the Chinese residents of Denver based on the treaty relationship that existed between the two states. He failed, however, to understand the political climate in the United States at the time. Rather than compensating victims, Congress instead moved quickly to make their presence illegal and hold them responsible for the violence they endured. On May 6, 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed into law, its preamble stating, in part, that “Chinese laborers [in] this country endanger the good order of certain localities within the territory.”

Much has changed since 1880, of course. Republicans, rather than Democrats, have anti-immigrant sentiment at the center of their platform, for one thing. Yet, demonization of migrant labor as an economic and moral threat pervades this campaign as it did in 1880, and violence, or the promise of violence, accompanies the rhetoric. And China, though in a much different state than it was as the Qing entered its final years, is one of the few issues on which there is bipartisan consensus: neither Democrats nor Republicans waste opportunities to blame China for all manner of ills facing America.

Is it too much to hope that we might learn from the past and steer a course away from the violence and xenophobia of the 1880s? If you are an American, your chance to make your voice heard is on Tuesday, November 5.

Researching this week's column was not encouraging: the similarities in the electoral rhetoric surrounding race and immigration in the 1880s was distressingly similar to what I have seen in the 2020s, including right now.