“This Week in China’s History” is free this week, but please support this newsletter by becoming a paid subscriber!

Listen to Kaiser’s narration of “This Week in China’s History” in the embedded player above.

Dawn comes late in Beijing in November. At 6 am, the sun has yet to rise, and so it was still completely dark in the Rényín 壬寅 year, 1542, as the Jiājìng 嘉靖 emperor slept in the chambers of his most favored consort, Lady Cao — Cáo Duān Fēi. 曹端妃. He awoke abruptly, startled, then terrified, as he gasped for breath but found himself unable to draw air into his lungs. The sky was starting to brighten, but the emperor’s consciousness was fading. He was dying.

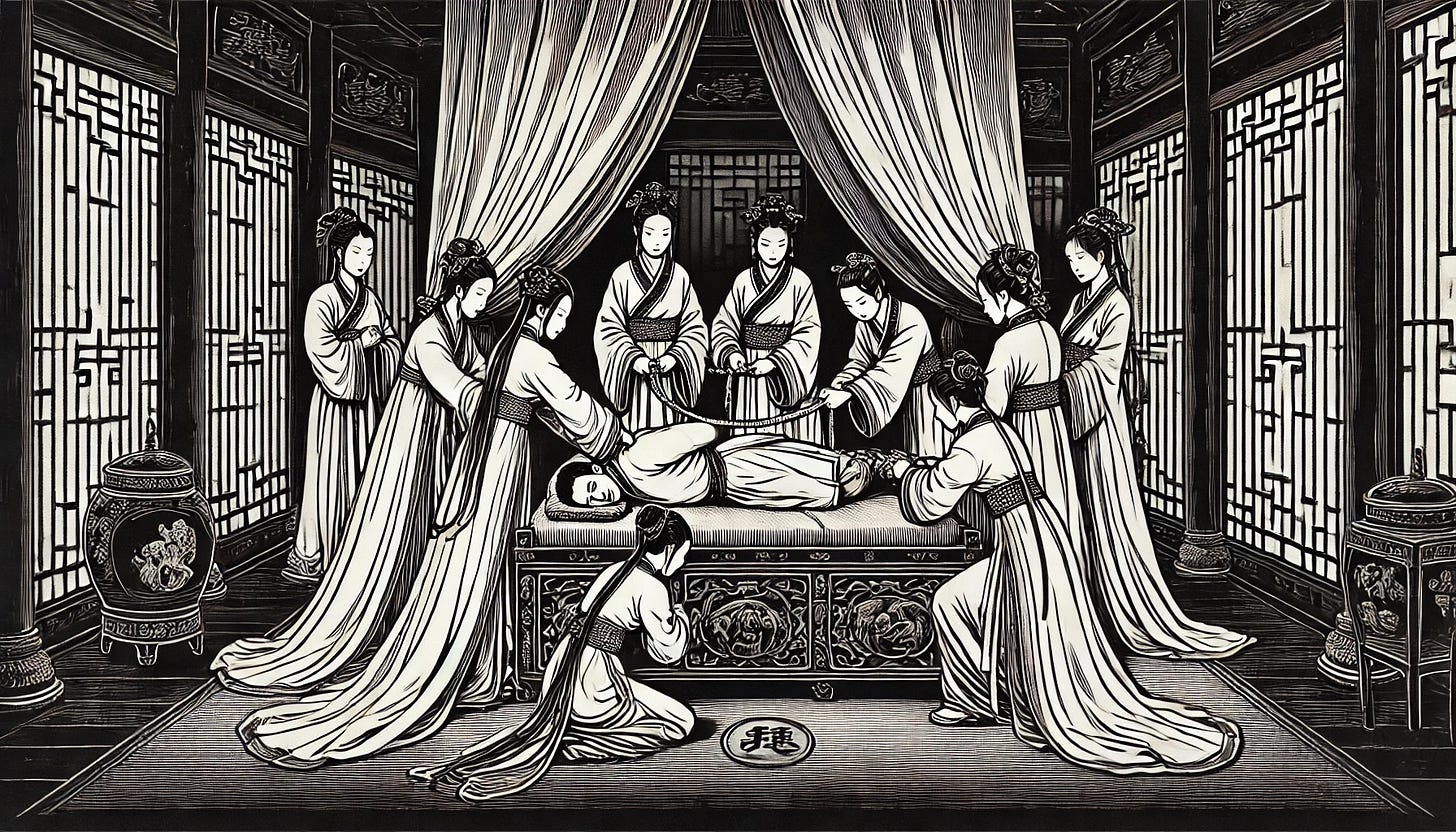

Surrounding the stricken monarch were nine women, palace women who were all consorts of the man who lay on the bed just like the ones they all shared with him. As life ebbed from the Jiajing emperor’s body, they did not try to aid him. Instead, they all helped subdue the struggling emperor. It was they who had wrapped a silk cord around his throat, tightening it so that he could not breathe and stuffing his mouth with another silk cloth. At least two of the women sat atop the emperor, keeping him from flailing or escaping. As he lost consciousness, it appeared that they had achieved their goal of murdering the head of the Ming dynasty.

What had driven these women not only to conspire to murder their sovereign but to go so far as to implement their plot to the point of apparent success? The answers lie in practices that demonstrate the concentration of power in the hands of both monarchy and patriarchy, leaving young women vulnerable and exploited.

Irregularity had accompanied the Jiajing emperor from the start. Born Zhū Hòucōng 朱厚熜, he was also known by the posthumous temple name 世宗Shìzōng, and the irregularity began with his ascension in 1521. He was not the son of his predecessor but his nephew, and rather than being posthumously adopted by the previous emperor (as was customary), he had instead had his father elevated (again, posthumously) to be emperor. This challenge to propriety and succession norms provoked the Great Rites Controversy, and some 250 scholars protested outside the imperial palace. The emperor responded violently: 17 protesters died after being beaten by palace guards. Others were exiled. The palace was purged of dissent, and the emperor’s succession was legitimated.

But questions about succession would continue to plague Zhu Houcong. After a decade on the throne, he had fathered no sons. Panicked that a succession controversy would be his legacy, the Jiajing Emperor sought advice on how to produce a male heir. Consulting with Daoist priests, the emperor increased the number of consorts he slept with — a logical enough response — but the advice did not end there. The emperor was prescribed a variety of elixirs, including “red lead,” a euphemism for a girl’s first menstruation. This was believed to contain concentrated yang essence that would also encourage the conception of boys. To make sure that this fluid could be collected immediately and to ensure the purity of the menstrual fluid, women and girls were sequestered far from public view and fed, according to some sources, a carefully regulated diet of mulberry leaves, like so many silkworms.

In 1533, the emperor finally fathered a son — three within a span of six months — but this did not end the torment of palace women. The Jiajing emperor was not only seeking male heirs but also pursuing the common Daoist goal of immortality — another way to avoid a succession controversy, I suppose. Immediately after their first menstruation, virgins were claimed to have a concentration of yang essence, which the emperor could absorb if he refrained from ejaculating during intercourse. For this purpose, more and more young girls were taken by the court. James Geiss, writing in the Cambridge History of China, records that nearly 1000 girls and women were taken, some of them as young as 10 years old.

The result of these tactics was that a large cohort of young women and girls were held, isolated, in the palace, their movements, diets, and bodies carefully monitored and controlled. Many of them were serially raped by the most powerful man in China. Other, more mundane, indignities included forcing these same girls to collect dew from the leaves of banana trees in the imperial garden in the pre-dawn.

If this weren’t enough, the methods that the emperor was using to enhance his virility were undermining his mental health. In his book Celestial Women, historian Keith McMahon writes that the emperor “experienced sudden fits of rage and madness.” The palace women came “to fear and hate him.” And in 1542 — 22 years after Zhu Houcong took the throne — they would have their revenge.

As McMahon describes it, the emperor went to bed that night in the chambers of Lady Cao, the mother of his first child (a daughter). While Cao and Jiajing slept, sometime before dawn, nine palace women came into the room and began strangling the emperor by tying a silk cord around his neck and stuffing another one into his mouth. Holding him down, they used hairpins to stab him, jabbing at his penis. The emperor lost consciousness, and it seemed that the plot would succeed.

But then things unraveled. To some degree, this was literal: apparently, the knot around the emperor’s neck was (depending on sources) not tight enough, or not correctly tied, allowing the monarch some oxygen. And then, perhaps seeing that the emperor might survive after all, one of the conspirators, Zhang Jinlian 张金链, got cold feet and alerted Empress Fang, the third and final empress of the Jiajing reign. Empress Fang untied the emperor (who regained consciousness but was unable to speak) and summoned palace eunuchs, who quickly moved in and took custody of the assailants.

Sixteen women were executed for the plot on the emperor, among them Lady Cao, who was apparently unaware of the plot that was carried out in her sleeping quarters. The executions — using the gruesome method of slow slicing, which kept the victim alive and suffering as long as possible — were carried out while the emperor was still incapacitated.

McMahon writes that “a dark fog hung about the place of execution for days, which people interpreted as the sign of the injustice of the sentence.” The emperor, fearing for his safety, moved his quarters to another part of the palace and never again left Empress Fang, who had rescued the emperor and had ordered the execution of the conspirators. She met her own demise five years later when a fire broke out in her quarters. The emperor declined to have the fire extinguished so she could be saved.

What is the lesson of the Renyin plot? Believing firmly that history is produced at the intersection of past and present, it is impossible not to see the ways that state power seeks to control women’s bodies and reproductive health. Certainly, women's autonomy in the Ming differed from what it is today. But in China, as elsewhere, we find the state wielding power over women’s bodies with regard to neither their wishes nor their wellbeing.

Image: OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com