“I went with my companions to the 湘潭 Xiāngtán market,” recalled the 17th-century merchant Wang Hui, writing in his memoir. Wang was entering the city, just south of Changsha, in Hunan, to investigate reports that Qing troops had slaughtered the city’s inhabitants as part of the Manchus’ conquest. “I heard something about a massacre in Xiangtan, but I doubted it was true.”

Wang was writing in the winter of 1649, during what historian Lynn Struve called China’s “general crisis.” Social, climatic, fiscal, political, and epidemiological disasters all befell China in the 17th century, but “the one calamity that stands out most in Chinese cultural memory… and which exacerbated all the others was the conquest of China by a coalition of ‘barbarian’ peoples from the far northeast, led by the Manchus.”

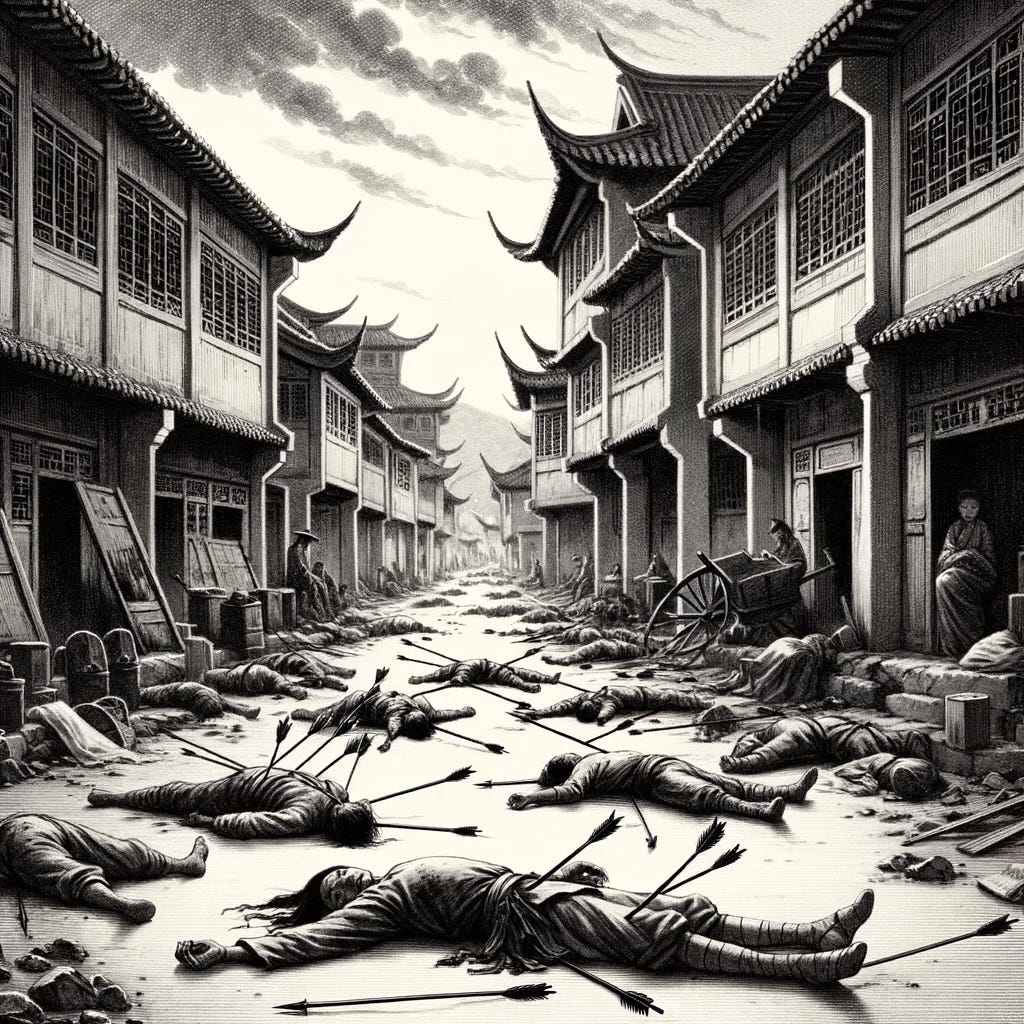

Wang Hui was about to experience that calamity firsthand as he walked into the market. “Our feet grew feeble as we walked forward,” he wrote. “Our souls left us, and our hearts chilled in fright. Traces of blood were still fresh and a rank odor was oppressive. One could hardly remain standing, nor could one swallow any food. There was only the sight of corpses and heads strewn everywhere, too ghastly to talk about.”

Wang was walking through the aftermath of one of many massacres that characterized the Qing conquest of the Yangtze Valley and central China. The slaughter in Yangzhou (1645) is perhaps the most horrific and best remembered. Even if the contemporary estimate that 800,000 people died is too large (historian Antonia Finnane suggests it may be 10 times too high), the city was devastated. By that measure, the sacking of Xiangtan deserves the same kind of attention. Accounts like Wang Hui’s suggest that only a few hundred people survived the slaughter.

In her classic book on that era, Voices from the Ming-Qing Cataclysm: China in Tigers’ Jaws, Struve contends that “most textbooks characterize the Ming-Qing transition as a relatively short and smooth one…a minor blip.” Yet, that conquest had begun five years earlier — and earlier still, if you consider the defeats inflicted by Manchus on Chinese armies in the decades leading up to their invasion of the Ming capital in 1644.

What happened — and why — in Xiangtan illustrates part of why the Qing conquest was far more than “a minor blip.” It was indeed the cataclysm of Struve’s title, in part because conquest is always brutal and traumatic, but also because reducing what happened to one dynasty succeeding another obscures a chaotic political scene that drove violence.

The Manchus had been fighting against the Ming since the start of the 17th century, with an eye toward supplanting them as rulers of China. The Manchus approached the Great Wall at 山海关 Shānhǎiguān in the spring of 1644 with this goal in mind, but when they reached the gates of Beijing, it wasn’t the Ming they toppled. The rebel 李自成 Lǐ Zìchéng had led his own army into Beijing a few weeks earlier, driving the last Ming emperor to suicide and then putting the Forbidden City to the torch when it became clear he would be unable to maintain power.

This allowed the Manchus the ability to claim they were avenging the Ming rather than displacing them, but the technicality was weak sauce for those who had served the Ming. A robust resistance arose, but it was itself divided among rival claimants to the throne. Besides the Ming loyalists of various stripes, the rebel movements that had brought down the Ming — and Li Zicheng was not the only one — remained at large. And, of course, the Manchus were a foreign occupying army, culturally and linguistically distinct from the people they were seeking to rule. Throw unfamiliar geography and climate into the mix, and it’s not surprising that the Qing found their conquest slow going.

Several years after the Battle of Shanhaiguan and the taking of Beijing, the conquest was far from complete. The remnants of the Ming court — the Southern Ming — even mounted a counteroffensive. Frederic Wakeman, in his encyclopedic The Great Enterprise, notes that in the fall of 1648, most of southern China was in the hands of the Southern Ming, with “Qing authority confined to a few enclaves in Guangdong and southern Jiangxi.”

In response, “the Qing court sent two powerful military columns into the south… a mixed Mongol-Manchu-Han force of thirty thousand” led by three senior Qing generals. One of these, the Manchu prince Jirgalang, found his advance slowed by troops under the command of Li Zicheng’s nephew, Li Chixin. Li’s men — or at least their leaders — had declared loyalty to the Southern Ming, but far from regular soldiers, they were bandits at their core, having joined a peasant rebellion bent on overthrowing the Ming before transitioning to support it. Their occupation of Xiangtan was itself an ordeal for the city. Wang Hui describes them as an undisciplined “bandit horde” whose commanding officers “had been spending every day in a drunken stupor.”

Wang Hui described the arrival of the Qing soldiers in Xiangtan on the 28th of February, 1649 “a hundred horsemen came on a reconnaissance patrol… the bandit horde, without time to either put on their armor or saddle their horses, held up their arms to shield their heads and scurried away like mice.” Foreshadowing what was to come, the Qing soldiers pursued and killed them.

Aggravated by the difficulty of his march to Xiangtan, Jirgalang took out his frustrations on the city. He ordered “heavy punishment” in the form of six days of massacre, and “even after he commanded his soldiers to sheathe their weapons, they continued to slaughter for another three days.” The result was the macabre scene that Wang Hui walked into, two weeks after the killing had ended.

The descriptions of Xiangtan — the stench of death, bloodstains, corpses and body parts strewn across the city — are part of a body of evidence that shows the extent of the trauma inflicted on China by the Manchu conquest, and the whole thing wasn’t accomplished until, perhaps, the 1680s, four decades after Dorgon crossed the Great Wall at the head of a Manchu army. Why, then, do we so often see the Qing conquest as a short, neat process? Struve suggests several reasons, including sources that tend to come from elites, reluctance to fan nationalism by demonizing the Manchus, and a similar desire to promote empathy with the “bandits” who lacked privilege and resources.

In our own age, we see the trauma of war everywhere. It is worth recalling the “Ming-Qing Transition” — itself a clinical label that obscures the violence and terror that defined the age — to remember that war and conquest are chosen and led by governments and officials, but it is the common people who suffer the consequences.