TikTok, China, and the Crisis of American Confidence

Finding myself on the same side of an issue as Donald Trump is, as anyone who knows my politics can doubtless imagine, rather bewildering. Yet here we are: Trump opposes the “Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act,” and so do I.

There is, I daresay, no overlap between his reasons for opposing it and mine. Admittedly, like Trump, I nurture no small animus toward Meta, but in my case, it’s chiefly for having set in motion and stoked the fear of TikTok that now seems to grip DC: I don’t regard Meta as an “enemy of the people” as Trump does, and frankly was glad to see Facebook de-platform him after January 6. And unlike Trump, I can’t claim to have any megadonors of either party who happen also to be major shareholders of TikTok’s parent company ByteDance. I don’t, alas, have megadonors, period.

The bill would remove TikTok from all app stores in the U.S. and prevent its distribution unless Beijing-based ByteDance sells the company, presumably to an American or at least “Western” buyer. I oppose the bill for the same reasons I fear another Trump presidency: Because it would erode or even eviscerate core values that I hold to be the foundations of American strength, chief among them openness.

Somehow, its proponents don’t see this: the bill made its way unanimously out of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and now looks to be headed to the floor of Congress. Its fate in the Senate is uncertain, but the Biden White House has already signaled its support for it. Why a bill that strikes me, on its face, as so fundamentally un-American can garner this much support is baffling and worrying to me. Clearly, we aren’t thinking clearly.

We’re not thinking clearly because we’re in the throes of yet another full-blown moral panic. Let’s admit we have a bad track record as a nation when it comes to making decisions in that mind state: Prohibition, the War on Drugs, the Satanic Panic of the 80s, and the Patriot Act after 9/11 come to mind. Now, it’s China that has us on the verge of another episode of serious self-harm. I have little doubt that a decade from now, our present histrionics will cause us as much embarrassment and shame as the national freak-out over back-masking in records or Dungeons and Dragons does now.

Mike Gallagher’s Select Committee, which pronounced China an “existential threat” to the U.S. right out of the gate, has given a lot of oxygen to the current panic and deepened the national paranoia, but has otherwise done very little. Now, with Gallagher declining to stand for reelection and the Select Committee already in overtime — its mandate was to end on December 31, 2023 — it seems he’s determined to inflict one wound at least before he leaves the stage. The problem is the damage will be mostly to the U.S. and not, as he imagines, to China.

Killing TikTok unless it submits to expropriation — let’s call this what it is — would be more than just a policy shift: It would constitute a retreat from core principles and, ironically, the embrace of the Chinese concept of “internet sovereignty” — a concept we’ve rightly long opposed. But becoming more like China to meet ostensible challenges from China isn’t just a terrible idea because it represents a betrayal of our values. Worse, it won’t even work. It will have been for nothing. “In a race to the bottom, China will always win,” as a senior American diplomat once said, “because they can go lower.”

Whenever restrictions to TikTok come up in conversation, someone is bound to raise the issue of reciprocity. I get it: It seems grossly unfair. Facebook, X (née Twitter), Instagram, YouTube and the lot are all blocked in China. Why shouldn’t we do the same to TikTok? Leaving aside, for now, my more fundamental problem with this argument — that, as I’ve already suggested, blocking Chinese-owned social media because China blocks ours is a surrender of the moral high ground and weakens us by eroding our faith in openness — let me suggest that if we must have reciprocity, we already have on the table a highly reciprocal approach that ByteDance itself has put forward, devised in partnership with Oracle. It’s called Project Texas.

Project Texas, a $1.5 billion proposal advanced in response to CFIUS concerns over TikTok’s handling of data, would house all that data on Oracle servers in the eponymous state, with the whole data operation overseen by U.S. nationals. It would have made — and still could make — TikTok the most locked-down, carefully supervised social media property in the U.S. if not the world. And it resembles very much the agreement that Apple has in place, under China’s data localization requirements, to store its Chinese users’ iCloud data with Guizhou Cloud in Southwestern China — what I meant by reciprocity.

But Project Texas wasn’t enough to satisfy China hawks like Senator Marco Rubio, who in 2022 signaled his opposition to the deal and forced ByteDance to shelve that solution, at least temporarily. This is a shame: Project Texas still strikes me as a sensible compromise that would have addressed most data security concerns while allowing TikTok to continue to serve its 130 million or more users in the U.S.

The drive against TikTok is predicated on fears that it could use U.S. user data in ways that threaten national security. Theoretically, sure, there is that possibility. I wonder, though, why Beijing or its intelligence services would be keen squeeze ByteDance to get their hands on the type of data that TikTok generates when there are easy sources for acquiring far more valuable data that don’t involve leaning on (and thereby jeopardizing) a large, valuable, and highly profitable private Chinese company — indeed, the only Chinese social media property ever to have gained substantial traction internationally.

Preemption of this sort is not the norm in American jurisprudence, where ordinarily punishment is only given out for demonstrable intent to take malign action, or for actions taken — not for potential actions or a latent threat. So far, despite rumored claims of a "smoking gun" of nefarious use of data by TikTok, evidence remains conspicuously absent. Data may have been sent to China, counter to claims made by the company, and allegations of privacy violations or improper use of data by former employees have been reported. So far none of these implicate Beijing or rise to the level of a clear and present national security threat.

There are, and ought to be, national security exceptions to this that justify preemption. But the action taken in response must be one that actually addresses the concern — in this case, the danger that foreign governments and especially governments of adversaries could acquire data and put it to malign use. So long as data can be so easily harvested from a multitude of other sources (whether through purchase from data brokers, or through hacking as was the case with Saudi Arabia, whose agents successfully infiltrated Twitter and stole information related to Saudi dissidents in 2014-2015), it’s clear that the proposed bill does not represent a good-faith effort to remedy this threat: It only targets one app, representing a small fraction of the data that any bad actor could access, and protects data of a relatively non-sensitive nature to boot. Meaningfully regulating social media — all social media — feels politically impossible to too many of our legislators in this moment. And there’s an easy scapegoat to hand.

Proponents of the TikTok bill say that they’re worried about Chinese influence operations — that TikTok will be a powerful conduit for propaganda. Leaving aside, for now, my right as an American to see even the most rank propaganda if I really want to, one has to ask: Is this alleged Chinese influence actually working? If it were, would you not expect to see opinions of China in the U.S. improving? They clearly are not: They’ve worsened dramatically across the years, and never more precipitously than in the years when we’ve worried most about the supposed threat.

So let’s be honest at least about why we’re doing this: It’s an emotional reaction to do something in the face of this supposed threat from China. But it’s a move that will weaken, not strengthen us. The parallels to another misguided, emotionally driven policy are uncanny: our foolish decision, during the Trump presidency, to place major curbs on immigration from China and to target individuals with ties to China over fears of industrial espionage. Just when it became clear that we needed more scientific and technological talent in the U.S. to compete with China, we decided to limit the inflow from one of its richest sources and to make the U.S. a markedly less hospitable environment for Chinese talent. “For years China has struggled to stop the ‘brain drain’ from its overseas-educated citizens staying abroad,” wrote Jeremy Daum of the Yale China Law Center in a recent piece. “It would be painfully ironic for our own outsized security concerns to be what finally stops that flow of talent from which we benefited for so long.” We sacrificed that great American strength — our openness — on the altar of national security, and we’re about to do it again.

There will be those who argue that this very openness is a vulnerability. I’ll grant that yes, it can be, but we’ve remained an open society because the benefits openness brings far outweigh the costs. Today, many appear to be convinced that the vulnerabilities tip the scales, and that, to me, is evidence or indeed proof that America is suffering an acute crisis of confidence. The enthusiasm in DC for this measure to force a sale of TikTok — something that, as Graham Webster of DigiChina has argued, is unlikely to happen — was, I suppose, the inevitable next step in the American slide into techno-pessimism: We went in the space of under a decade from believing that some intrinsic property of social media made it the ultimate weapon to undermine authoritarianism — remember the Color Revolutions and the Arab Spring? — to believing that social media was, instead, a tool that autocrats could wield just as well as democratic activists. Now, we’ve convinced ourselves that the nefarious CCP will use it to undermine American democracy.

Apparently, they don’t have to lift a finger: The mere threat has us undermining democracy just fine on our own. Is our confidence so badly attenuated that we can’t even hold aloft the values at the very core of our national vitality? Do we really need to behave like the censorious regime in Beijing to compete with China?

It’s this erosion of confidence I find particularly worrisome. American confidence is indeed shaken; poll after poll shows declining faith in our political leaders and in the electoral system itself. We become, in this state, more prone to scapegoating, and more likely to act out of emotion rather than reason. Sure, American overconfidence and hubris have led to some awful policy decisions, too — including in policy toward China. But having now seen how we behave as a nation when our confidence flags, I’m starting to miss the hubris.

Last week I watched President Biden deliver the State of the Union address, listening attentively to his relatively brief section on China. Here’s what he said:

For years, all I’ve heard from my Republican friends and so many others is China’s on the rise and America is falling behind.

They’ve got it backward.

America is rising. We have the best economy in the world. Since I’ve come to office, our GDP is up. And our trade deficit with China is down to the lowest point in over a decade. We’re standing up against China’s unfair economic practices. And standing up for peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait. I’ve revitalized our partnerships and alliances in the Pacific. I’ve made sure that the most advanced American technologies can’t be used in China’s weapons. Frankly for all his tough talk on China, it never occurred to my predecessor to do that. We want competition with China, but not conflict. And we’re in a stronger position to win the competition for the 21st Century against China or anyone else for that matter.

My immediate reaction was relief. We’re better when we’re confident — and the same is true for China. Indeed, as Ryan Hass has argued in a recent paper, national confidence on the part of either the U.S. or China makes for a better, more stable relationship: confidence on the part of both is better still. However, “when both countries simultaneously feel pessimistic about their national condition, as is the case now,” he wrote, “the relationship is most prone to sharp downturns.”

Again, I’ve decried the overweening, “indispensable nation” American pride that can, and has, led this country to folly in its foreign policy. But if the choice is between crippling fear of a ten-foot-tall China and a bit of chest-thumping and swagger, God help me, I’ll take the latter.

___

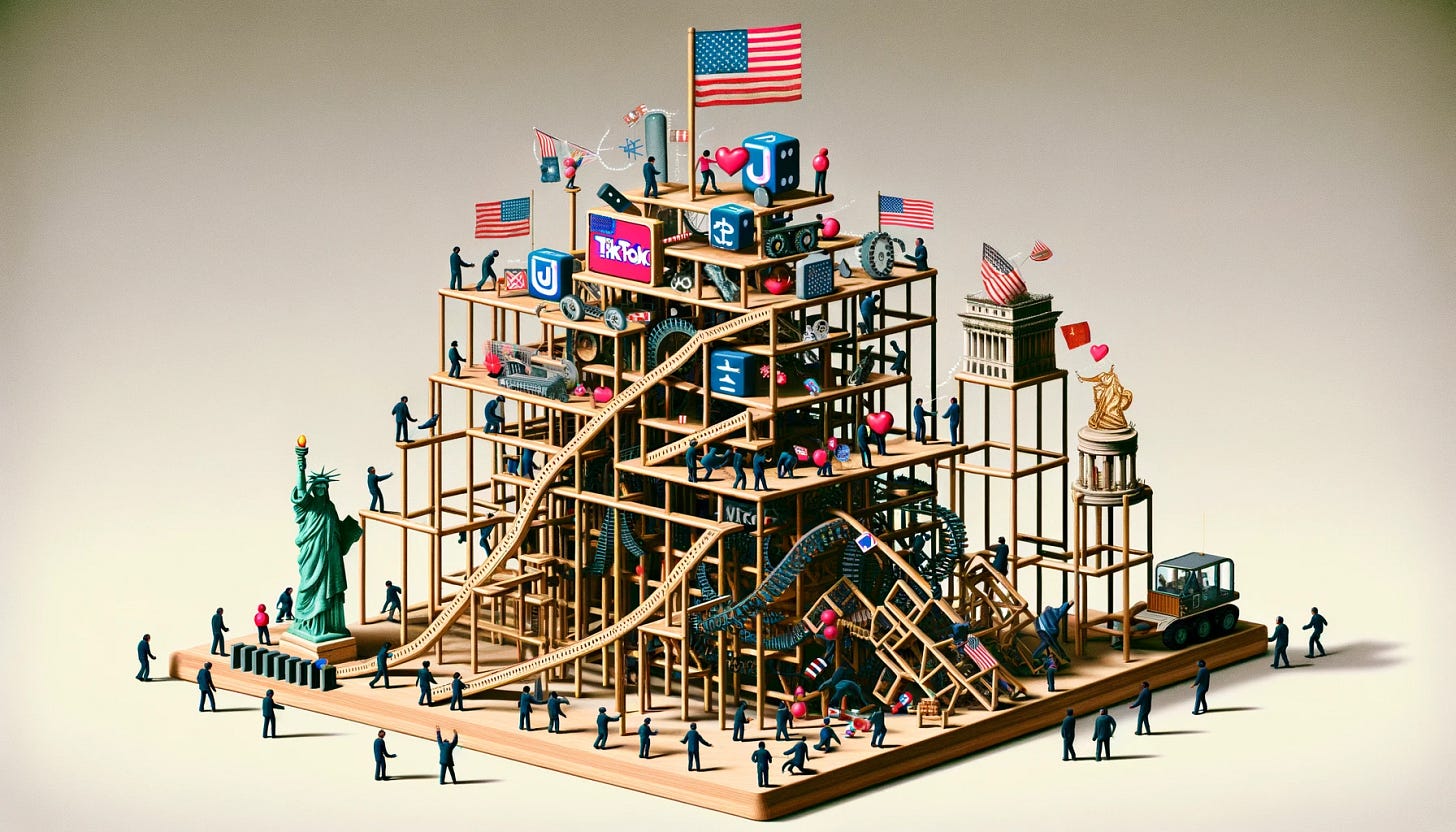

Image: OpenAI. (2024). ChatGPT [Large language model]. /g/g-pmuQfob8d-image-generator

One note. Project Texas was not just proposed. It has been mostly implemented, and those who dismiss it as an option do not seem to have made any effort to understand it. Which only shows clearly that the motivations are not about solving anything, just scoring political points.

I agree 100%. Thank You for a clear rendition of our current TicTok dilemma. If the program can bring down our government then Russia needs to be examined closely as well. What is Russia using? I have heard Facebook and Twitter currently masquerading as X . Let’s educate ourselves NOT knee jerk to some asinine fear counsel.