Trump Will Make China Great Again

China Perspectives by Sinology | Andy Rothman

Summary

Beijing’s economic policies need a reboot, and Donald J. Trump is here to help. The American president will provide Xi Jinping with the pressure and excuse to change his policies to make the Chinese economy great again.

China’s economy faces significant challenges but is far from collapse. Macro data for the first quarter of this year was, in fact, decent. Real (inflation-adjusted) household income and consumption spending both rose more than 5% year-over-year. China’s new energy vehicle sales were up 44% YoY during the first five months of 2025. These growth rates are high relative to most developed countries, but they are considerably slower than what China experienced a decade ago, so are disappointing to most Chinese.

The disappointing pace of growth has been due to several years of government policies which were well-intentioned but poorly thought out and chaotically implemented. Rather than fix socio-economic problems such as unequal access to housing and education, the policies damaged many small businesses, crashing entrepreneurial and consumer confidence.

Since last fall, Xi has been taking tentative steps to restore confidence and boost consumption. But, until Trump won the election, announced his historically-high tariffs and hired a team of China hawks with visions of kneecapping the world’s second-largest economy, it didn’t appear that Xi had the confidence to make the bold policy changes necessary to shift his economy into its next growth phase.

Xi must now recognize that regardless of how the current tariff chaos plays out, it is clear that Beijing must rely primarily on its own 1.4 billion customers — not foreign markets — to drive innovation and growth.

In the coming quarters, I expect Xi to accelerate and deepen his efforts to fix his own policy mistakes, with new programs to restore private sector and consumer confidence and encourage consumption.

Some foreign observers will be surprised by these moves because they believe Xi has developed an ideological aversion to the private sector and consumption. I don’t see evidence to support that view, and note that under Xi, private firms have continued to drive creation of jobs, innovation and wealth. The number of private firms increased more than four-fold since he became Party chief in 2012. Xi is clearly counting on the success of private firms, which account for 90% of China’s high-tech companies and which dominate the industries he is promoting: batteries, electric vehicles, and artificial intelligence.

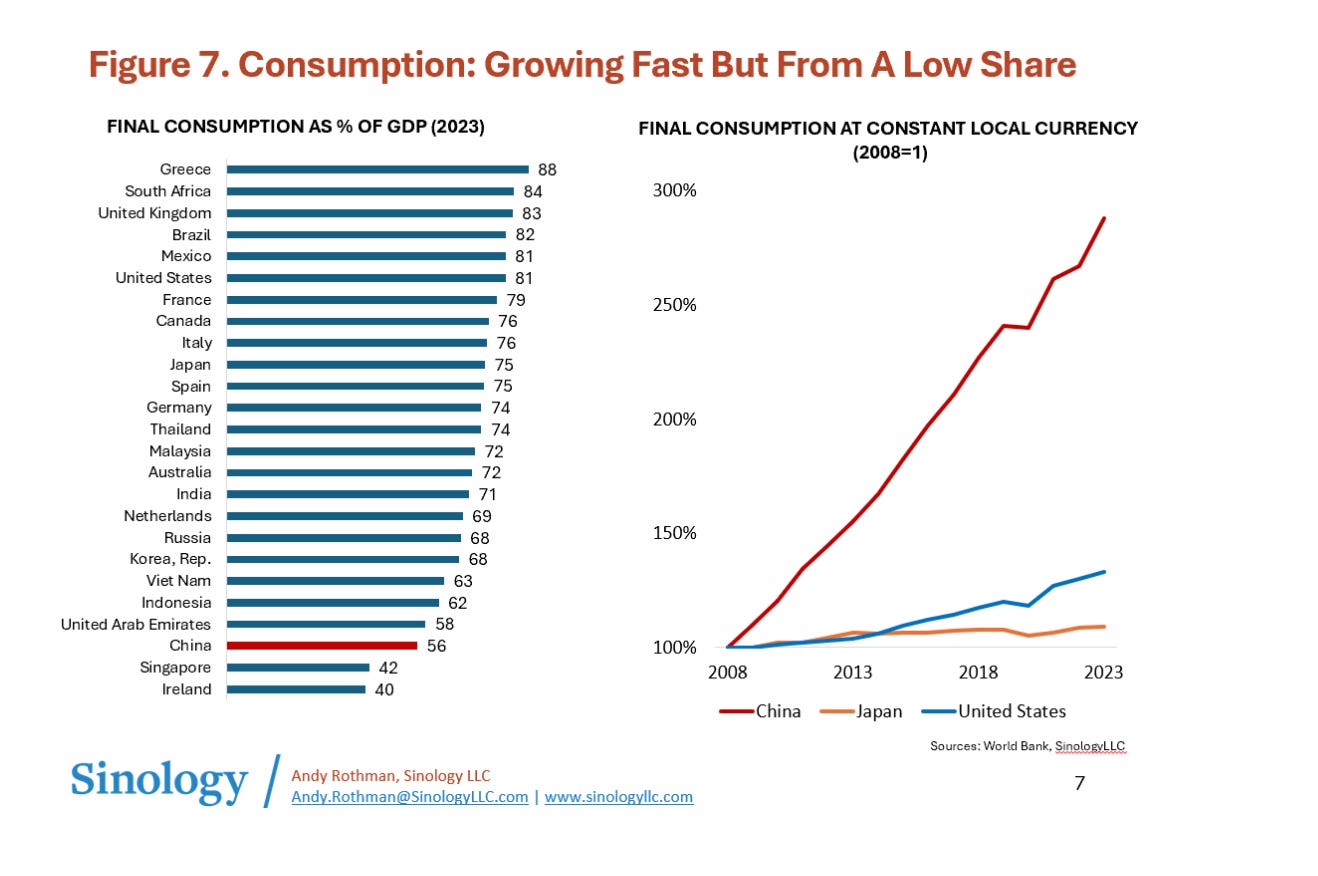

The policy changes will also surprise those who believe Xi is opposed to consumption as an economic engine. Final consumption already accounts for 56% of China’s GDP, and, in the five years before the pandemic, consumption contributed an average of 64% of annual GDP growth. Consumption in China has grown far faster than in the US for many years.

Trump also makes it easier for Xi to fix his recent policy mistakes: when Xi course corrects, he can say he is responding to Trump, rather than acknowledging his own errors.

While we wait for the policy changes, it is important for investors and corporate directors to avoid the headline distractions about China and pay more attention to the country that generates more global economic growth than the US and its G-7 partners combined.

DISTRACTION I – China Doesn’t Intend to Attack Taiwan

Don’t be distracted by headlines predicting imminent war across the Taiwan Strait. There is no evidence that Xi Jinping intends to use force to coerce unification between the mainland and Taiwan.

There is no domestic political pressure on Xi to use force. The vast majority of people in China are satisfied with the current situation, with most countries treating Taiwan as part of China, and with Taiwan enjoying informal, de facto independence, but not formal, de jure independence. The political key for Xi is to not be the leader who allows Taiwan to gain de jure independence, rather than to be the leader who uses force to achieve unification.

Using force would raise unacceptable military risks for Xi, as highlighted by the stalemate in Ukraine, where Putin only had to cross a land border. Attacking Taiwan would require a massive amphibious assault – one of the more complex military operations – over 100 miles of difficult sea and would risk drawing the U.S. into a catastrophic conflict. Preparations for a modern D-Day would be readily visible via satellite, and the US intelligence community is not reporting this. Xi could use missiles to destroy much of Taiwan, but this would be a hollow victory and lead to debilitating economic sanctions by many countries. A naval quarantine is also possible but would create unacceptable military risks of intervention by the U.S. Navy.

U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth stated in May that “Beijing is credibly preparing to potentially use military force to alter the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific. . . It’s public that Xi has ordered his military to be capable of invading Taiwan by 2027. . . The threat China poses is real. And it could be imminent. We hope not. But it certainly could be.” [emphasis added]

Hegseth’s remarks generated yet another wave of concern about the use of force by Beijing, but it is important to note that the Defense Secretary’s words were carefully hedged — “potentially . . .capable . . . could” — rather than declarative.

Other senior Trump administration officials have made clear that they do not believe the use of force by Beijing is imminent.

In March, the U.S. intelligence community published its Annual Threat Assessment, and did not forecast the use of force. The report, which is described as the intelligence community’s “official, coordinated evaluation,” stated simply that, “The PRC will continue trying to press Taiwan on unification.” The report was issued by the office of the Director of National Intelligence, run by Trump appointee Tulsi Gabbard.

In May, the senior American military commander in the Pacific, Admiral Samuel Paparo, addressed concerns — raised by Hegseth — about Xi ordering his military to be capable of using force against Taiwan by 2027. Paparo said this does not mean China intends to take action that year. “This is not a go-by date. It's a be-ready-by-date.”

Also in May, the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, in its Worldwide Threat Assessment, did not forecast the use of force by Beijing. DIA wrote that “China is likely to continue its campaign of diplomatic, information, military and economic pressure on Taiwan.” But, the report concluded that “China appears willing to defer seizing Taiwan by force as long as it calculates unification ultimately can be negotiated, the costs of forcing unification continue to outweigh the benefits, and its stated redlines have not been crossed by Taiwan or its partners and allies.”

The huge military risk of using force is matched by an equally daunting economic risk for Beijing. Starting a war across the Taiwan Strait would have devasting consequences for China’s economy.

Unlike Russia, China’s economy is globally integrated, and China depends on many strategic imports. Last year, over 70% of China’s oil and LNG consumption was imported. Over 80% of its iron ore and soybean (largely for animal feed) consumption was imported.

Even more importantly, last year, 72% of the semiconductors used in China (by value) were imported, with over one-third coming from Taiwan.

Starting a war with Taiwan would almost certainly lead to sanctions that would shut down most of these imports. And, even in the unlikely event that China were to capture TSMC’s semiconductor manufacturing facilities intact, operations would quickly cease as companies in countries like Japan, Korea, Holland, and the U.S. would halt shipments of critical materials such as process gases and other supplies and spare parts, as well as withdraw engineers responsible for the constant maintenance necessary to keep complex equipment at chip fabs running.

Many Taiwan companies appear confident of the future cross-Strait business environment. Last year, nearly 40,000 businessmen from Taiwan attended mainland conferences and trade fairs, according to a Taiwan-based research center.

Predictions of imminent war will remain in the headlines, but the probability of conflict is very low.

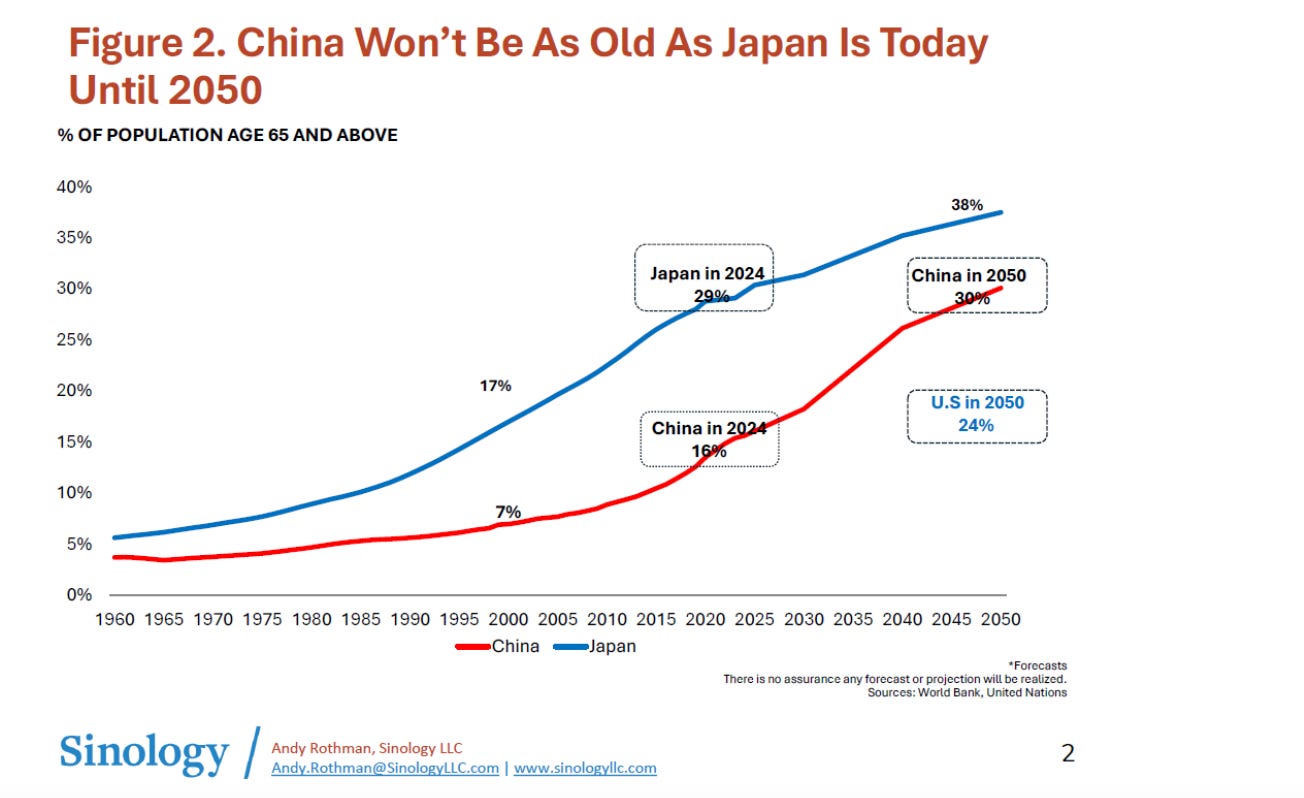

DISTRACTION II – Demographics

A second, frequent China distraction is demographics. While it is true that China’s population is aging, context is important. China won’t be as old as Japan is today until 2050. At that time, 30% of China’s population will be 65 or older, up from 16% in 2024. In 2050, 24% of the US population will be 65 or older. (Last year, 29% of Japan’s population was 65 or older.)

The Chinese government and Chinese companies are taking steps to mitigate the impact of the aging population. One measure is to invest in education, to prepare a smaller workforce for higher value-added jobs. Since Xi became head of the Party in 2012, central government spending on education has increased by 98%, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6%. The number of university graduates has increased by 75%, and government R&D spending has increased by 251%, with a CAGR of 11%.

The Nature Index is a global ranking that measures research output based on the number of articles published in high-quality research journals. When it was first released in 2014, only eight Chinese universities made it into the top 100. Today, that number has increased more than fivefold, with 43 Chinese institutions now ranking among the world’s best, surpassing the 36 American and 4 British universities in the list.

Chinese companies are responding to a shrinking workforce, and to rising wages, with a rapid increase in automation. China’s share of global industrial robot installation has risen from about 20% to more than half in only 10 years. And, in 2023, almost half of industrial robots installed in China were produced by domestic firms, according to the International Federation of Robotics.

China’s robot density ranked third globally at in 2023, at 470 units per 10,000 manufacturing employees, behind Korea (1,012) and Singapore (770), and well ahead of the US (295), according to the IFR.

Another step by the government has been gradually raising the statutory retirement age, which will slow the decline in the working age population.

China’s aging population is a long-term challenge, but the near-term risks are often exaggerated.

DISTRACTION III – Trump Tariffs

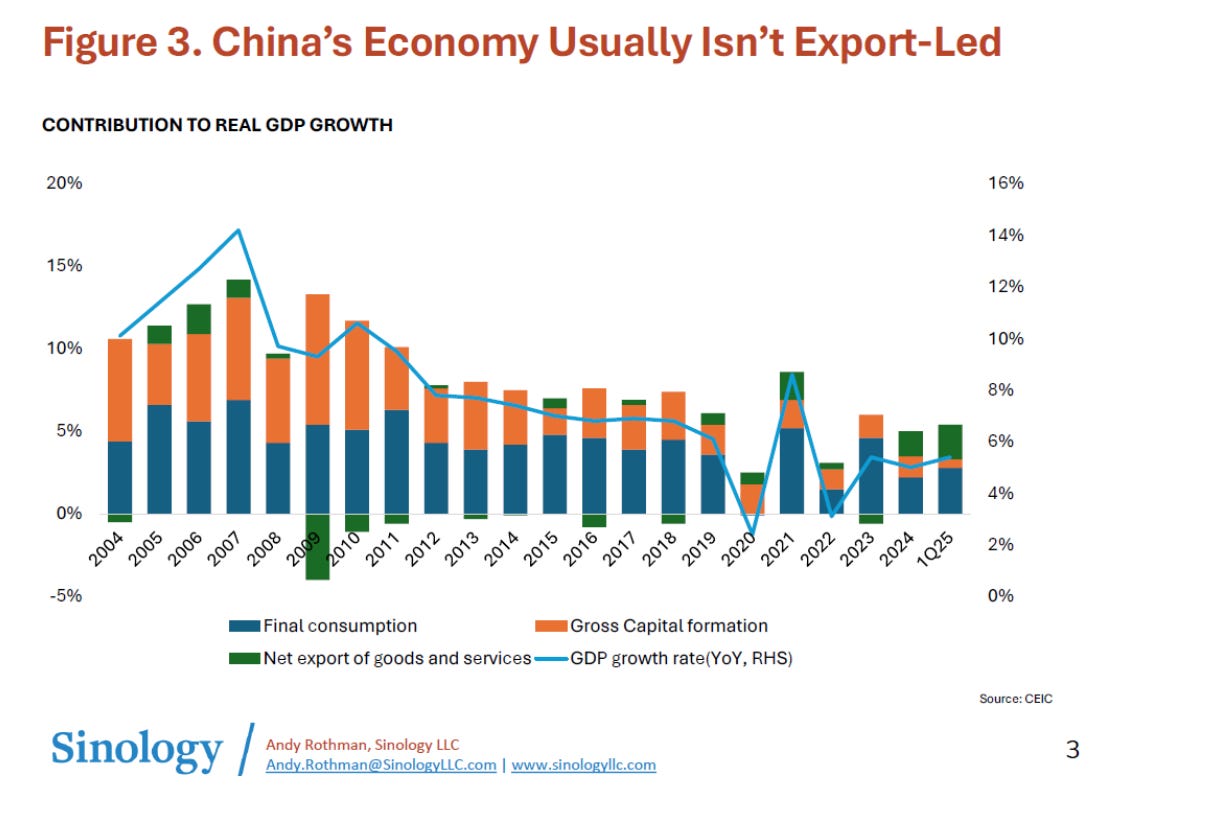

Today, the biggest China distraction is Trump’s tariff chaos. It’s a distraction because China’s economy is not usually export-led, and because the US only takes a small share of China’s exports.

In a later section of this report, I will explain why the tariff chaos is likely to be more painful for the US than for China, which is likely to lead Trump to retreat. Another section will explain why Trump’s policies, even in retreat, are likely accelerate and deepen reforms by Xi which will strengthen China’s domestic economy.

Trump has received a lot of bad advice from his team about China’s economy. For example:

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said, “China has no business model. Their business model is predicated on selling cheap, subsidized goods to the US.”

Secretary of State Marco Rubio said, “China is an example. I mean, it’s outrageous. I mean, they don’t consume anything. All they do is export and flood and distort markets.”

Stephen Miller, deputy White House chief of staff for policy, said, “China’s economy is completely dependent on its exports to the US and to the West.”

Peter Navarro, senior advisor to Trump for trade and manufacturing, and author of the 2011 book, Death By China, said, “If the Chinese vampire can’t suck the American blood, it’s going to suck the UK blood and EU blood.” He called on China to “stop being a predator to the world.”

The data, in fact, shows that domestic demand, not exports, is the biggest part of the Chinese economy, and that China is the world’s second largest and fastest-growing consumer market.

Exports are a relatively small part of China’s GDP. Economists focus on net exports, the value of a country’s exports minus its imports (because GDP measures domestic production). The net export share of China’s nominal GDP peaked at 8.5% in 2007 and was only 1.7% in 2017, before the first round of Trump tariffs. In 2023, net exports accounted for 2.1% of China’s GDP, compared to 4% in Germany, -1.5% in Japan, -2.9% in the US and — 0.6% in the UK. Over the last five years, on average, final consumption accounted for 56% of China’s GDP.

Exports are a relatively small part of China’s GDP growth. Another way to look at it is that between 2001 (when China joined the WTO) and 2019 (pre-pandemic), net exports on average were a negative 2.2% drag on real GDP growth. During that period of time, there were only three years in which net exports provided a significant, positive contribution to China’s GDP growth (2005, 2006 and 2019).

The net export contribution to GDP growth has been more volatile recently, due to global supply chain disruptions and slower domestic demand at home. In 2023, net exports were a -11% drag on growth, with 86% of growth coming from final consumption. Last year, however, consumption slowed significantly, and net exports contributed 30% of China’s GDP growth.

In the first quarter of this year, consumption remained weak, and net exports accounted for almost 40% of GDP growth. Final consumption contributed 52% of GDP growth, down from a 74% share in the first quarter of 2024. (The balance of growth came from gross capital formation.)

If we look at the five years through 2019, when domestic demand was healthy, on average, final consumption accounted for 64% of GDP growth, while only 1% of growth came from net exports.

All the president’s men are also wrong when they say that China “doesn’t consume anything.” Last year, China accounted for 10% of global imports, while the US share was 14%. (China’s share of global exports was 15%, and the US share was 8%.)

Last year, Chinese consumers bought twice as many cars as Americans, and in the first five months of this year, new energy vehicle sales rose 44% YoY.

China is the world’s second-largest consumer market, behind the US, and is the world’s fastest-growing consumer market. (I’ll talk more about consumption later in this report.)

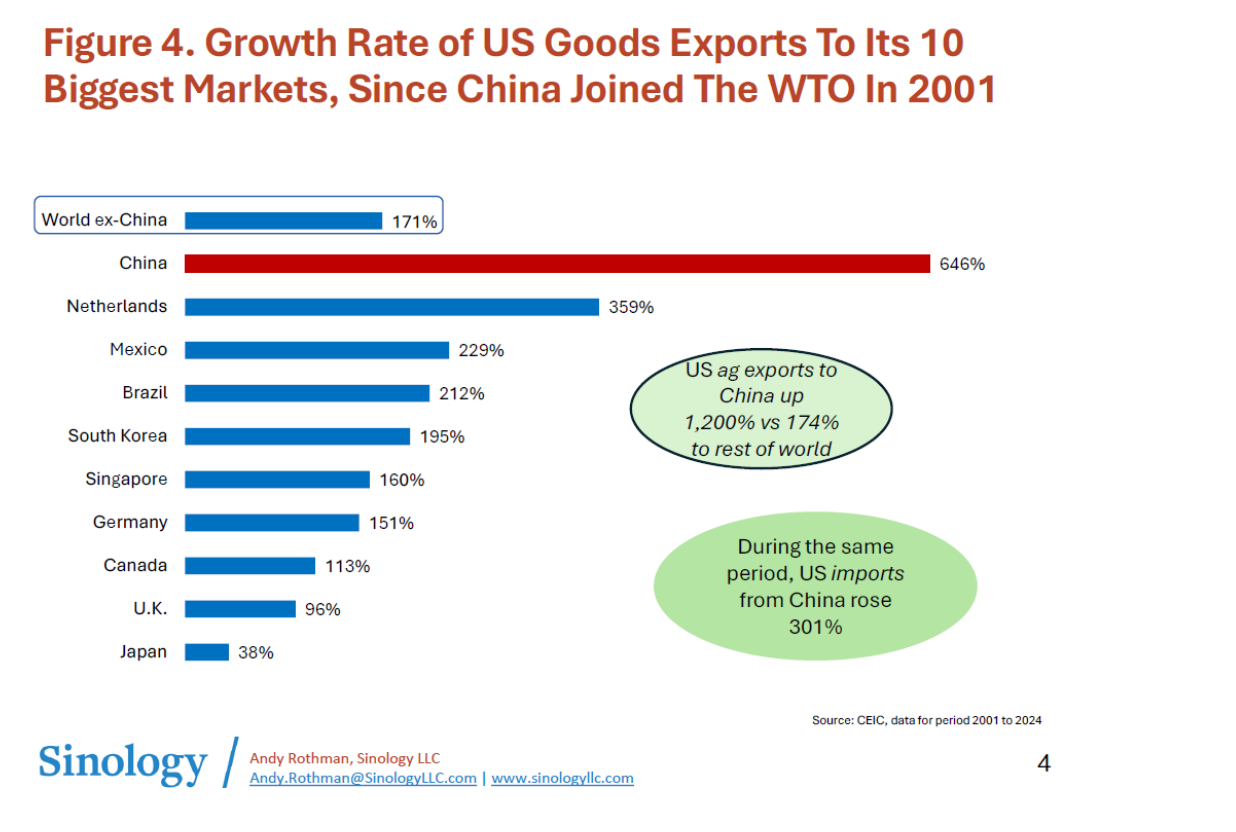

Trump recently posted, “Many years ago, we opened up the USA. Now, it’s time for China to open up – and that’s part of our deal.” Apparently, his staff has not told the president that China is the US’ third largest export market, after Mexico and Canada. And, while China has certainly not complied with all of its WTO commitments, it has opened its economy enough to be the fastest growing major market for American goods.

Since China joined the WTO in 2001, US exports to China are up 646%, while US exports to the rest of the world are up 171%.

American agricultural exports to China are up 1,200%, vs up 174% to the rest of the world.

During this period, US imports from China rose 329%.

Continued (and improved) access to China’s market is important to American farmers, ranchers and manufacturers, and to their employees.

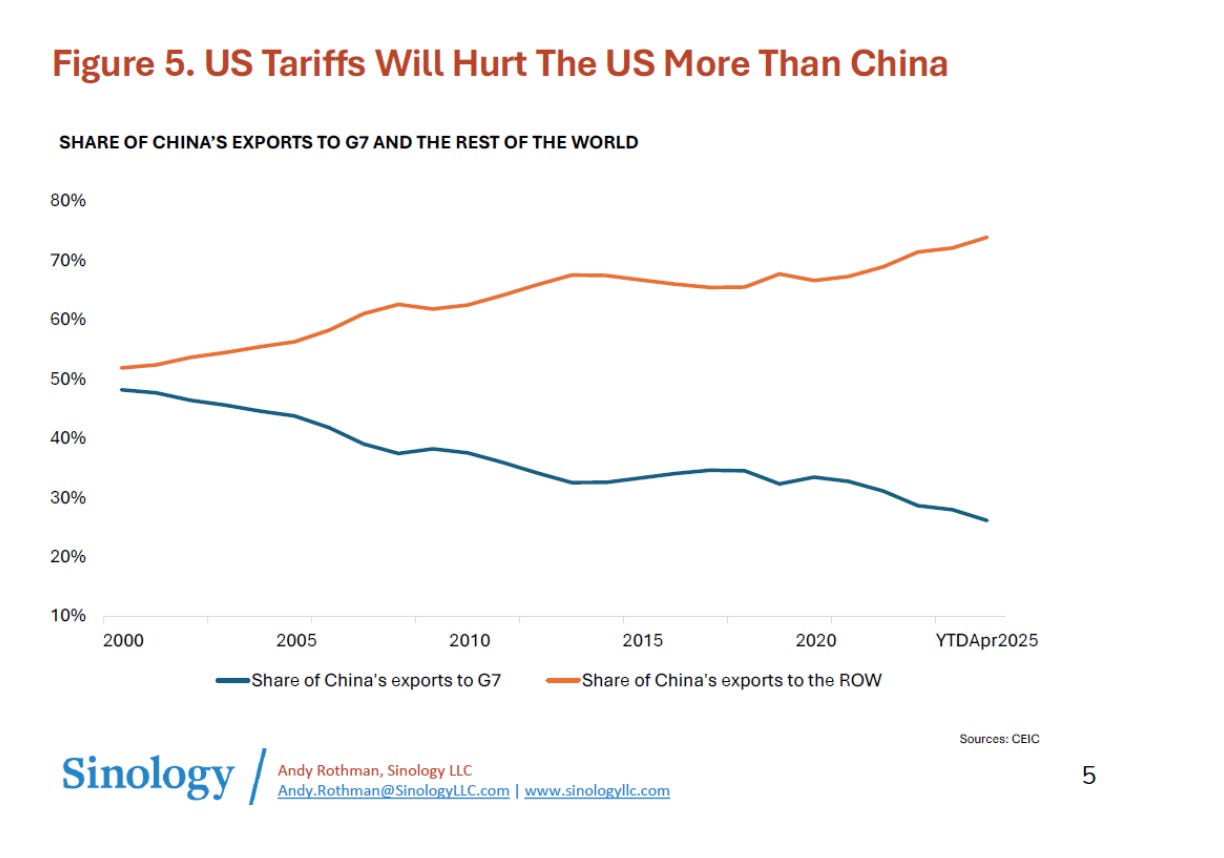

Another reason why the tariff chaos is a distraction rather than a key obstacle for Beijing is that China ships relatively little stuff to America.

Last year, only 15% of China’s total exports went to the US, equal to 2.8% of China’s GDP.

Chinese companies have been diversifying their overseas markets for many years, shifting from developed to developing markets. In 2000, the G-7 took 48% of China’s exports, but that share has fallen to only 26% this year.

About 150 mostly developing countries participate in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and those nations now account for about half of China’s exports.

In the first five months of this year, China’s largest trading partner was the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Exports to those countries, which are also BRI members, rose 14% YoY.

The EU was the second-largest trading partner, and China’s exports to the EU rose 8% YoY.

This explains why although Chinese exports to the US fell 28% YoY during April and May in response to tariff chaos, overall Chinese exports increased 6% during that period.

AVOID BEING DISTRACTED BY SHORT-TERM TARIFF CHAOS AND UNCERTAINTY

The first part of this report has been intended to persuade investors and corporates to avoid being distracted by headlines and focus instead on the longer-term opportunities in China.

Later in this report I will explain why I expect Trump to retreat from his tariff chaos. But, even if Trump does choose to attempt to decouple from China, with tariffs and restrictions on exports and visas, I expect four things will remain consistent:

I. China will remain the world’s second largest and fastest-growing consumer market. As I will explain in the second part of this report, pressure from Trump will lead Xi to accelerate and deepen policies to support private firms, which will result in more investment and jobs, and stronger wage growth, boosting consumption.

II. World-class competitors will continue to come from China. DeepSeek won’t be the last Chinese company to surprise foreigners. BYD sells more electric vehicles globally, and recently in Europe, than Tesla. CATL is the world’s top battery maker. DJI is the world’s leading drone manufacturer. And Mixue, which listed in Hong Kong recently, has more global beverage franchises than Starbucks.

III. China will remain a key part of global supply chains, for everything from rare earth magnets to pharmaceuticals. Last year, about 30% of big pharma deals with at least US$50 million up-front involved Chinese companies, up from none five years ago.

IV. China is likely to continue to account for more than 20% of global economic growth, larger than the combined share of growth from the US and its G-7 developed nation partners.

TRUMP WILL BLINK AGAIN

Trump has surrounded himself with China hawks.

It is clear that Trump has filled the senior ranks of his administration with China hawks. But Trump himself is not a China hawk. Will his hawks control China policy, or will Trump restrain them and focus on doing deals?

One hawk is White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller, who on May 1 said, “The reality is that we can either surrender economically to China or we can reclaim and reshore our manufacturing base and our industrial needs.”

A couple of weeks later, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Trade Representative Jamieson Greer met in Geneva with Chinese officials to de-escalate tariff tensions. In a joint statement by the two governments issued on May 12, they said they would be “moving forward in the spirit of mutual opening, continued communication, cooperation, and mutual respect.”

Trump’s hawks, however, didn’t get that message.

After the Geneva meeting, Marco Rubio, who theoretically heads foreign policymaking, as Secretary of State and National Security Advisor, said, “The era of indulging the Chinese Communist Party as it abuses trade practices to steal our technology and floods our nation with fentanyl is over.” He also pledged to “aggressively revoke visas for Chinese students.”

CIA Deputy Director Michael Ellis said, “China is the existential threat to American security in a way we really have never confronted before.”

Defense Secretary Hegseth told Congress, “Beijing is preparing for war in the Indo-Pacific as part of its broader strategy to dominate that region and then the world.”

Homeland Security chief Kristi Noem, also speaking after the Geneva meeting, announced she would “continue to hold Harvard University accountable . . . for coordinating with Chinese Communist Party officials on training that undermined American national security.”

FBI Director Kash Patel said the root of America’s fentanyl problem is the Chinese Communist Party, and “their long-term game is… to kneecap the US.”

The most active of the hawks has been Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick. In the weeks following the Geneva agreement to move “forward in the spirit of mutual opening… and cooperation,” Lutnick’s department has:

+ Disrupted US exports to China of the petrochemical feedstock ethane by requiring American producers to apply for licenses.

Suspended export licenses for the sale of parts and equipment used by Chinese nuclear power plants.

Halted sales (and support) to China of electronic design automation (EDA) software by American and European firms, by requiring new licenses for software used to develop and test semiconductors.

Issued guidance suggesting that global users of Huawei AI semiconductors could be subject to sanctions because those Chinese chips “were likely developed in violation of U.S. export controls.”

Halted shipments of US components and systems for China’s civilian aviation program.

Lutnick also told a U.S. Senator that even if Vietnam removed all of its tariffs and trade barriers, the Trump administration would not reciprocate, because Vietnam represents “a pathway from China to us.”

I still expect Trump ignore the hawks and blink again

Only six weeks after his April 2 self-proclaimed “liberation day,” Trump slashed his tariffs without any significant concessions from China. I expect him to blink again.

Trump presumably blinked in May because he understood that in the coming months, Republican households would rebel against rising prices for a wide range of consumer goods, and Republican factory owners would protest against high taxes for Chinese intermediate goods, which would lead to lower profit margins and layoffs.

The Geneva agreement cut the “liberation day” US tariffs on Chinese goods from 145% to 30% for three months, pending more negotiations. That still leaves US retailers and manufacturers (who use Chinese components and raw materials) facing continued uncertainty, and an effective, trade-weighted average tariff of about 40% on Chinese imports.

There are several factors which are likely to lead Trump to again back away from tariffs and export controls which would decouple the world’s two largest economies.

Tariffs and Decoupling Will Raise Inflation

It is clear that tariffs are taxes which will be borne by American consumers and companies, leading to higher prices and lower profits.

Ford has already raised prices on three of its models produced in Mexico, some by as much as $2,000. CEO Jim Farley noted that, “We have to import certain parts… like fasteners, washers, carpets… we can’t even buy those parts here.”

China is the top source of US imports of smartphones, laptops, lithium-ion batteries, toys and video game consoles. (Microsoft has already indicated it will raise the price of an Xbox Series X console from $499 to $599.)

“Virtually every car seat, stroller, bassinet and changing table sold in the US is made in China, making the children’s products industry among the most vulnerable to fast-rising costs and shortages,” the Washington Post reported.

Most syringes imported into the U.S. come from China, according to World Bank data. Nearly half of China’s exports to the U.S. are products for which the US has limited alternative external suppliers, according to the Australian central bank. Walmart CEO Doug McMillon warned investors that “even at the reduced levels, the higher tariffs will result in higher prices.”

The company’s CFO said, “We’re wired for everyday low prices, but the magnitude of these increases is more than any retailer can absorb. It’s more than any supplier can absorb. And so I’m concerned that the consumer is going to start seeing higher prices.”

The Fed, in its June 4 Beige Book report, found that “higher tariff rates were putting upward pressure on costs and prices. Contacts that plan to pass along tariff-related costs expect to do so within three months.”

The New York Fed said that it’s May survey found “nearly a third of manufacturers and about 45% of services firms fully passing along all tariff- 15 induced cost increases by raising their prices.” The NY Fed noted, “Consistent with textbook economics, tariffs generally resulted in higher prices to customers.” And, “Interestingly, a significant share of businesses also reported raising the selling prices of their goods and services unaffected by tariffs.”

Tariffs and Decoupling Will Lead to Lower Profits and Layoffs

Uncertainty about tariffs and the impact on the US economy is already having an impact on employment. ADP, the payroll processing company, reported that “the pace of hiring in May reached its lowest level since March 2023.”

Procter & Gamble, the world’s largest consumer goods company, announced in June that it will cut 7,000 jobs over the next two years.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics said that average monthly job gains in the first five months of this year was 124,000, down from an average of 168,000 in the same period last year.

An outplacement services firm reported that job cuts in May were up 47% YoY.

The June Fed Beige Book said “comments about uncertainty delaying hiring were widespread.”

The New York Fed said, “There were some signs that the sharp and rapid increase in tariffs affected employment levels and capital investments.”

GM said it anticipates tariff costs of $4-5 billion this year, potentially reducing its net profit by one-quarter. Apple CEO Tim Cook said tariffs will add $900 million to the company’s costs.

One factor that few recognize is that the tariffs hit industrial equipment and parts, as well as consumer goods.

China is the world’s largest exporter of machinery, and about 60% of its exports to the US are capital goods and parts, and industrial supplies. “China’s role as the dominant foreign supplier of industrial inputs to US manufacturing sectors is clear,” according to a 2023 study published by Brookings. This means that the Trump tariffs will raise costs for American factories.

The Richmond Fed recently identified 14 US counties that would suffer the most from the Trump tariffs (excluding retaliation by other countries), because they have higher employment in industries like textiles, agricultural support activities and apparel, “which are more reliant on imports from China.” I checked voting records from last November and found that Trump won all of those counties. Factory owners in those counties will soon be calling their representatives in Washington.

The tariff chaos explains why the World Bank on June 10 cut its forecast for US GDP growth this year sharply compared to six months earlier, to 1.4% from 2.3%. The Bank, however, left its China GDP growth forecast of 4.5% unchanged.

The Rare Earth Dilemma

Another issue that recently drew Trump’s attention, and which will cause him to blink again, is that U.S. industry, especially defense contractors, are heavily dependent on imports of critical minerals and key finished products such as magnets from China. At this point, there are few alternatives, foreign or domestic, for many of these items. Apparently, the Trump administration failed to consider that China might hold up shipments of the minerals, and the magnets made from them, to gain negotiating leverage with him.

The International Energy Agency reports that critical minerals are important to “a broad array of industrial and technological applications. From AI and robotics to high-performance materials and aerospace, these minerals’ contribution to industrial and technological development is increasing, with broad economic implications.”

The IEA also finds that “China is the dominant refiner for 19 of the 20 minerals analyzed, holding an average market share of around 70%.” To illustrate the importance of these minerals, let’s look more closely at two, dysprosium and gallium.

“Dysprosium is a rare earth metal that is used in the production of powerful neodymium iron boron (NdFeB) magnets, which are used in applications such as electric vehicle motors, wind turbine generators, consumer electronics, industrial motors,” according to the US Department of Energy. Dysprosium is also used to make high-performance alloys and advanced ceramics, which are used in applications requiring high thermal resistance and durability, like jet engines and space exploration equipment.

“Gallium plays a critical role in energy applications such as LEDs, solar panels, power electronics, and permanent magnets,” according to DOE. Gallium is used in the production of specialized semiconductors that are incorporated into missile defense and radar systems, including Patriot missiles, as well as electronic warfare and communications equipment.

DOE reports that China is responsible for 93% of global refining of dysprosium and 97% of global gallium refining.

China also dominates global production of rare earth element magnets, with a 92% market share. These magnets are, according to the US Department of Defense, “essential components in a range of defense capabilities, including the F-35 Lightning II aircraft, Virginia and Columbia class submarines and unmanned aerial vehicles.”

Overall, DOD requires about 9,200 pounds of rare earth materials for each SSN-774 Virginia-class submarine, and 920 pounds for each F-35 stealth fighter.

In response to the Trump tariffs, Beijing has established a new export licensing system for critical minerals and magnets, which has been used to retaliate against US export controls and which presents a huge problem for American manufacturing, including weapons production.

Some importers of these magnets, including American automakers, have reported recent problems with sourcing from China. Ford CEO Jim Farley on June 13 said “It’s day to day. We’ve had to shut down factories. It’s hand-to-mouth right now.” He said applications to import magnets “are being approved one at a time” by China’s Ministry of Commerce.

This explains why Trump raised the issue of rare earth element magnet exports in his June 5 call with Xi. Trump said that as a result of the discussion, “there should no longer be any questions respecting the complexity of rare earth products,” and he claimed Xi had agreed to resume exports. Trump didn’t provide any details, and Beijing has not commented, although there are reports that some licenses have been approved for exports of critical minerals and magnets. Clearly, Beijing will continue to use exports of these materials for leverage in negotiations with Trump.

Trump Doesn’t See China As A National Security Risk

Another reason I expect Trump to blink again on tariffs and decoupling is that he does not seem to share his hawks’ concerns about the threat from China.

Trump tends to speak in relatively positive and constructive terms about Xi and China:

We had a very good conversation with President Xi . . . I think we’re in very good shape with China and the trade deal . . . Trade can bring greater friendship with China . . . I have a very good relationship with President Xi, and I think it’s going to continue . . . The relationship is very good. We’re not looking to hurt China. . . Chinese students are coming, no problem. It’s our honor to have them, frankly.

The president’s rhetoric about China is the opposite of what his hawks say.

And, Trump says he is opposed to the U.S. imposing its ideas about governance on other countries. In Riyadh in May, Trump said,

“This great transformation [in the Middle East] has not come from Western interventionists… giving you lectures on how to live or how to govern your own affairs. Instead, the birth of a modern Middle East has been brought about by the people of the region themselves... developing your own sovereign countries, pursuing your own unique visions, and charting your own destinies… In the end, the so-called ‘nation-builders’ wrecked far more nations than they built — and the interventionists were intervening in complex societies that they did not even understand themselves.”

Presumably, Trump is also disinclined to use the sanctions, export controls and other tools at his disposal to promote democracy and regime change in China.

Trump Sees Export Controls As Negotiating Leverage

Finally, in my view, Trump — unlike past presidents — views export controls as form of negotiating leverage, rather than as a critical tool to protect national security. He is likely to retreat from key export controls put in place recently by his hawks, if they get in the way of reaching a grand trade deal with Xi.

During his first term, Trump cancelled serious sanctions imposed by his Commerce Department against ZTE, a Chinese telecommunications equipment maker. The Commerce Department had banned US companies from selling components to ZTE for seven years because it had violated the terms of a settlement deal for illegally shipping goods made with US parts to Iran and North Korea. The ban might have crippled ZTE.

Trump reversed it, saying, "ZTE, the large Chinese phone company, buys a big percentage of individual parts from US companies. This is also reflective of the larger trade deal we are negotiating with China and my personal relationship with President Xi.”

During his first term, Trump also reversed course – albeit only temporarily – on Huawei, one of China’s leading tech companies, again highlighting sales by U.S. firms.

"One of the things I will allow, however, is, a lot of people are surprised we send and we sell to Huawei a tremendous amount of product that goes into the various things that they make. And I said that that's okay, that we will keep selling that product. . . I've agreed to allow them to continue to sell that product. So American companies will continue and they were having a problem, the companies were not exactly happy that they couldn't sell because they had nothing to do with whatever it was potentially happening with respect to Huawei, so I did do that."

More recently, Trump has reversed course on his sanctions on TikTok. During his first term, Trump signed an executive order saying the US “must take aggressive action against the owners of TikTok to protect our national security.” Since returning to the White House in January, however, Trump has twice deferred enforcement of a law banning TikTok or forcing sale of the app.

In May, rather than call the app a national security threat, Trump said, “I have a little warm spot in my heart for TikTok,” because it helped him win re-election. “No Republican ever won young people, and I won it by 36 points, and I focused on TikTok.”

Now that Elon Musk is gone from the White House, it’s also possible that Trump will be influenced another American tech leader, Jensen Huang, founder and CEO of Nvidia. Recently, Huang has been an outspoken opponent of US export controls designed to handicap China’s tech industry.

Huang argues that these controls are counterproductive:

“The U.S. has based its policy on the assumption that China cannot make AI chips. That assumption was always questionable, and now it’s clearly wrong.”

“China’s AI moves on with or without U.S. chips. Export controls should strengthen U.S. platforms, not drive half of the world’s AI talent to rivals… I think all along the export control was a failure.”

Huang also says that blocking Nvidia and other US tech firms from the China market will have negative consequences for American innovation:

“Losing access to the China AI accelerator market, which we believe will grow to nearly $50 billion, would have a material adverse impact on our business going forward and benefit our foreign competitors in China and worldwide.”

The day after the U.S.-China talks in London concluded, Lutnick admitted (for the first time that I’m aware of) that he was using “national security” export controls as a bargaining chip. On CNBC, Lutnick said that when Beijing began “slow rolling” export licenses for rare earth magnets, “we started putting on our countermeasures, right? We cut planes, ethanol, Marco Rubio put out that students may not be able to come to America… we were at mutual assured annoyance, if you will.”

Export controls, which hurt US companies, for the purpose of “mutual assured annoyance,” according to Lutnick.

So much for the official statements that restrictions on exports to China and on visas for Chinese students were designed to address vital national security concerns. Clearly, Trump sees everything as part of a deal.

Finally, Trump must be feeling significant political pressure to sign a trade deal with someone. Anyone. Even China.

Twenty days after his April 2 “Liberation Day” press conference, Trump said, “I’ve made 200 deals.” Asked when those deals would be announced, he replied, “I would say, over the next three to four weeks, and we’re finished, by the way.”

As of June 16, Trump had not announced even one comprehensive trade deal, although he did sign an executive order implementing a very limited agreement with the UK, covering only imports of British autos and airplane parts.

Of course, predicting what Trump will do on any issue on any day is difficult. But, for the reasons discussed above, I think it is likely that Trump will focus on being dealmaker-in-chief and try to reach a broad agreement with Xi.

However, as I will explain in the next section of this report, regardless of whether Trump and Xi sign a trade deal, the actions of Trump’s hawks will lead Xi to accelerate and deepen his policies to re-embrace China’s private sector and boost domestic demand.

Deal or no deal, Donald Trump will help Xi make China great again.

XI’S PROBLEMS

Part of Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” strategy seems to have been based on the idea that China’s economy was tanking. In May, Trump said, “China’s getting killed right now. They’re getting absolutely destroyed. Their factories are closing. Their unemployment is going through the roof. I’m not looking to do that to China. . . And they want to do business very much. Look, their economy is really doing badly. Their economy is collapsing.”

China’s economy does face significant challenges, but it is not collapsing.

Macro data for the first quarter of this year was, in fact, decent. Real household income rose 5.6% YoY and real consumption spending was up 5.3% YoY. China’s new energy vehicle sales were up 44% YoY during the first five months of 2025. Electricity consumption, a good proxy for industrial activity, rose 3.1% YoY during the first four months, and was 38% higher than during the same period in 2019.

These growth rates are high relative to most developed countries, but they are considerably slower than what China experienced a decade ago, so are disappointing to most Chinese.

Even after Trump pushed tariffs up to extreme levels, the IMF forecasts that China will have the second-fastest GDP growth rate (after India) of all major economies this year and next, which will see China account for more than 20% of global growth, a larger share of global growth than from the US and the rest of the G-7 nations combined.

There is, of course, a long list of problems, starting with the residential property market. I estimate that home prices are down about 25% from their 2021 peak, and sales are anemic in most cities. Still, the property problems are not as severe as those during the US housing crisis, largely because most Chinese buyers were required to put down 30% cash, far from the median cash downpayment of 2% ahead of the US crash. (Since September 2024, the minimum downpayment in China was reduced to 15%.) Few Chinese homeowners are underwater on their mortgages. Nonetheless, the property market will not return to its leading role in China’s economy.

Another problem is that inflation is too low. In May, CPI fell 0.1% YoY, although falling energy prices (down 6.1% YoY) accounted for most of that weakness. Core CPI (excluding more volatile food and energy prices) was healthier, up 0.6% YoY in May, and improving. Core CPI was up an average of 0.12% MoM over the last six months, while in the prior six months, Core CPI fell by an average of -0.03% MoM. Nonetheless, weak inflation reflects weak consumer sentiment and spending.

A sky-high unemployment rate (16% in April) among young people (ages 16-24) is another important problem.

The root of all of these problems is that China’s entrepreneurs and consumers are pessimistic about the economic outlook and have low confidence in their government’s management of the economy.

A survey of consumer confidence, published monthly by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, is at all-time lows. (Figure 6 also illustrates that Beijing does release some quite negative economic data.)

Confidence among entrepreneurs has been weak for several years because of doubts about Xi’s support for private companies, tensions in the US-China relationship and, most importantly, because of a series of chaotic and counterproductive regulatory policy changes which upended many sectors.

The most important policy mistake was made in the summer of 2020, when Xi’s government announced new residential property policies, referred to as “the three red lines,” which inadvertently tipped the housing market into recession. New home sales (on a square meter basis) fell 27% YoY in 2022, then fell another 8% YoY in 2023, and dropped 24% YoY during the first four months of 2024, before Xi finally announced adjustments to his housing policies on May 17.

Waiting a few years too long to fix the property policy mistake caused house prices to fall, many developers to fail, and the loss of construction jobs as new home starts froze. These property policy failures have been a key factor behind the loss of confidence among consumers and entrepreneurs. Moreover, about 60% of household wealth is in family homes, so falling prices have undoubtedly left consumers wanting to save more and spend less.

Xi made similar policy mistakes in regulating internet platforms, the video gaming industry, and for-profit education companies.

The sectors hit the hardest by Xi’s policy mistakes were dominated by privately-owned companies. This damaged the confidence of most entrepreneurs, which had a dramatic effect on the economy, since small, entrepreneurial private firms account for almost 90% of urban employment, which means that most consumers are either entrepreneurs or work for a private company. When entrepreneurs didn’t have the confidence to invest in or hire for their businesses, wage growth slowed, as did consumer spending.

Between 2008 and 2019, the real compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of final consumption in China was 8.3% (vs. US consumption growth of 1.7%). But the collapse of confidence led the CAGR of consumption to fall by almost half, to 4.6% between 2020 and 2023 (while it accelerated in the US to 2.6% during that time).

This consumption slowdown is why net exports accounted for an unusually large share of China’s economic growth last year and in the first quarter of this year. Xi needs to get the composition of growth back to where it was before his policy mistakes, led by consumption.

Why Did Xi Make These Policy Mistakes?

In speeches introducing his new regulatory policies, Xi did not discuss ideology. Rather, he indicated that his policies were intended to address many of the same socio-economic concerns that democracies are wrestling with, from income inequality to unequal access to education and health care and housing affordability. These are increasingly serious problems in China.

Xi’s policies may have been well-intentioned, but they were poorly thought out and chaotically implemented. The socio-economic problems were not improved, and unintended consequences damaged many small businesses, crashing entrepreneurial and consumer confidence, dragging down the pace of economic activity.

Was It Ideological?

An important factor in assessing whether Xi can correct his policy mistakes and restore confidence is understanding why he made those mistakes.

As I just explained, my view is that Xi was attempting to address the socioeconomic problems that were the byproduct of decades of rapid economic growth.

Some foreign observers, however, believe Xi’s policy decisions were based on his ideological beliefs, not on solving problems. These observers argue that after becoming Party chief in 2012, Xi decided that markets and private companies had advanced too far in China, and needed to be scaled back and made more subservient to state-owned companies and central planning.

If an investor or corporate director takes that view, it is easy to reject the premise that Xi recognizes his policy mistakes and will course correct.

But, I do not believe there is evidence to support the view that Xi is ideologically opposed to private firms and markets.

Xi’s Political Career Rose With China’s Entrepreneurs

Xi surely understands that the success of China’s entrepreneurs and the rise of markets is why the Communist Party has remained in power for so long. In fact, Xi was present at the creation of markets, because he worked in some of China’s most entrepreneurial places during his long career, and his late father, Xi Zhongxun, oversaw the early reforms in Guangdong, from 1978 to 1980.

Observers who only started following China in recent years may not recognize how dramatic the changes have been since that time. When I first worked in China in 1984, as a junior American diplomat, there were no private companies – everyone worked for the state. (During that time, Xi was a Party official implementing reforms in a poor region of Hebei Province.) Today, as noted earlier, almost 90% of urban employment is in small, privately owned, entrepreneurial firms.

Rhetorical Support For Entrepreneurs

Xi often voices support for the remaining state-owned enterprises (SOEs). But he also says he wants to “enhance the ability to get rich,” and that “small and medium-sized business owners and self-employed businesses are important groups for starting a business and getting rich. . . It is necessary to protect property rights and intellectual property rights, and protect legal wealth.”

Xi has said that “we will see that the market plays the decisive role in resource allocation,” and “we will support capable private enterprises in leading national initiative to make breakthroughs in major technologies,” and that he wants to “promote entrepreneurial spirit.”

Private Sector Has Grown Under Xi

Talk is cheap. What is more convincing is that private firms have continued to thrive since Xi became Party chief in 2012.

Under Xi, private firms have continued to drive all net, new job creation. The private sector share of total urban employment has risen from 82% in 2012 to 89% in 2023.

Trade, too, is dominated by entrepreneurs. In the first five months of this year, domestic private firms accounted for 65% of the value of exports, up from a 38% share in 2012 and only 7% in 2001.

The number of private firms increased by more than four-fold since 2012. In the first quarter of this year, 2 million new private firms were established, an increase of 7% YoY, faster than the average growth rate over the past three years.

In 2012, private companies accounted for less than 50% of national tax revenue, a share that is now about 60%.

Xi’s New Economic Strategy Depends On Private Firms

Xi has recently promoted an economic strategy focused on “new-quality productive forces,” which depends on the success of China’s entrepreneurs. This strategy, Xi has said, depends on “disruptive technology . . . to give birth to new industries. . . that are characterized by high technology, high performance and high quality.”

Xi is clearly counting on the success of private firms, which account for 90% of China’s high-tech companies and which dominate the industries Xi is promoting: batteries, electric vehicles, and artificial intelligence. Thirteen of the 15 globally significant Chinese battery makers are privately owned; seven of the top 10 electric vehicle makers (by number of units produced), are privately owned; and all of the eight leading AI startups are privately owned.

If The Problem Isn’t Ideological, Why Hasn’t Xi Fixed It?

Over the last 12 months, some of Xi’s failed and disruptive policies have been reversed. Often quietly, sometimes partially. Some industries have recovered, such as internet platforms and video gaming. Real estate has stabilized a bit, although at a very weak level. Xi has also begun reembracing entrepreneurs, but has yet to reignite their confidence.

In my view, stubbornness, rather than ideology, has been the problem.

Xi has often demonstrated that he can be obstinate, taking too long to change failed policies. His “zero-COVID” policies, for example, were very effective during the early phase of the pandemic but failed as new variants of the virus began to circulate. Xi stubbornly refused to change his approach to COVID, including at the 20th National Congress of CCP in October 2022, despite strong public opposition and significant economic damage. Finally, a month after that meeting, with social tensions rising, he changed course and ended zero-COVID, reopening the economy.

What Xi Will Do Next

In the coming quarters, I expect Xi to overcome his stubbornness by taking the following steps:

Restore confidence in government policymaking, making clear that it will be more predictable so businesses can plan, invest and hire.

Announce plans to respond to the possibility that the Trump tariffs will remain in place at a prohibitively high level. Even though only 15% of China’s exports go to the US, a sudden and sharp decline in this trade will be disruptive and threaten a significant number of jobs. The government plans should focus on helping small businesses that export to the US avoid layoffs.

Re-embrace the private sector. Entrepreneurs must have confidence that Xi wants them to thrive.

Encourage consumption, with rhetoric and policies, ranging from a stronger social safety net to changes in the tax code. Promoting advanced production is fine, but the reality is that given the external political tensions, there must be domestic demand for EVs, batteries and AI, even if Trump retreats from his tariff push. Newer sectors cannot thrive on exports.

Why Xi Will Do It

Xi will take these steps in the coming quarters because he has no choice.

The current economic climate will not support enough growth and enough job creation. The economy is not collapsing, but it is growing at a pace which is disappointing for most Chinese. The longer Xi waits to make serious changes, the deeper this disappointment will become.

Unless Xi also makes these policy changes, he risks failing to accomplish the ambitious economic development (and political) goal he announced in 2020, to double China’s GDP or per capita income by 2035.

And forget about observers who claim that Xi is only interested in national security, not economics. It is impossible to believe that Xi doesn’t understand that the biggest threat to China’s security would be a weak economy. (This, of course, applies to most countries.)

Bold But Not Revolutionary

The policy changes outlined here are bold, but they are far from revolutionary. Appropriate for a Chinese Communist Party that long ago transitioned from a revolutionary organization to a ruling party focused on development and stability.

Xi is well aware that his predecessors in post-Mao China succeeded with bold economic policy changes. When I first visited China as a student in 1980, it was poor, with per capita GDP less than Afghanistan and Haiti. Now it is the world’s second largest economy, with a thriving middle class. This came about because the Chinese people are incredibly resilient, bouncing back from obstacles put in front of them by their own and foreign governments. And because the Party has been increasingly pragmatic with respect to economic policy.

The first bold, pragmatic step was in 1978, when Deng Xiaoping chose economic growth over class struggle by “seeking truth from facts.”

In 1992, when the economy was in terrible shape, Deng’s “southern tour” — a train trip to encourage entrepreneurs — boosted private firms, kicking off two decades of average annual double-digit GDP growth.

In the late 1990s, Jiang Zemin and Zhu Rongji sacked 46 million workers at state-owned firms, privatized the housing market and began serious negotiations to join the WTO.

In the early 2000s, Jiang invited entrepreneurs to join the Party, emphasizing that the Party’s primary goal is economic development.

Xi’s contribution will be bold, but evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, building on these earlier policies.

Alice Miller, a longtime analyst of China’s domestic politics, including at the CIA from 1974 to 1990, in an essay published this month, reminded us that the Party’s “legitimacy rests on its ability to deliver economic gains for all of society. . . The supposed bargain is that if the Party delivers economic progress, China’s society will acquiesce to the Party’s grip on power.” Miller explains that “the origin of this bargain actually reverts to the 1978 Third Plenum . . . [and] each successive leadership has not sought to over-turn the reform framework launched by Deng Xiaoping, but to sustain it by setting new goals and addressing side-effects of its success.”

For Xi, re-embracing entrepreneurs is relatively easy and uncontroversial, given that private firms already drive all of the growth in jobs, innovation and wealth.

Promoting consumption equally with production is also relatively easy and uncontroversial, given that final consumption already accounts for 56% of China’s GDP, and, in the five years before the pandemic, consumption contributed an average of 64% of GDP growth. For many years, consumption in China has grown far faster than in the U.S.

China’s leaders, including Xi, have been supporting consumption by raising the minimum wage more than fivefold over the last 20 years. (In comparison, the U.S federal minimum wage increased only 40% during that period.)

The Process Is Underway

As noted earlier, most Chinese consumers either work for entrepreneurial firms or are themselves entrepreneurs, so restoring confidence in the private sector is the most important step.

Xi has already begun re-embracing entrepreneurs.

On February 17, Xi held a high-profile meeting with leading entrepreneurs. Addressing an audience which included Alibaba’s Jack Ma, as well as leaders of DeepSeek, CATL, BYD, Tencent, Xiaomi, Huawei and Unitree Robotics, Xi said, “It is time for private enterprises and private entrepreneurs to show their talents” and that his government “must resolutely remove various obstacles” faced by private firms.

According to China’s official media, Xi seemed to acknowledge that recent regulatory policies were key obstacles, saying that they were “temporary rather than long-term, and can be overcome rather than unsolvable.”

In March, a joint statement by the leadership of the Party and the government announced a “special action plan to boost consumption.” There were few details, but the language suggested that promoting domestic demand has become Xi’s top political priority.

In May, a new Private Economy Promotion Law came into effect, after being passed on an accelerated timeframe by the National People’s Congress. One important element of the law is protection against abuse of power by local government officials, who, in recent years, have sought to collect unauthorized fees from private firms to compensate for declining tax revenue.

The law has been touted by the official media, and at a press conference, a Justice Ministry official said the law “fully demonstrates the Party Central Committee’s firm determination to promote the development and growth of the private economy.”

According Jamie Horsley, a senior fellow at Brookings and former executive director of the Yale China Law Center, the new law won’t “completely resolve the many challenges facing the private sector in China,” but “its impact lies in serving as a political statement of the CCP’s intent to better ensure China’s private firms continue to invest, hire, train, innovate and otherwise contribute to the country’s socioeconomic development.”

More Is Needed, And Trump Will Help

This progress is encouraging, but is far from sufficient. Confidence and economic activity has yet to rebound.

In my view, in the coming quarters, Xi will overcome his inherent stubbornness and take the steps necessary to persuade Chinese entrepreneurs that he supports them, as Deng did on his during his 1992 train trip.

Xi will not proclaim, “To get rich is glorious,” as Deng is reputed to have said, but I do expect Xi to say and do enough to restore confidence in his economic policy management. Xi has no alternative.

And Donald Trump will help him get the courage.

First, because Trump’s use of tariffs and restrictions on exports and student visas has made clear that China’s economic future must be based on domestic demand, not markets in countries where leaders are nervous about Beijing’s rising clout.

Even if Trump and Xi work out a deal that avoids economic and technological decoupling, the new global environment is clear.

Second, for a leader who may be reluctant to make policy course corrections to avoid appearing to acknowledge mistakes, Trump offers the opportunity to say that policy changes are designed to respond to Washington, rather than clean up at home.

Is Restoring Confidence Enough?

The collapse in confidence has led families to save rather than spend and invest in their own firms. Family bank balances have increased 95% from the start of 2020. The net increase in these household bank accounts, which include accounts for many small family businesses, is equal to US$ 10.8 trillion, which is more than double the size of Japan’s 2024 GDP, and almost double the value of China’s pre-COVID 2019 retail sales. This could be significant fuel for a rebound in hiring and investment by small firms, which could lead to a rebound in consumer confidence and spending, as well as a potentially sustainable recovery in mainland equities, where domestic investors hold more than 95% of the market.

Pragmatism Will Prevail

I understand that some will be skeptical about the policy changes that I’ve forecast in this paper, because they believe that since becoming Party chief, Xi has discovered an ideological aversion to the entrepreneurial firms that have made China rich and kept the Party in power. As I’ve explained, I don’t see evidence to support that perspective.

For me, the most compelling reasons to be optimistic are my belief in the resilience of the Chinese people, and in the economic policy pragmatism of the government.

Many of the entrepreneurs I’ve recently met in cities such as Xiamen, Hefei, Nanjing and Shanghai were struggling, but they had not given up.

Many of the government policies implemented since 2020 have created more problems than they solved.

Since last fall, however, the policy pendulum slowly began swinging back towards course correction.

I believe this process will accelerate and deepen for three reasons.

First, Xi Jinping has no choice. Bold policy changes are necessary to put the Chinese economy back on track, and a strong economy has been central to the Party’s rule since 1978. I think Xi understands this and is pragmatic enough to take steps sufficient to support private firms and consumption. He isn’t an ideologue.

Second, Trump’s efforts to constrain China’s growth and isolate its tech sector make clear that, even if Trump backs down from his tariff threats, Xi must rely on his own 1.4 billion consumers, not foreigners, to support economic development.

Third, Washington’s efforts to kneecap China’s economy provide Xi with a ready excuse for fixing his own policy mistakes — he can blame Trump.

Pragmatism indicates that these policy changes will be rolled out over the coming quarters, and resilience (as well as huge household savings) suggests the economic impact might be swift.

Andy Rothman

Andy.Rothman@SinologyLLC.com

If only we could get facts in front of more Americans...let alone these idiots who have become elected and political leaders, pundits...oh wait. I forgot. We live in a post-factual society, now. Post-reason, post-everything except "America is great again."

Thanks for the excellent article! I agree with most, and I just hope you are right with your assessment that Mr. Trump isn't a committed China hawk and that Mr. Xi isn't a committed enemy of private business. Would be great! But there is also another version, namely that Mr. Xi's recent change in rhetoric away from preventing the "disorderly growth of capital" towards a more friendly attitude to private business has been less a Damascene conversion but rather due to some outside pressure from powerful party elders unhappy about their loss on investments. E.g. the Nikkei's Mr. Nakazawa has been promoting that story for some time. In a same vein, some Republican donors may also have whispered to Mr. Trump that he shouldn't quite forget capital markets.