"Turning their back on their own people" — Phrase of the Week

China's new K-Visa sparks concern at home

Our phrase of the week is: “turning their back on their own people” (胳膊肘往外拐 gēbo zhǒu wǎng wài guǎ)

Context

China’s new K-visa is sparking fierce debate online.

Launched on October 1, the visa makes it easier for young science and tech professionals from abroad to stay in China for up to five years without employer sponsorship.

While the policy was quietly announced in August, it exploded into public consciousness this month.

This follows Indian media outlets comparing it to America’s H-1B visa — positioning the K-visa as an attractive alternative now that the US has tightened its immigration rules.

That comparison hit a nerve in China.

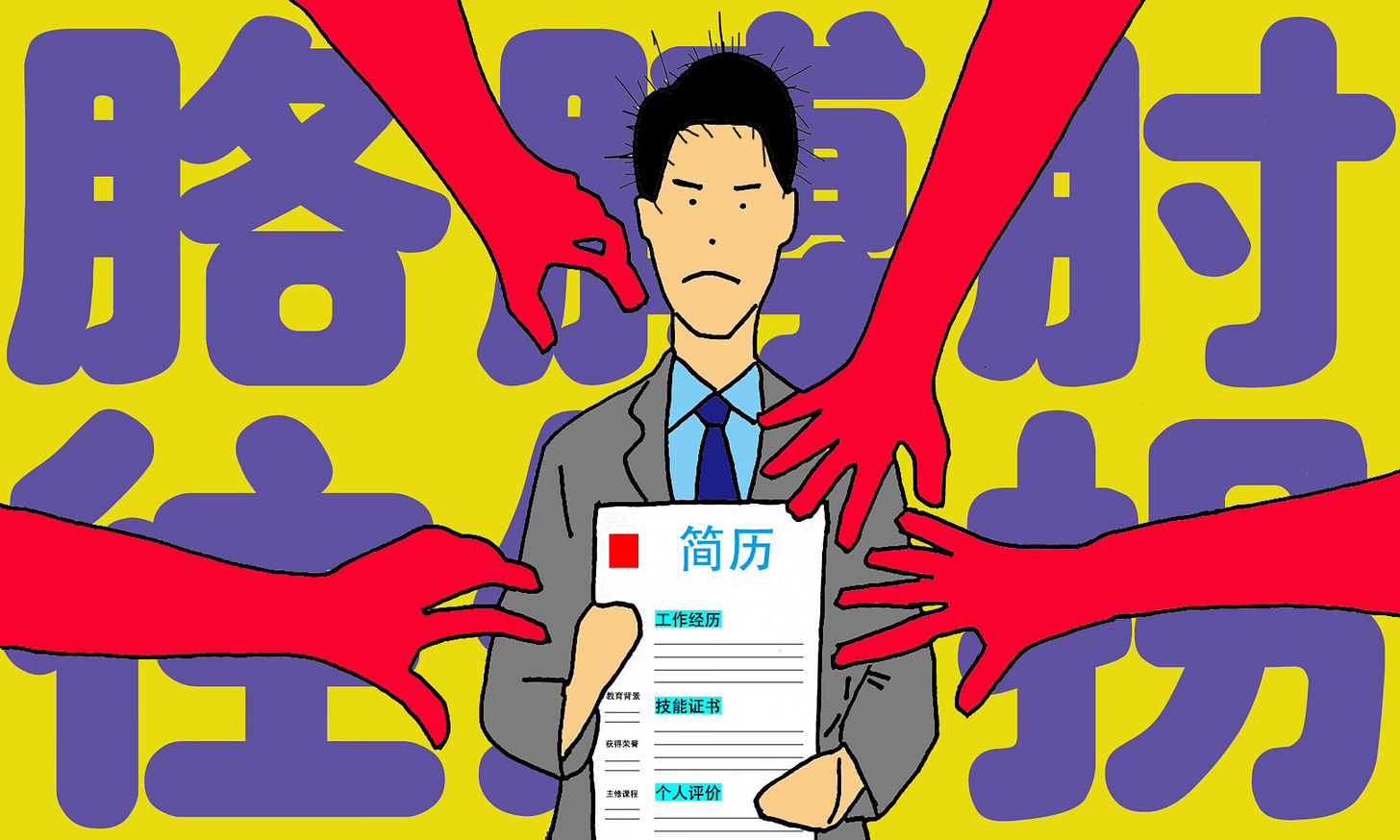

With youth unemployment at 19% and a record 12.2 million college graduates competing for jobs this year, many young Chinese people view the policy with suspicion. And details about the new visa are still scant, fuelling fears online.

The core complaint is that China is prioritising foreign talent over its own struggling youth. This sentiment is captured perfectly in one phrase that’s been circulating widely in the media:

“Young Chinese who are anxious about job prospects find this policy hard to comprehend and perceive it as an act of the government turning its back on its own people.”

在正愁找不到工作的中国年轻人眼里,仍然会是难以理解的”胳膊肘往外拐”政策。

zài zhèng chóu zhǎo bú dào gōngzuò de zhōngguó niánqīng rén yǎnlǐ, réngrán huì shì nányǐ lǐjiě de “gēbo zhǒu wǎng wài guǎi” zhèngcè.

What it means

“Turning its back on its own people”, or literally “elbows bending outward” (胳膊肘往外拐), is a common colloquial Chinese phrase.

It’s used to criticise someone for favouring outsiders over their own people or family, suggesting disloyalty or acting against the interests of them and the group they belong to.

The phrase uses anatomy to make the point: elbows naturally bend inward, not outward.

According to some sources, the phrase first appeared in Jin Ping Mei (金瓶梅), a famous Ming Dynasty novel written by an anonymous author known as Lanling Xiaoxiao Sheng (兰陵笑笑生).

In Chapter 81 of the novel, a servant defending his loyalty to the household says:

“I don’t mean to talk down to you, but you’re still young and don’t understand how things work.

Do you think I would bend my elbows outward? It would be better to just sell it off and be done with it.”

我不是托大说话,你年少不知事体。我莫不胳膊儿往外撇?不如卖吊了,是一场事

Wǒ bú shì tuō dà shuōhuà, nǐ niánshào bù zhī shìtǐ. Wǒ mò bù gēboer wǎng wài piě? Bùrú mài diào le, shì yī chǎng shì.

The servant uses the phrase “elbows bending outward” (胳膊儿往外撇) to insist he’s not cheating the family in his business dealings.

It’s a metaphor to express he is loyal to the family.

By the Qing Dynasty, the expression had evolved into its modern form with a different character meaning to “turn” or “bend” (拐 guǎi replacing the more classical 撇 piě).

It spread widely, particularly in northern China. And today it’s commonly used in family disputes and workplace conflicts to criticize those who protect outsiders’ interests while neglecting their own group.

In the context of the K-visa, some young Chinese people view the policy as the government “turning its back on its people” — helping foreign professionals access opportunities while domestic youth face fierce competition for scarce jobs.

Andrew Methven is the author of RealTime Mandarin, a resource which helps you bridge the gap to real-world fluency in Mandarin, stay informed about China, and communicate with confidence—all through weekly immersion in real news.