"Workhorse" — Phrase of the Week

The tragic suicide of a 25-year-old trainee doctor highlights the problems with China’s doctor training system

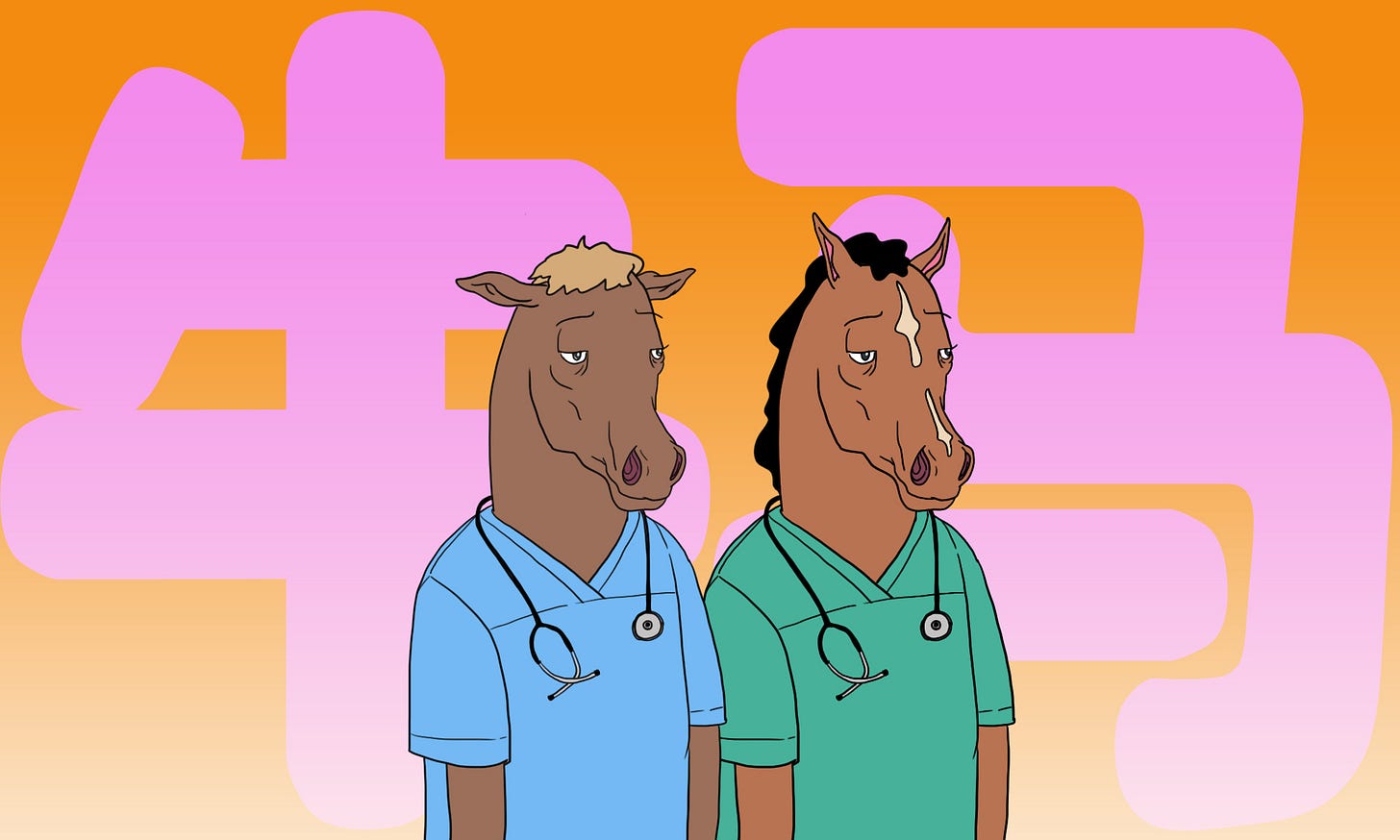

Our phrase of the week is: "workhorse" (牛马 niú mǎ).

Context

In the early hours of February 24, Cáo Lìpíng 曹丽萍, a 25-year-old resident doctor at Hunan Provincial People's Hospital, was found dead in the doctors' duty room.

She took her own life hours before.

Liping was a student in the program for “professional training for resident physicians” (规培医生 guīpéi yīshēng), which has trained over 1.1 million physicians in China since it started in 2014.

Having been on the training program for nearly seven years, Liping was only six months away from completing her training and becoming a fully qualified doctor.

She had an intensive working schedule.

According to chat records made public by her family, Liping had repeatedly asked her supervising doctor for time-off in the weeks leading up to her suicide. She was experiencing rapid heartbeat and high blood pressure.

Those requests for time off were refused.

Her death has sparked debate in China about the treatment of trainee doctors. They are expected to work long hours for very little pay, as one social media post from another trainee doctor who knew Cao Liping suggests:

I thought the main purpose of residency training was to learn how to apply theory into clinical practice.

Turns out, it's to be a free workhorse for the department.

我以为规培的主要目的是学习,是把知识和临床结合,原来是给科室当免费的牛马。

Wǒ yǐwéi guīpéi de zhǔyào mùdì shì xuéxí, shìbǎ zhīshi hé línchuáng jiéhé. Yuánlái shì gěi kēshì dāng miǎnfèi de niúmǎ.

And with that we have our Sinica Phrase of the Week.

What it means

“Workhorse” directly translates as “cattle” (牛 niú) and “horses” (马 mǎ), sometimes translated as “beast of burden”.

It’s an internet slang term, used metaphorically to describe people who are made to work hard for little money, and with little hope of improving their circumstances.

The most likely origins of this phrase is the four-character idiom, “to be a cow and a horse” (做牛做马 zuò niú zuò mǎ), meaning “to work hard, endure a hard life, for little reward”.

This idiom is common in spoken Chinese, often used in the context of parent-child relationship, where parents willingly sacrifice everything for the next generation.

In modern Chinese, and especially since 2021, the two-character phrase “cattle and horses” (牛马 niú mǎ) has become a common way to describe people whose lives are dominated by low paid, unrewarding work.

“Social livestock” (社畜 shèchù) is another common phrase with a similar self-deprecating meaning, and uses the same metaphor as “cattle and horses” in Chinese. And both phrases could also be translated as “working people” (打工人 dǎgōng rén).

The tragic death of Cao Liping is just one example of the need for China’s health system to be reformed.

A system, according to accounts of people who have been through it, which treats trainee doctors just like livestock, squeezing as much out of them as possible, like expendable human resources, or “huminerals” (人矿 rénkuàng), to use another popular internet phrase of 2023 explained by eminent Sinologist, Geremie R. Barmé.

So we translate this Phrase of the Week as “underpaid and overworked beast of burden”.

Andrew Methven is the author of RealTime Mandarin, a resource to helping you learn contemporary Chinese in context, maintain and improve your Mandarin skills, and stay on top of the latest language trends in China.

Read more about how this story is being discussed in the Chinese media in this week’s RealTime Mandarin.