For short-term investors, the 2026 China story will be familiar: world-class innovation by tech and health care entrepreneurs. For investors with a long-term horizon, this year’s story will be more interesting, as Beijing’s policy pendulum swings towards supporting the return of the Chinese consumer and away from a focus on regulatory control. This will require patience, as Xi Jinping is taking an incremental approach to fixing the key obstacle to stronger consumption: a very weak housing market.

The 2025 China Macro Story Was Uninspiring . . .

Last year’s China macro data was uninspiring. For example, nominal retail sales rose by 4% YoY during the first 11 months of 2025, compared to 8% growth during pre-COVID, pre-regulatory crackdown 2019. Fixed asset investment fell 2.6% during the first 11 months of last year, vs. a 5.2% rise in 2019.

. . . But It Wasn’t A Collapse

The pace of economic growth was disappointing, but — despite what you may have read in the media — it was far from a collapse. The IMF, in its October update, forecast that China’s GDP growth rate in 2025 and 2026 would be the world’s second-fastest among major economies, surpassed only by India. This year, the IMF expects China’s economy to grow twice as fast as the U.S. The Fund’s Managing Director said in December that “China is contributing about 30% to global growth” and “over the next couple of years, very likely there would be around 30% contribution to global growth.”

And while the Chinese government’s macro data collection capabilities clearly can be improved, economists at the International Finance Division of the Federal Reserve Board in Washington concluded that “recent GDP growth figures, which have been in line with the stated target, appear to align closely with broader Chinese economic indicators and do not appear to be overstated.”

Consumer Confidence Is Weak . . .

Weak confidence among Chinese consumers and entrepreneurs is a key problem. The government’s own consumer confidence index fell sharply, from 113 to 87, during the 2022 Shanghai COVID lockdown. By November of last year, the most recent data available, the index had improved only marginally, to 90.3. (It is noteworthy that the Chinese government continues to publish this confidence data set monthly, despite its weakness.)

. . . But Chinese Investor Confidence Is Strong

In May 2022, JPMorgan’s tech analysts shook the global finance community by declaring that China was “uninvestable.” Last month, however, the bank’s head of global equity strategy said they had “fully flipped” to an overweight position on China.

That reversal by JPMorgan trailed strong China equities performance. In 2025, the MSCI China index rose by about 28% in dollar terms, handily beating the MSCI USA, which was up about 17%. The Shanghai Composite index was up a bit more than the S&P 500. The ChiNext tech stock index was up about 50% while the Nasdaq composite rose about 20%.

Why Is China’s Growth Uninspiring? Bad Policy Choices

When I first visited China as a student in 1980, it was very poor, with a per capita GDP less than that of Afghanistan and Haiti. Now it is the world’s second-largest economy, with a thriving middle class. This came about because the Chinese people are incredibly resilient, and because the Communist Party has been increasingly pragmatic about economics. The Party’s economic policy pendulum moved steadily towards support of entrepreneurs and markets. The private-sector share of urban employment has risen from approximately 0% when I was an American diplomat in Guangzhou in 1985 to approximately 90% today.

This pragmatism continued through the first seven years of Xi Jinping’s tenure as Party chief, but was interrupted in 2020 as he sent the policy pendulum in reverse, towards regulatory control. That began with misguided efforts to deal with real structural problems in the housing market. The “three red lines” policy of 2020 crashed new home sales and starts, leading to job losses and falling residential prices.

Government policy overall became increasingly focused on regulatory control, and efforts to fix problems only compounded them. A wide range of sectors were targeted, including internet platforms, online gaming, education, health care, electronic cigarettes, and coal mining. This weakened confidence among entrepreneurs running the small, private firms responsible for China’s innovation and wealth creation. The growth rate of private investment was 4.7% YoY in 2019, but stalled during 2022-2024 and fell by 5.3% YoY during the first 11 months of 2025.

With most urban Chinese either entrepreneurs or employed by entrepreneurial firms, consumer confidence weakened as well, especially after the government poorly handled the 2022 COVID lockdowns in more than 100 cities.

Sales and hiring slowed. Youth unemployment has been running at 15% or higher since July 2024. Income continued to grow, but at a slower pace, rising 5.2% YoY in real (inflation-adjusted) terms during the first three quarters of last year, down from 6.1% YoY during the same period in 2019.

Why Is China’s Growth Uninspiring? It’s Not About Ideology

It is important to recognize that the economic policy mistakes described above were not driven by an ideological opposition to entrepreneurs. Private firms have continued to thrive since Xi became Party chief in 2012, and have driven all net new job creation. The private sector share of total urban employment has risen from 82% in 2012 to 89% in 2024.

The number of private firms increased by more than fourfold since 2012. In the first half of last year, 4.3 million new private firms were established, an increase of 5% YoY.

Xi is clearly counting on the success of private firms, which account for 90% of China’s high-tech companies and which dominate the industries Xi is promoting: batteries, electric vehicles, and artificial intelligence. Thirteen of the 15 globally significant Chinese battery makers are privately owned; seven of the top 10 electric vehicle makers (by number of units produced) are privately owned; and the eight leading AI startups are privately owned.

Xi Began To Course Correct In September 2024

The policy pendulum started to clearly change course at a September 2024 meeting of the Party’s senior leadership, the Politburo. Xi effectively acknowledged that his emphasis on regulatory control had gone too far, and he began a gradual return to pragmatism. Most importantly, since the fall of 2024, there have not been any new, significant regulatory campaigns announced.

A February 2025 meeting between Xi and some of China’s leading tech entrepreneurs — including Alibaba founder Jack Ma and DeepSeek founder Liang Wenfeng — kicked off renewed political support for the private sector.

After three years of overly aggressive policies, entrepreneurs and consumers have responded cautiously. Retail sales and private investment have remained weak, but the consumer sentiment index has risen from 85.7 in September 2024 to 90.3 in November 2025. The positive equities performance last year was due in large part to the policy changes.

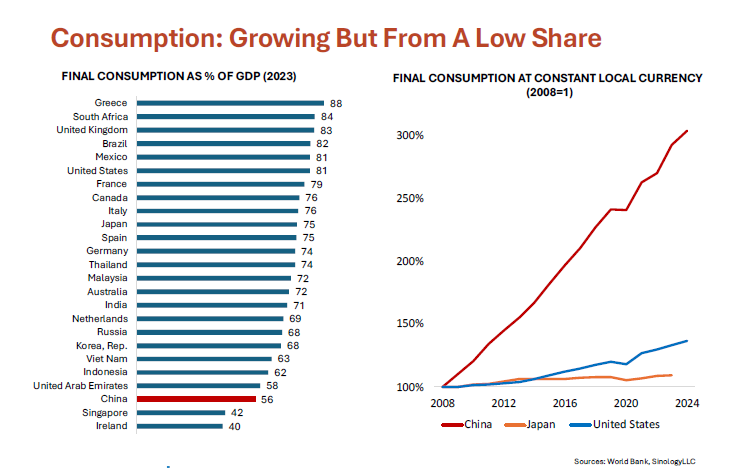

The consumption story has slowly begun to turn around. In 4Q24, final consumption accounted for only 30% of GDP growth, but that share has been rising, to 52% in 1Q and 2Q25, then 57% in 3Q25.

In December 2025 Xi Made Promoting Consumption A Political Goal

Recognizing that he had not yet done enough to rekindle confidence and consumption, Xi went all in on domestic demand in December. He is making clear that he understands that China can no longer rely on exports or investment to drive growth.

In widely publicized statements in China’s media, Xi is signaling that boosting consumption is a top political priority:

“We must accelerate efforts to address the shortcomings in domestic demand, especially consumption, making domestic demand the main driving force and anchor for economic growth.”

Xi is also acknowledging that industrial overcapacity means China cannot return to its old playbook of using investment stimulus to promote economic growth:

“In the past, my country’s production capacity lagged behind, so the focus was on expanding investment and improving production capacity. Now, with overall overcapacity, relying solely on expanding investment to boost growth has limited effect and diminishing marginal utility. While investment can be a significant driver of economic growth in the short term, final consumption is the sustainable engine of economic growth.”

And Xi is not proposing to use exports to boost growth. All of his rhetoric is focused on domestic demand:

“Expanding domestic demand is a strategic move . . . not a temporary measure to cope with financial risks and external shocks.”

Xi speaks about “investing in people,” as opposed to traditional investment in infrastructure and manufacturing, although he hasn’t yet provided details:

“The most fundamental way to expand consumption is to promote employment, improve social security, optimize the income distribution structure, expand the middle-income group.”

Reasons to Be Optimistic that the Chinese Consumer Will Return

The Chinese consumer has been lying flat recently, and while Xi is making boosting consumption a political priority, some people are skeptical of both his commitment and his ability to execute. This skepticism may be due to observers not remembering how strong consumption was earlier in Xi’s tenure, before the series of policy mistakes hit consumer confidence. Prior to the pandemic, consumption was the main engine of China’s economic growth.

In the five years before COVID, real final consumption accounted for 64% of China’s GDP growth, while net exports on average contributed only 1% of growth. (The balance was from investment and inventory changes.)1

Consumption weakened considerably in the next five years, as government policy mistakes (the regulatory crackdowns described earlier, especially on the housing market, and the COVID lockdowns) led to a collapse in confidence, rising unemployment, and slower income growth. Between 2020 and 2025, final consumption on average contributed only 47% of annual GDP growth, allowing the net export share to rise to a 16% contribution.

But there’s no evidence that Xi has been opposed to consumption. From 2012, when Xi became head of the Party, through 2019, consumption growth in China averaged 7.6% vs. 2.1% in the U.S. in real terms.

The collapse in consumer confidence and slower income growth dragged consumption growth down to an average annual pace of 4.8% from 2020 to 2024, but that was still significantly faster than the 2.7% rate in the U.S. during those years.

Consumption is weak in China today, which is why Xi is making boosting consumption a top political priority. But despite the current problems, China remains the world’s second-largest consumer market and the world’s fastest-growing consumer market.

The Biggest Risk: Real Estate

The biggest obstacle to the return of the Chinese consumer, and the reason this is likely to be a lengthy process, is the deep problems in the residential property market. This is a key factor behind weak consumer confidence, but Xi has not revealed any sense of urgency for solving those problems.

The decline in the housing market is stark. In the first 11 months of 2025, new home sales fell 8% YoY on a square meter basis, equal to only 47% of sales in the peak year of 2021.

Residential property prices in China have decreased by about 25% since mid-2021, and are down even more in some smaller cities.

Unlike in the U.S., this has not created a financial crisis, because of high cash downpayment requirements and strict mortgage due diligence processes, but it has had a significant impact on consumer spending.

A 2019 survey by China’s central bank found that housing accounted for almost 70% of assets for urban households. A 2025 study by economists at Bank for International Settlements (BIS), a think tank for global central banks, reported “a significant housing wealth effect” in China’s larger cities (Tiers 1 and 2, accounting for one-third of the total urban population), which “underscores that a considerable portion — over 37% — of China’s consumption is closely linked to the real estate market.”

China’s leadership has acknowledged the problem and pledged to deal with it. The September 2024 Politburo meeting we referenced earlier set a goal of “promoting the stabilization and recovery of the real estate market.” The December 2025 Central Economic Work Conference described the housing market as a key risk and called for “construction of a new model of real estate development.”

Xi, however, has not made this a priority. He has yet to announce (and fund) a detailed plan for stabilizing housing prices, preferring to watch and wait for the market to clear without major government intervention.

This will take time, which is why we expect the return of the Chinese consumer to be a gradual process.

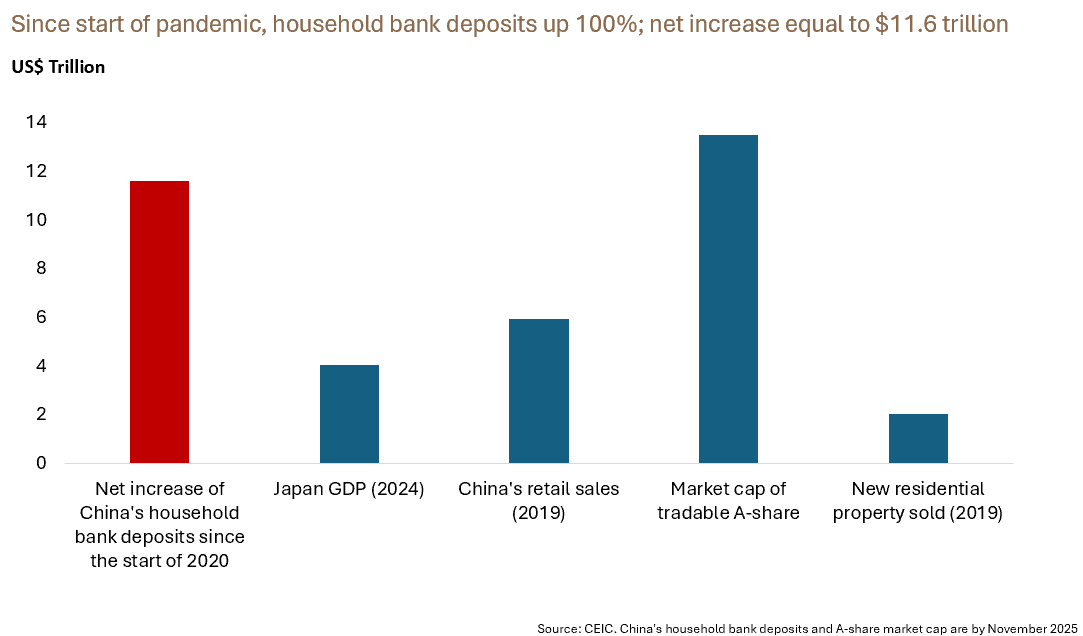

When Confidence Does Return, Consumers Have Cash

Over time, I expect consumer and entrepreneur confidence to return. When confidence does return, it will be supported by the massive increase in family savings since the start of the pandemic and the regulatory crackdown. The net increase in household bank accounts since the start of 2020 is equal to US$11.6 trillion, which is more than double the size of Japan’s 2024 GDP.

This could be significant fuel for a consumer spending rebound, as well as a sustainable recovery in mainland equities, where domestic investors hold more than 95% of the market.

*[Note: A common way to measure GDP is the expenditure approach, which includes final consumption by households, non-profits, and the government; plus investment in capital goods; plus net trade (exports minus imports, or net exports). Final consumption excludes intermediate goods, which are consumed as inputs to produce other goods. In both China and the US, government consumption accounts for about 17% of GDP.]

Confidence destroyed takes time to re-build. China is finding out now regarding the economy; the US will find out later regarding foreign policy. :-)

You commented that it was noteworthy how the consumer confidence index continues to be published despite weakness - how high fidelity is Chinese gov-reported data generally and what’s the track record on withholding bad macro data? My sense is that China macro data has historically tracked in-line with external indicators and data transparency practices have generally not been majorly different from G7 macro reporting, but there is a widespread narrative that Chinese gov has been particularly bad about these and I’m trying to understand where that perception comes from as I think it explains a lot of bearishness around China macro today